From the temporary breakdown of global supply chains to the hollowing out of once bustling city streets, COVID-19 has caused a seismic change in the way we navigate our urban environments.

Now, with the coronavirus set to reshape the urban landscape for years to come, CGTN Europe takes a deep dive into the powerful potential of disease to mold our metropolises – past, present, and future – in a four-part series about the impact of COVID-19 on cities.

COVID-19 has brought with it many state-sanctioned directives for how European city-dwellers must navigate their built environment, but one message in particular cut through around the continent as the pandemic accelerated: #StayAtHome.

However, amid a multi-billion-dollar European housing crisis, where modern living conditions can actually accelerate the threat of the novel coronavirus, such advice can sometimes ring hollow.

The pandemic has painfully highlighted the cracks in parts of the urban infrastructure on a continent where people spend on average 90 percent of their time indoors even though nearly one in five Europeans live in overcrowded dwellings.

04:56

The pandemic reinforces what we already always thought architecture should be about - providing inspirational space that is safe, but also crucially, healthy for those that use it.

- Ivan Harbour, architect and partner at Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

"What does resonate unfortunately," says Emily Sargent, senior curator of the Wellcome Collection in London, "is that those who live in substandard housing – those whose homes already represent a risk to health - have been harder hit by these restrictions to stay home."

Indeed, according to the UK's New Policy Institute, Britain's top five most over-crowded areas witnessed 70 percent more coronavirus cases than the five least-crowded at the start of the pandemic.

For the institute's director Peter Kenway, "our models show that even when you allow for the obvious factors, there is still a heightened risk to overcrowded households, especially when you have older people living with younger people."

Read more: COVID-19 to push up UK poverty levels - state aid expert explains why

And with the increased cost of living in many European cities progressively driving people into smaller living spaces, the dangers of overcrowding, poor ventilation and low quality heating are threatening more and more urban inhabitants amid the pandemic.

But conversely, the virus has also seen breathtaking architectural innovation and an urgent reshaping of parts of our built environment, opening a window to the possibilities of pandemic-proofed buildings of the future.

By building on the quiet revolution in health-conscious architecture that has taken place over the last decades, alongside the 21st century breakthroughs in low-cost construction technology, COVID-19 may actually offer a solution to the shortcomings of modern buildings that have helped the spread of the virus.

Read more: COVID-19 and the city: How past pandemics have shaped urban landscapes

For veteran architect Ivan Harbour from Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (RSHP), the firm behind such iconic sites as London's Millennium Dome and 3 World Trade Center in New York, the pandemic "reinforces what we already always thought architecture should be about: providing inspirational space that is safe, but also crucially, healthy for those that use it."

"I'm hoping what will come out of this crisis is recognition that actually these things are fundamental."

Read more: COVID-19 impact on China's property market is limited

CLEAN AIR/GREEN BUILDINGS

RSHP's Lloyds of London building, built in the 1980s, is now considered one of the great architectural achievements of the era. John Lamb / Getty Creative / VCG

RSHP's Lloyds of London building, built in the 1980s, is now considered one of the great architectural achievements of the era. John Lamb / Getty Creative / VCG

I would hope that there will certainly be a better response to the idea of buildings being better serviced in terms of their ventilation and air quality.

- Ivan Harbour, architect and partner at Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

If clean air is one of the keys to beating the pandemic, Ivan Harbour has been helping to revolutionize the ways in which it is incorporated it into workspaces since his work on the iconic Lloyds of London building in the 1980s, now considered one of the great architectural achievements of the era.

Here, Harbour and his colleagues honed the concept of "Inside Out Architecture," taking the systems that usually lie inside a building – elevators, pipes, air conditioning systems, and ventilation ducts – and put them on the outside of the building, mirrored in the their work on the Pompidou center in Paris.

