From the temporary breakdown of global supply chains to the hollowing out of once bustling city streets, COVID-19 has caused a seismic change in the way we navigate our urban environments.

Now, with the coronavirus set to reshape the urban landscape for years to come, CGTN Europe takes a deep dive into the powerful potential of disease to mold our metropolises – past, present, and future – in a four-part series about the impact of COVID-19 on cities.

01:44

Health concerns have always steered urban planning and the design of cities.

- Moritz Maria Karl, architect and researcher at Berlin’s Technical University

Victoria Embankment, a two-kilometer stretch of lush gardens and spacious boulevards that runs along the River Thames, is today what might be considered archetypal London. But like so many cityscapes we take for granted, it is a direct result of how London's urban make-up was rewritten to fend off the threat of disease.

In Britain's capital in the 1850s, the deadly outbreaks of cholera that killed tens of thousands of people – long associated with the stench of untreated human waste and industrial fumes choking the city – demanded direct urban intervention. And London's response was to overhaul the city's sewerage system.

Joseph Bazalgette was charged with overseeing the conversion of vast areas of the Thames's marshland into paved walkways, covering pipelines that could take wastewater safely downstream and away from drinking supplies.

An representation from 'The Illustrated London News' in 1865 of the construction of Victoria Embankment in London, England. /Wikimedia Commons

An representation from 'The Illustrated London News' in 1865 of the construction of Victoria Embankment in London, England. /Wikimedia Commons

Unprecedented at the time, to the cost of £1,250,000 (around $191,700,000 today), this marvel of civil engineering drastically cut the rate of contraction of waterborne diseases, but it went further, ushering in a new architectural phase for the city.

The embankment, mirrored by similar sewerage modernization projects in Paris and Berlin in the late 1800s, allowed for the expansion of vast self-described imperial promenades and grand public parks that have come to define many modern-day European capitals.

A cross-section of the Victoria Embankment on the north side of the River Thames in London from 'The Illustrated London News' in 1867. / Wikimedia Commons

A cross-section of the Victoria Embankment on the north side of the River Thames in London from 'The Illustrated London News' in 1867. / Wikimedia Commons

While COVID-19's impact on urban landscapes may feel unprecedented, the reality is that modern-day cities are in part the direct result of history's pandemics. By limiting the spread of waterborne diseases through urban design, Victorian urban planners laid the groundwork for the European cities of today.

For Moritz Maria Karl, an architect and researcher at Berlin's Technical University, "all of this happened to improve people's basic living conditions, to limit the spread of diseases. Health concerns have always steered urban planning and the design of cities."

Read more: Exclusive: Brazilian researchers on discovery of COVID-19 virus in November sewage

The pandemics of the 19th century that prompted London's overhaul of its sewerage system allowed for the expansion of self-described imperial promenades and grand public parks along the Victoria Embankment. /Michal Bednarek / VCG

The pandemics of the 19th century that prompted London's overhaul of its sewerage system allowed for the expansion of self-described imperial promenades and grand public parks along the Victoria Embankment. /Michal Bednarek / VCG

Artist Gustave Dore's illustrated record of the 'shadows and sunlight' of the squalid living conditions in Victorian London, which would later be published as 'London: a pilgrimage' in 1872. / Wellcome Images

Artist Gustave Dore's illustrated record of the 'shadows and sunlight' of the squalid living conditions in Victorian London, which would later be published as 'London: a pilgrimage' in 1872. / Wellcome Images

Of course, the entangled relationship between the architectural body and the human body have endured much longer than this – but the 19th century is when the city becomes the real focus of infectious disease

- Emily Sargent, senior curator at London's Wellcome Collection

In fact, architectural responses to diseases that proliferated in the squalid conditions of Britain's high-density Victorian slums would continue to drive Western urbanism throughout the next century.

While cholera was made almost extinct in London by the 1870s thanks to projects such as the Thames Embankment, airborne diseases including tuberculosis were still rife throughout Britain well into the 1950s, their spread closely linked to the millions of laborers being packed in to newly industrialized Victorian megacities.

"The 19th century is when the city becomes the real focus of infectious disease," says Emily Sargent, senior curator at London's Wellcome Collection and the curator of its Living with Buildings exhibition: "For many people living in any industrial center, whether it be London or Bradford or Glasgow, the risk of your home making you ill was very significant indeed."

Read more: Containment or contagion? What methods have worked against COVID-19

A wood engraving from 1850 showing cramped and squalid housing conditions in the UK.

A wood engraving from 1850 showing cramped and squalid housing conditions in the UK.

This was at a time when unsanitary living conditions in the warrens of back-to-back workhouses, where people often slept six to a room, helped lower the average age of death in areas such as Manchester and Liverpool to 15.

"Poor sanitation, overcrowding, poor ventilation all contributed, and inevitably the most serious cases were among the working poor of these newly industrialized centers."

According to Sargant, these "appalling conditions" inspired architects, city planners, and 19th-century philanthropic factory owners to design new utopian communities that prioritized health through open space and green settlements, many of which continue to shape our cities today.

