From the temporary breakdown of global supply chains to the emptying of once-bustling city streets, COVID-19 hugely changed the way we navigate our urban environments – and not just in the short term.

With the coronavirus set to reshape the urban landscape for decades to come, CGTN Europe takes a deep dive into the powerful potential of disease to mold our metropolises – past, present, and future – in a four-part series about the impact of COVID-19 on cities.

A PANDEMIC-PROOFED FUTURE

If we had to imagine a pandemic-proof megacity – one that could house millions of people without encouraging the spread of a virus – what would it actually look like?

Some might prioritize personal space for pedestrians: perhaps floating 'sky-gardens' – expansive tree-lined boulevards that hover over the commercial ground plane – could break up rush-hour congestion and offer more room for commuters to navigate the cityscape.

Others might suggest ways to provide eco-friendly, socially-distanced transport: bicycle paths might lead cyclists to work from various eco-transport hubs. And for those concerned by streamlining foot-traffic, the city's skyscrapers could be laid out to nudge pedestrians to their destination along one-way ground plans.

Read more: COVID-19 and the city: What does the future hold for urban transit?

The 'Urban Living Room' masterplan for Qianhai in southern China incorporates a floating 'sky-garden' to break up pedestrian congestion. /www.7-t.co.uk

The 'Urban Living Room' masterplan for Qianhai in southern China incorporates a floating 'sky-garden' to break up pedestrian congestion. /www.7-t.co.uk

During a crisis, dreams abound of how we could make our immediate environment safer. But surprisingly enough, such radical thinking could become a reality.

These are all features of the 'Urban Living Room' masterplan for the bustling tech hub of Qianhai in southern China. Designed by British architects Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (RSHP) in 2018, the blueprints are part of widescale plans to overhaul massive areas of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao greater bay area, one of the world's most populous conurbations.

"When working in China, we're always amazed at the amount of space as part of the urban planning," says RSHP partner Ivan Harbour. "I think we just probably don't really understand the density of the place."

In countries where urban populations are growing rapidly and new city-making is in its heyday, managing the concentration of urban populations was already essential; now, COVID-19 has made the issue even more urgent.

Watch: COVID-19 and the city: The future of pandemic-proofed buildings

Highly concentrated cities can improve productivity, shorten commute times and offer better access to private and public services. /Visual China/VCG

Highly concentrated cities can improve productivity, shorten commute times and offer better access to private and public services. /Visual China/VCG

DENSITY

Besides millions of individual lives, COVID-19 has also attacked the very concept of the city. Anything within an urban area that relies on close human proximity – mass transit, medical infrastructure or that backbone of metropolitan culture, the face-to-face economy – has come under question.

For professor Herbert Girardet, cofounder of the Future World Forum and a specialist in sustainable urbanism, "what stares you in the face is that some of the most worrying incidences of the epidemic are in highly built-up areas. Wherever you have relative density you have these types of problems."

Indeed, at the end of May, Londoners were three times more likely to have COVID-19 than citizens in the rest of the UK. But that density can also be what makes a city efficient.

Read more: Mobility, urbanization amplify coronavirus epidemic risk in China

02:59

According to a recent report from London School of Economics (LSE), highly concentrated cities can improve productivity, shorten commute times and offer better access to private and public services. They can also help reduce urban sprawl, one of the great drivers of the climate crisis.

Some high-density cities have fared comparatively well during the crisis. RSHP's Harbour notes that "Hong Kong is one of the densest cities in the world," but thanks to robust infrastructure, strict social measures and new technologies, "it's managing the virus to date – and their living conditions are tiny: these are postage-stamp apartments."

That sort of random bumping that is a fundamental problem in the context of the virus is actually the most vital thing we have to generate answers and ideas

- Ivan Harbour, British architect

Beyond economic value, having highly concentrated populations can also be what makes a city vibrant: "As human beings, we thrive on community and direct interaction," says Harbour.

"That sort of random bumping, that is a fundamental problem in the context of the virus, is actually the most vital thing we have to generate answers and ideas."

The question then for policymakers, architects and urban planners is how to harmonize density with disaggregation – the breaking-up of populations – in a way that still allows for the chance encounters that drive so much of our urban life.