While for Harbour, the Lloyds building was "a practical response to a practical problem" – through their 'Inside Out' design, RSHP got around the City of London's strict building restrictions to give Lloyd's an extra 20 percent net area – its architecture quite literally brought ventilation and air circulation to the forefront of their designs. And today, the issue couldn't be more vital.

Read more: What does an inflatable COVID-19 biosafety lab test look like?

The Centre Pompidou in Paris designed by RSHP was one of the early examples of 'Inside Out' buildings, where the buildings ventilation was literally brought to the forefront of its design. / Visual China / VCG

The Centre Pompidou in Paris designed by RSHP was one of the early examples of 'Inside Out' buildings, where the buildings ventilation was literally brought to the forefront of its design. / Visual China / VCG

According to Harvard Professor Joseph Allen, a specialist in healthy buildings, the majority of structures continue to use cheap filtration systems that catch less than 20 percent of virus-sized airborne particles. One U.S. report estimates that bringing ventilation up to scratch could be as effective in stemming airborne diseases as vaccinating half the building's population.

In the short-term, the quick-fix solution would be to employ portable filtration systems - a market set to boom amid the pandemic. "I would hope that there will certainly be a better response to the idea of buildings being better serviced in terms of their ventilation," says Harbour. However, RSHP's approach to air quality shows how new builds could combat poor-quality in the long-term.

RSHP's Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), one of many commercial sites that make up the International Quarter London, a new business quarter that is being marketed as "the capital of wellbeing" in the British capital. /Hayes Davidson

RSHP's Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), one of many commercial sites that make up the International Quarter London, a new business quarter that is being marketed as "the capital of wellbeing" in the British capital. /Hayes Davidson

I'm hoping that what [the pandemic] does is reinforce what we always felt was right about giving people access to good daylight, good air and access to green space.

- Ivan Harbour, architect and partner at Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

"The scheme that we recently completed for Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is all about full fresh air," says the architect. The building is one of many commercial sites that make up the recently constructed International Quarter London in the East London district of Stratford, a new business area being marketed as "the capital of wellbeing" in the British capital.

The FCA's design uses natural buoyancy, manipulating the force that results from temperature differences between the interior and exterior – regulated by Closed Cavity Facade cladding that monitors the position of the sun and adjusts the blinds accordingly to keep temperatures comfortable - to allow the building to quite literally breathe.

RSHP's Financial Conduct Authority building has the same technologies used in their Lloyds Register of Shipping design (pictured) 20 years ago, but now it can be used in a relatively low cost commercial building. /Google Earth

RSHP's Financial Conduct Authority building has the same technologies used in their Lloyds Register of Shipping design (pictured) 20 years ago, but now it can be used in a relatively low cost commercial building. /Google Earth

This also points to the importance of controlling humidity in a building: respiratory viruses perform poorly when humidity levels are at mid-range, whereas they thrive at low and high levels. With energy efficiency - keeping warm air in - often superseding concerns around humidity and ventilation, smart systems like those used in the FCA building offer a glimpse of how more buildings could incorporate such concerns in the response to diseases like the coronavirus.

"It's got the technologies that we used with Lloyds Register of Shipping building 20 years ago," says Harbour, "but now going into a relatively low cost commercial building." This offers hope for the future of pandemic-proofed commercial construction.

But while there has been a growing trend to incorporate 'wellness' into architecture, with the FCA building commissioned specifically with health in mind, Harbour says that so often architecture fails in this regard: "The only enemy of this is the funding side of building."

Read more: Why are we experiencing an increase in global health crises?

RSHP's Maggie's West London, a support site for cancer patients, has a 'floating roof.' /Stephen Light / RSHP

RSHP's Maggie's West London, a support site for cancer patients, has a 'floating roof.' /Stephen Light / RSHP

I guess if we were to see what might come out of this emergency is there might be more recognition that there isn't one size fits all.

- Ivan Harbour, architect and partner at Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

In spite of this, health-conscious architecture has been a mainstay of RSHP's work, as seen in the leafy gardens and intimate spaces of their Maggie's Centre, in West London, a support site for cancer patients.