Read more: Why China can achieve largest urbanization in history

Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo proposes to turn the French capital into a bicycle-friendly '15-minute city.' /Alain Jocard /AFP

Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo proposes to turn the French capital into a bicycle-friendly '15-minute city.' /Alain Jocard /AFP

THE '15-MINUTE CITY'

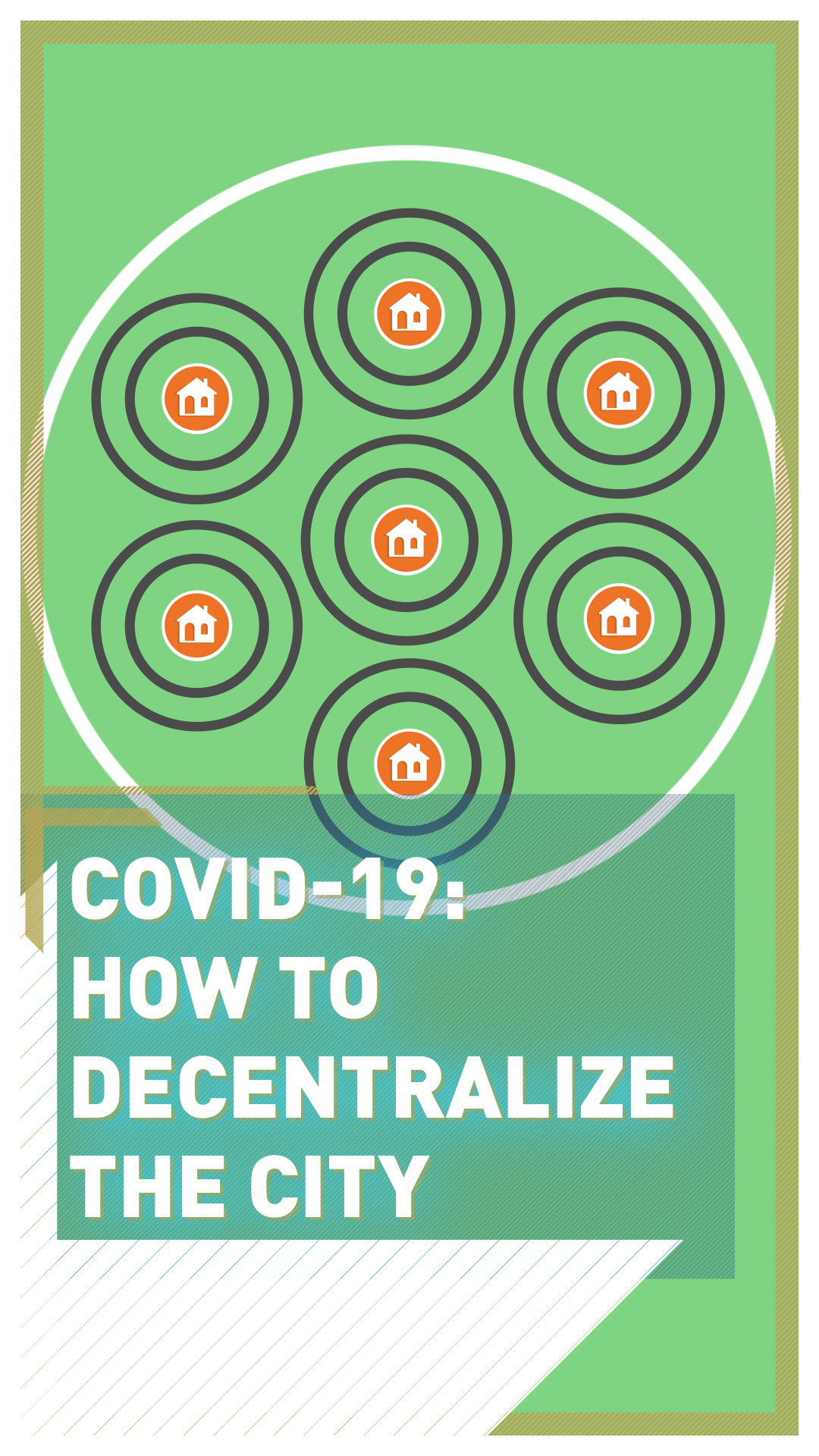

One answer has been to decentralize urban environments. "In a pandemic like this, we see that a centralized city cannot cope with lockdowns," says architect and urbanist specialist Moritz Maria Karl.

We have to break it down into smaller systems and into smaller urban systems. This is a way more resilient way of designing cities

- Moritz Maria Karl, researcher and lecturer at Berlin Technical University

He points to the temporary collapse of centralized supply chains during lockdown and the problem of such large population sets converging in city centers: "We have to break it down into smaller systems and into smaller urban systems. This is a way more resilient way of designing cities."

Such concepts were already gaining traction pre-pandemic in cities like Portland in the U.S. and Melbourne in Australia, but now COVID-19 is giving hyper-localized urban planning fresh propulsion.

The '15-minute city' is a collection of largely self-sufficient neighborhoods where services, jobs, and amenities are within walking and cycling distance. /Micael/Paris en Commun

The '15-minute city' is a collection of largely self-sufficient neighborhoods where services, jobs, and amenities are within walking and cycling distance. /Micael/Paris en Commun

During her re-election campaign, Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo pledged to transform the French capital – already relatively dense, with more than 21,000 residents per square kilometer – into a '15-minute city': a collection of largely self-sufficient neighborhoods in which services, jobs, and amenities are within walking and cycling distance.

Aside from the reclamation of roads for pedestrians and cyclists, Hidalgo's campaign group Paris en Commun are hoping to break up the city's centralized system by encouraging more localized commercial and public hubs.

To achieve this, one suggestion is to have more multi-purpose public buildings; for example, schoolyards would moonlight as nighttime sports facilities, and small-scale retailers and cultural spaces would be encouraged to set up shop in residential areas; dense, but self-sustaining.

Read more: Pedal power in Paris: French capital looks to build on bike boom

DECENTRALIZATION

This is in part, a long overdue response to urban planning preoccupations of the early 20th century.

At the time, Modernist city-makers like Swiss architect Le Corbusier and the designers from the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM) advocated separating the city into completely different functions – a commercial core surrounded by residential areas and manufacturing zones – thus focusing the urban layout on the center.

However, due to urban population growth, ageing city infrastructure and a widespread disenchantment with the idea of high-rise living, such designs have led to highly built-up business districts surrounded by never-ending peripheral urban sprawl.

Le Corbusier's unrealized 1925 model of the Plan Voisin for Paris, which would have reshaped the French capital's urban center. /SiefkinDR /Wikimedia Commons

Le Corbusier's unrealized 1925 model of the Plan Voisin for Paris, which would have reshaped the French capital's urban center. /SiefkinDR /Wikimedia Commons

Not only would Paris's plans for localization help separate populations, reducing the risk of disease transmission; it would also drastically cut commuting times and pollution.

Such 'hyper-proximity' could help to make neighborhoods pandemic-proof while altering the centralized urban planning that has driven much of the city-making in Europe for the last 70 years. And if the pandemic is driving disaggregation at a local level, a similar decentralizing of metropolises could be set to take place on a national scale.

Read more: COVID-19 and the city: How past pandemics have shaped urban landscapes