By surrounding the building with a fence of trees, nature's very own form of ventilation, Maggie's employs a low-tech solution to combating poor air quality, something that resonates strongly in the current climate. Similarly, its 'floating roof', raised above the structure's walls, allows for natural light and air to stream in through the entire building, emphasizing the idea of our architecture offering a healthy sanctuary in a dense, urban environment.

"I'm hoping that what [COVID-19] does," says Harbour, "is reinforce what we always felt was right about giving people access to good daylight, and good air and access to green space, all those things that we know figure highly in this sort of formalized analysis of wellness."

The versatile floor-plan and spacing of RSHP's Maggie's West London allows for inhabitants to find their own space while still feeling part of the building's community. /Jennifer Goldsmith / RSHP

The versatile floor-plan and spacing of RSHP's Maggie's West London allows for inhabitants to find their own space while still feeling part of the building's community. /Jennifer Goldsmith / RSHP

Maggie's design also harmonizes one of the key problems faced so far during the pandemic; the human desire for what Harbour calls 'random bumping' - the social side of architecture - and the importance of being able to find private space.

Its mixed floor-plan - a warren of outdoor vistas, small sitting rooms and winding corridors leading to an open community hub at the heart of the building - allows for people to find their own space while still feeling part of the building's community. With the concept of "the smallest building with the most corners," this is one of the balancing acts that would make architecture feel both warm and safe in the face of disease.

Read more: Chinese architect Dong Gong on building spaces that speak and solace

"If you think of space that you enjoy, the really exciting spaces, they tend to be quite intimate," Harbour says, pointing to the importance of mixing up the partition of space. "All these things, I think, are really part of a really broad set of criteria that allow us all to thrive and find our own way of thriving in any environment."

The importance of this has become abundantly clear to many during lockdown. "There might be more recognition that there isn't one size fits all," says Harbour. "Actually we need to create architecture that allows people to do lots of things in lots of different ways."

00:13

One way that such health-conscious design features could become easily applied, not just to specialized or commercial buildings, but to residential housing, is through the recent developments in building information modeling, more commonly known as BIM.

In basic terms, BIM is an intelligent 3D model-based process that allows designers to consider the full lifecycle of a construction project. It incorporates real-life materials - their geometry, characteristics and cost - into the design so architects can trouble-shoot and optimize their building plans.

It also makes it far easier to adjust and update designs 'on-the-fly' than it is with traditional hand-drawn blueprints, because all of the associated design documentation can be automatically synchronized with a click of a mouse. This allows architects to be flexible while pulling up and juggling dense datasets at speed, while drastically cutting construction costs and increasing the speed of the design process.