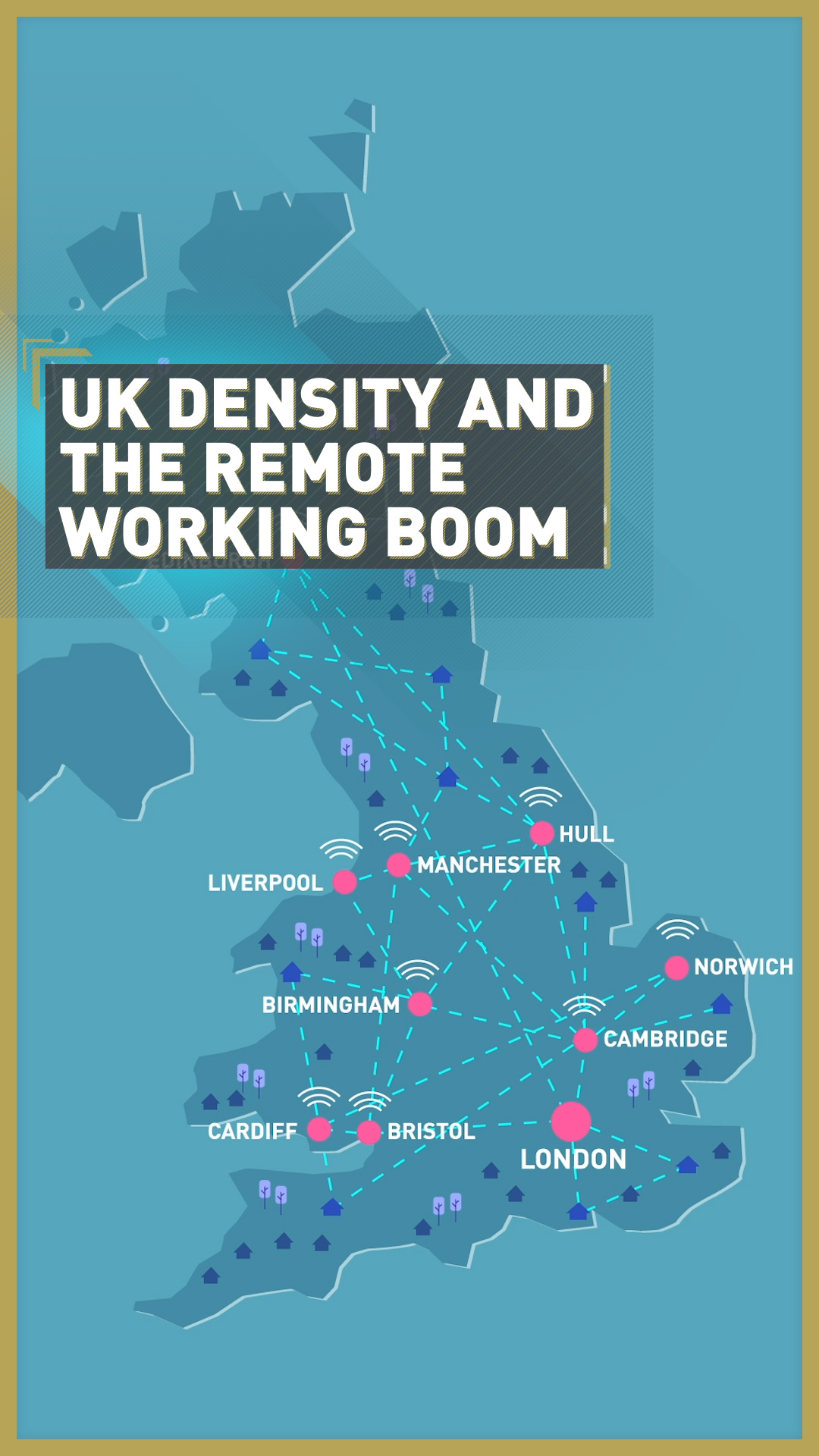

REMOTE WORKING

Since the advent of coronavirus, nearly four out of 10 people in the EU have started to work remotely, according to the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. It's a sea-change in working conditions that could also have major effects on cities.

"It allows for a very different way of life than the one we've taken for granted all these years," says Girardet. "I think certainly these remote working opportunities are coming into their own as never before."

00:30

The remote revolution could allow companies to reduce office space (and its costly overheads) by up to 25 percent, according to Swiss co-working provider Office Lab.

While commercial buildings could be turned into hubs for senior management, employees might only make the commute once or twice a week. But that shift has knock-on effects for domestic spaces.

"It's challenging the way we design apartments," says Moritz Maria Karl. "Flats are usually mono-functional and most don't have the space provided to actually work and live in."

The face-to-face value of stockbrokers chatting in the pubs was not lost on urban planners

- Herbert Girardet, cofounder of the Future World Forum

The phasing out of centralized office culture will affect the informal socializing that drives so many industries. As Girardet puts it, "the face-to-face value of stockbrokers chatting in the pubs was not lost on urban planners over the last 15 years."

Homeworking is already affecting commuter-reliant businesses, large and small. Independent cafes and restaurants have closed, and in May Britain’s biggest sandwich maker Greencore suffered a 40 percent profit drop.

Less immediate but more profound could be the effect on the property market. With homeworking reducing the commute-based need to live near work, significant numbers of people could choose to leave the generally more expensive urban core and move further away, perhaps to the city's periphery, to rent or buy more space for less money.

Read more: COVID-19 and the transition towards remote working

SUBURBANIZATION

The surburban sprawl of many developed-world cities since World War II has caused plenty of problems, but Girardet cites one post-COVID benefit.

"The more you have urban sprawl that is partly suburban and partly denser than the traditional suburb, and the more you enable people to work from those places," he says, "the easier it is to separate and not expose people to the disease vectors which are currently a major problem."

Urban sprawl can cause pollution, flooding, deforestation and heightened temperatures. /Sino View/VSI/VCG

Urban sprawl can cause pollution, flooding, deforestation and heightened temperatures. /Sino View/VSI/VCG

However, increased homeworking may exacerbate those longstanding problems of urban sprawl: the increased threat of pollution and flooding; the endangerment of groundwater reserves; the rising temperatures caused by deforestation and low-density energy demand; and the increasing segregation of communities. These are the products of a city that doesn't limit its territorial growth.

Read more: Has COVID-19 called time on the office?

"When you look in the UK – Bristol, Manchester, Bath, wherever there is a fairly sound economic basis," says Girardet, "you're seeing a lot of expansion of urban suburbs, new housing schemes and so on because of the housing shortage. So the question of where we go from here in terms of home-based working becomes very important."

In the UK maybe it will be positive in terms of a better distribution of density and activity across many cities rather than everything being Londoncentric

- Ivan Harbour, partner at British architectural firm RSHP

SPREADING OUT

However, maybe those who flee the city won't stop at its periphery and will go further, to the countryside or smaller settlements.