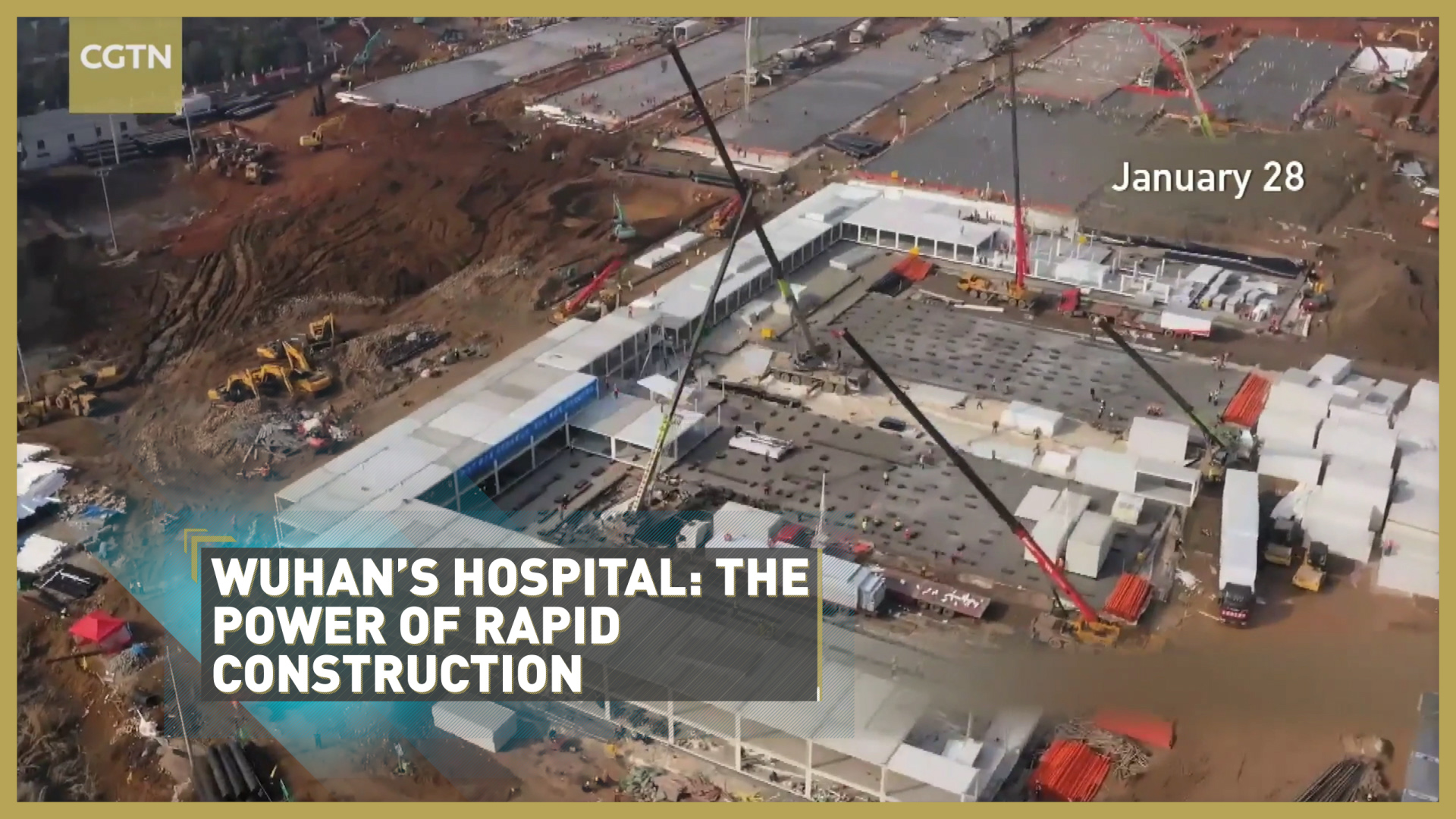

Watch: Demystifying the hospital built in 10 days

Architectural firm BDP used BIM modelling to repurpose Manchester's Central Convention Complex, a 19th century former train station, into one of the UK's temporary Nightingale COVID-19 hospitals at breathtaking speeds. /Jon Super / AP

Architectural firm BDP used BIM modelling to repurpose Manchester's Central Convention Complex, a 19th century former train station, into one of the UK's temporary Nightingale COVID-19 hospitals at breathtaking speeds. /Jon Super / AP

BIM models were used to design the majority of the groundbreaking emergency coronavirus treatment centers during the early stages of the crisis, including the yardstick for such projects, Huoshenshan hospital in China's Wuhan, famously built in just ten days.

In the UK, BDP - the company that helped repurpose Manchester's Central Convention Complex, a 19th century former train station, and the London ExCel center into temporary coronavirus Nightingale hospitals - was able to start construction on the same day they put pen to paper.

Through such flexible technology, BDP was even able to adapt the component system usually used to make exhibition stands at London's ExCel center to build the Nightingale's panel cladding systems that form the hospitals' service corridors and bed-heads.