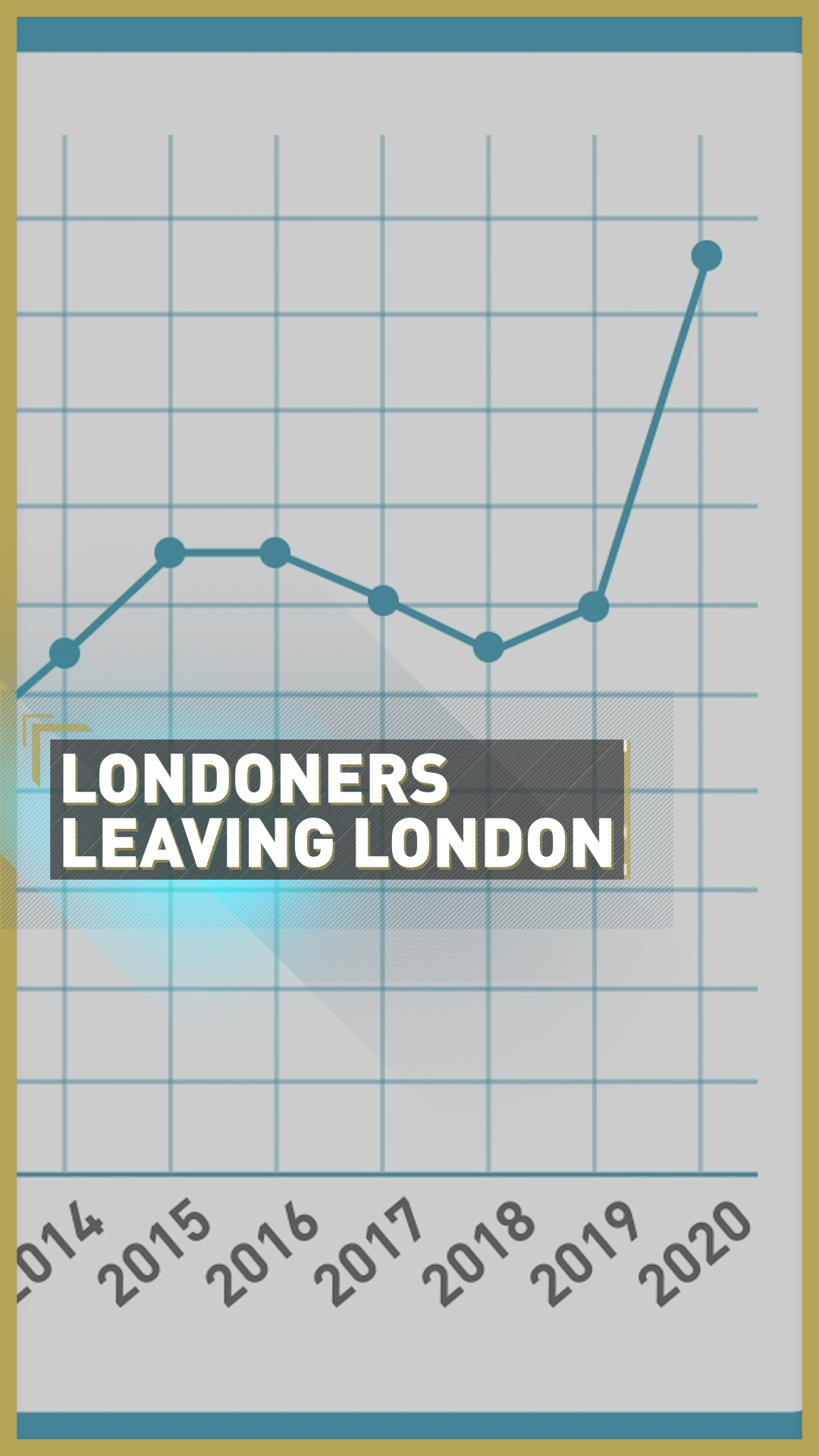

In April, UK letting agent Hamptons reported a year-on-year doubling in the number of clients from London who registered with one of the company's branches outside the capital.

Perhaps the pandemic has inspired a new respect for the bucolic. In a May report by British property firm Savills, 71 percent of younger UK homebuyers said outdoor space and rural locations had become more important to them since COVID-19.

Even prior to the pandemic, figures from the Office for National Statistics showed that 340,500 Londoners moved out of the capital in just one year.

00:18

This points to a potential geographical decentralization of the country and its urban economies. "In the UK, maybe it will be positive in terms of a better distribution of density and activity across many cities rather than everything being Londoncentric," says Harbour.

Read more: Pandemic throws a lifeline to China's electric vehicles makers

However, Harbour sees one major problem with density reduction: "Until there's a viable method of personal transport or a network of public transport which is carbon-neutral, it will have dire consequences for the planet."

The easiest solution to the problems of population growth and the demand for mobility, according to Swiss investment bank UBS, lies in the expansion of our rail networks. The investors are predicting strong growth in the industry over the next decade, particularly in the EU, where growing climate consciousness is necessitating alternatives to gas-guzzling transport methods.

Deloitte predicts that with future cost reductions for manufacturing batteries, electric vehicle sales could go from two million units in 2018 to 21 million in 2030. /Visual China/VCG

Deloitte predicts that with future cost reductions for manufacturing batteries, electric vehicle sales could go from two million units in 2018 to 21 million in 2030. /Visual China/VCG

While remote working may be set to change urban-density patterns in the service economies of Europe, the shift will be less noticeable in many manufacturing-based economies in the global south.