Watch: The 'psychological PPE' and support developed for staff at the UK's Nightingale Hospital

BDP's instruction manual on how to find a site, design, and build a COVID-19 hospital /BDP

BDP's instruction manual on how to find a site, design, and build a COVID-19 hospital /BDP

The process was further streamlined with what is called 'modular offsite construction' – essentially the hyper-precise 3D digitalized version of ready-for-assembly 'prefab' structures that were so popular in the post-war era. Emphasizing the flat-pack approach, BDP even produced an IKEA-style four-step instruction manual based on their BIM design so similar structures could be quickly erected at future outbreak-hotspots.

Having driven the erection of medical infrastructure at the outset of the pandemic, now these technologies and designs have the potential to be turned to other areas of the built environment.

RSHP were the architectural firm behind the futurist European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France. / RSHP

RSHP were the architectural firm behind the futurist European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France. / RSHP

One trend that has characterized the response to COVID-19 and is set to flourish post-pandemic is the retrofitting of buildings. At a low level, we are already seeing existing structures repurposed to the demands of the virus; one-way walking systems in train stations like London's Kings Cross; the ubiquitous use of plastic dividers at supermarket counters across Europe.

But recent advances in 'Smart Building' technology signal a further development, from the potential introduction of voice-operated lifts to the installation of AI monitors that can trace a building's energy efficiency, its use of space, and employee footfall in real time.

Read more: China's first 5G smart construction site

If privacy concerns are properly addressed, for commercial sites, this could mean real-time retrofitting in the face of disease: by analyzing the mass-movement inside a workplace, smart buildings can be used to flag high-contact areas or produce recommendations for how to reconfigure floor plans for safer office foot traffic.

But perhaps the more innovative concept of completely repurposing a building could help answer the housing crisis - with more than 600,000 buildings out-of-use in the UK alone and a dwindling demand for office space amid the remote-working revolution, many structures across Europe could be retrofitted for residential needs.

We should be building buildings that are more durable - the idea that they’re only designed for 60 years and maybe get pulled down after 30 is not really a sustainable future.

- Ivan Harbour, architect and partner at Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

The only real problem is money. "The way that residential buildings and commercial buildings are funded are completely different," says Harbour: "The funding models for buildings don't work that way and that's one of the big conundrums."

However, it does reinforce the idea that buildings of the future have to be far more flexible if they are to be adjusted to the demands of the era, whether it's making a structure resilient in the face of a pandemic or adapting it to a shift in lifestyles and technology.

"The most interesting buildings are those without a specific function that actually could incorporate a lot of different functions," says Moritz Maria Karl, an architect and researcher at the Berlin Institute of Technology, who touts flexible mixed-use buildings - part-residential, part-commercial - as the types of structures that need to flourish in the future.

Read more: UK climate change report: Six key points

RSHP's PLACE / Ladywell in London. /Mark Gorton/RSHP

RSHP's PLACE / Ladywell in London. /Mark Gorton/RSHP

For commercial sites this means making easily adaptable, but long-lasting structures. "I think its has to be more flexible for the future," says Harbour. "We should be making buildings that are more durable - the idea that they're only designed for 60 years and maybe get pulled down after 30 is not really a sustainable future."

But in the short-term, the flexibility of modular offsite construction, used so effectively in the Nightingale hospitals, could be an answer to providing low-cost, quality housing that can be adapted to the needs of its inhabitants.

"It's certainly something which will have a profound effect on construction," says Habour, pointing to the success of RSHP's modular designs for their Y:Cube Housing units and PLACE / Ladywell, both situated in London. They are both cheap, health-conscious residential buildings that can be mass-produced and deployed anywhere for those in need of temporary housing.

Whether this pandemic will be the moment that governments and property markets consider investing in architecture capable of protecting the majority of people from disease, is yet to be seen.

The veteran architect Harbour sees a clear message from recent events: "I think this crisis really reinforces what we already always thought architecture should be about - it should be for people."

Video editor: Natalia Luz