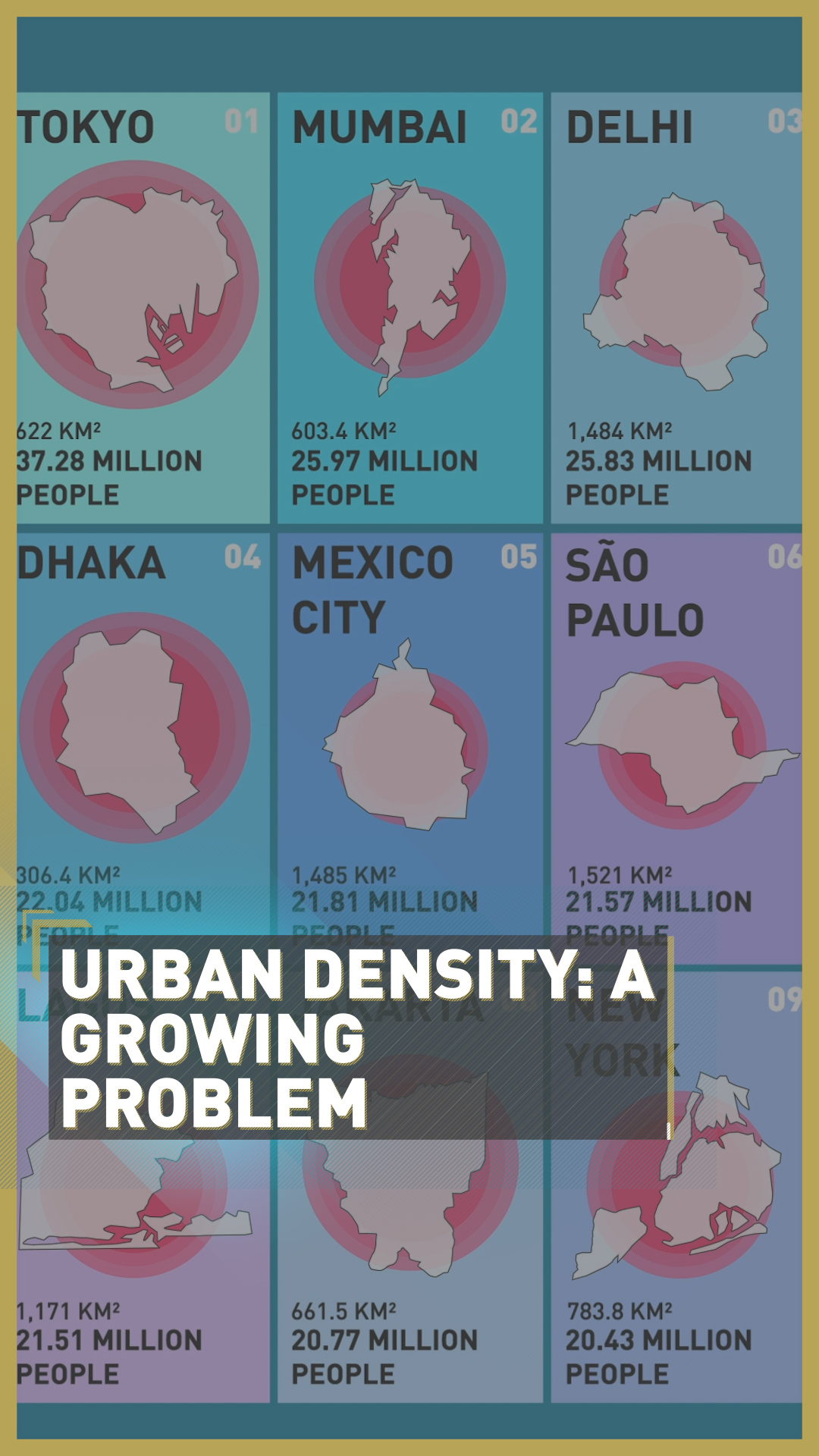

However, the need to rethink urban congestion there is just as urgent, if not more so. With metropolitan populations skyrocketing in many emerging economies, finding an ecologically sustainable way to better distribute density in our fastest-growing cities will be vital.

But luckily, this is where new city-making is in its prime.

Read more: Will the coronavirus pandemic make 'work from home' popular?

MEGALOPOLISES

"When you look at countries like China, that's where the really big cities are being built," says Girardet, who has himself contributed to sustainable urban planning designs in China.

"In Europe, London is the largest city with nine million, but in pockets of China, where you have Guangdong and Shenzen and Hong Kong clustered into an urban region of a 100 million people, it's totally unprecedented."

00:55

Whereas European nations, in their long-ago era of greatest population growth, could afford to offload parts of their populations to colonies, countries in the global south were left to build what Girardet describes as "mega-mega-mega cities."

And the day-to-day consumption patterns of megalopolises with such high populations – Mumbai's 26 million, Dhaka's 22 million, Sao Paulo's 21.5 million – can have a drastic impact on both local and global environments.

New diseases from Ebola to COVID-19 to SARS are a result of the pressures of consumption by cities in territories halfway across the world

- Herbert Girardet, cofounder of the Future World Forum

"The new diseases that we are seeing occurring now – from Ebola to COVID-19 to SARS and so on – are all a result of the pressures of consumption by cities in territories half way across the world," says Girardet.

Demand for meat has skyrocketed in emerging economies in the last few decades, with consumption almost tripling in South East Asia since 2000. The consequent industrial agricultural boom has put increased pressure on ecosystems, heightening the risk of exposure to diseases.

But beyond the pandemics, heightened urban consumption is taking its toll on our ecosystems across the board.

00:36

"We can try to reorganize the way we live in our cities as much as we like," says Girardet, "but unless we get to grips with the ecological footprints of our urban environments, in the end, whether you live in a suburb or newly densely built-up area or a high-rise building – anywhere – ultimately, exposure to disease vectors of the kind that we are seeing becomes unavoidable."

With more than two-thirds of the world population set to live in urban areas by 2050, for emerging economies with large populations, this makes new sustainable urban planning projects all the more urgent.

Read more: Are farming methods causing an increase in viruses like COVID-19?

ECO-CITIES

China is one of the countries trying to get on top of the issue, with more than 280 government-backed plans for "eco-cities" around the country – like the flagship Tianjin Eco-city, nestled at the edge of one of its biggest ports.

With its tree-lined canals, green buildings and plans to go zero-waste, the project offers a glimpse of what local urban planning might look like in the future for countries in the global south.

China's flagship Tianjin Eco-city is nestled at the edge of one of the countries biggest ports and has plans to go zero-waste. /Sino View/VSI/VCG

China's flagship Tianjin Eco-city is nestled at the edge of one of the countries biggest ports and has plans to go zero-waste. /Sino View/VSI/VCG

However, a longer-term solution on a nationwide level is also needed, one which can offset the impact of megalopolises on non-urbanized land while separating their populations into smaller, more ecologically sustainable units.

Watch: China-Singapore ties: Joint efforts made to develop sustainable urbanization

"Certainly now in China there is a conversation going on about intermediate cities," says Girardet. He references the concepts of the 20th-century garden cities. A response to pandemics of the time, these were new health-conscious, mini-satellite settlements, separated from nearby metropolises by sustainable farmland and greenbelts.

"In China, you have the extreme of the village and the megacity on the other," he says, "so it's beginning to be realized that it makes sense to try a sort of halfway-house urban development where you have partially agricultural, partially manufacturing, and partially service-based economies emerging."

The planned Chaluhe agro-city would exist on a mixed economy, connected to neighboring cities by eco-friendly transport links, and surrounded by an agricultural zone of rice paddies to help manage the threat of flooding. /Visual China/VCG

The planned Chaluhe agro-city would exist on a mixed economy, connected to neighboring cities by eco-friendly transport links, and surrounded by an agricultural zone of rice paddies to help manage the threat of flooding. /Visual China/VCG

One such pilot is the Chaluhe "agro-city" in China's northern Jilin province. Equidistant between the region's largest cities, its planned population of 300,000 would exist in a mixed economy, connected to its neighbors by ecologically friendly transport links.

With access to a flexible labor pool, the agro-city would also surround and be surrounded by an agricultural zone of rice paddies to help manage the threat of flooding in the region.

Read more: China-Singapore ties: Joint efforts made to develop sustainable urbanization

A PANDEMIC-POWERED REVOLUTION

With hundreds of new cities in the pipeline in China, and many more throughout the global south, such concepts offer a way to meld the benefits of ecological sustainability, density and disaggregation for nations trying to house their growing populations.

But for Girardet, localized eco-city planning is not enough: "Unless we turn linear systems into circular systems, mimicking nature as best we can, we can't continue developing an urbanizing world without massive penalties like the one we are faced with at the present time."

RSHP's Urban Living Room masterplan for the bustling tech hub of Qianhai in southern China is part of widescale plans to overhaul areas of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao greater bay area, one of the most populated urban areas in the world.

RSHP's Urban Living Room masterplan for the bustling tech hub of Qianhai in southern China is part of widescale plans to overhaul areas of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao greater bay area, one of the most populated urban areas in the world.

Thankfully, pandemics do have the power to drive urban revolutions. They helped sculpt Europe's sewage systems and shaped its Modernist housing estates.

Now, around the world, the current crisis is revolutionizing urban technology, medical infrastructure and the way we navigate the city.

We can't simply take COVID-19 as the only starting point in this discussion

- Herbert Girardet, cofounder of the Future World Forum

Signalling the key ways we can protect and improve the quality of urban life, both the climate crisis and the coronavirus will likely drive urban planning well into the 21st century, having already accelerated a radical rethinking of how we build cities.

"We can't simply take COVID-19 as the only starting point in this discussion," says Girardet. While that may be the case, coronavirus has undeniably altered the conversation, and learning its lessons will be vital to our future in the ever-mutating built environment. Even in the face of pandemics, the city grows.

Video editors/graphics: David Bamford, Natalia Luz, James Sandifer, Omar Abusitta