Read more: Sacrifice, graft and gratitude: How we cared for the sick

The Garden City Concept by Ebenezer Howard, 1902, originally published in 'Garden Cities of tomorrow'. / Wikimedia Commons

The Garden City Concept by Ebenezer Howard, 1902, originally published in 'Garden Cities of tomorrow'. / Wikimedia Commons

Late 19th-century examples of these ideal settlements were Saltaire in northern England and Cadbury's Bournville just outside Birmingham. There, factories and their were workers were relocated to new leafy suburbias where laborers were thought to be better protected from the respiratory diseases spreading in the city.

Middle-class equivalents also started to pop up: "Bedford Park for example, near Chiswick," says Sargant, "marketed itself proudly as 'The Healthiest Place in the World' alongside images of expansive gardens and high surrounding walls, offering the appearance at least of protection from the danger of the city beyond."

These ideal settlements, direct responses to the spread of urban disease, became the inspiration for the Garden City movement that would go on to revolutionize modern city planning.

Watch: China focuses on urban and rural environment improvement

An early example of the City Gardens movement was Welwyn Garden City, founded by Ebenezer Howard on the outskirts of London in 1920. /Garden City Collection

An early example of the City Gardens movement was Welwyn Garden City, founded by Ebenezer Howard on the outskirts of London in 1920. /Garden City Collection

Conceptualized by urban planner Ebenezer Howard at the turn of the 20th century, garden cities were designed to house 10,000 to 30,000 people and hold their own industry and rural belt in an attempt to blend the benefits of the city and the country.

This allowed satellite cities to be self-sustainable and resilient against ruptures in the supply chain caused by disease, allowing for local agriculture to feed its residents with minimal transport costs, all the while offering inhabitants respite from overcrowding and city squalor.

One early example was Welwyn Garden City, founded by Howard on the outskirts of London in 1920, its tree-lined boulevards and leafy vistas later becoming the home of breakfast cereal company Shredded Wheat.

New settlements of the 19th century, such as the Australian capital of Canberra - designed by Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin in 1913 - were heavily indebted to the garden city concept. /Southern Lightscapes-Australia / Getty Creative / VCG

New settlements of the 19th century, such as the Australian capital of Canberra - designed by Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin in 1913 - were heavily indebted to the garden city concept. /Southern Lightscapes-Australia / Getty Creative / VCG

So popular were Howard's ideas during the first half of the 20th century that they produced 28 garden cities in the UK alone, spreading across the globe to the rest of Europe, North America, and Asia. New settlements of the time such as New Delhi in India, the Australian capital of Canberra, and the leafy suburbia of Kowloon Tong in Hong Kong, are all indebted to the garden city concept.

The original function of many of these garden cities has since become defunct in part due to Western deindustrialization, mass spikes in population and urban sprawl. According to Sargent: "Howard recognized that it wasn't enough to move people out to the country for their health – there had to be jobs, fair wages and some form of entertainment."

Some of these qualities are often in short supply today outside megacities, helping to push the garden city out of fashion in the late 20th century. However, with the increased threat of pandemics such as COVID-19, the focus on supply-chain resilience and maximizing public health could very well prompt a renaissance of designs that echo the garden city concept in emerging economies such as India and China.

But that's only if their shortcomings can be remedied.

Read more: Sewage could be the 'canary in the coal mine' for COVID-19 second wave

London's Balfron Tower block, with its brutalist 'streets in the sky,' was designed on modernist principles that attempted to stave off the ill health of new megacities by creating light, easily ventilated, and egalitarian community settlements. /Cianboy / Wikimedia Commons

London's Balfron Tower block, with its brutalist 'streets in the sky,' was designed on modernist principles that attempted to stave off the ill health of new megacities by creating light, easily ventilated, and egalitarian community settlements. /Cianboy / Wikimedia Commons

Hygiene and moral health depend on the layout of cities. Without hygiene and moral health, the social cell becomes atrophied

- Le Corbusier, pioneering modernist architect and urban planner (1928)

Sadly, the failings of yesteryear's utopias are not only reserved for urban planning. The same can be said of the remnants of Europe's often crumbling 20th-century tower blocks and neglected estates, now synonymous with poor health and living conditions. However, just like the garden cities, their erection was driven by the desire to minimize the threat of disease.

Modernist architecture from the 1920s to the 1970s – characterized by functionalism, airy, egalitarian spaces, and reinforced concrete – was inspired by the advent of new technologies and became the main driving force behind European city building and social housing of the past century.

"The pursuit of healthy, hygienic modern spaces was a key factor in the 20th century surge in social housing," says Wellcome's Sargant. "A sort of architectural manifestation of the welfare state with provision for housing for the elderly and the young, as well as social and green spaces."

Watch: How does COVID-19 compare with previous outbreaks?

The residential housing block 'Unite d' Habitation' in Marseille, designed by the godfather of modernism French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier, opened up the possibility of allowing laborer families affordable, well-lit flats with balconies and green communal spaces to better handle respiratory diseases. /Rudiger Ingartner/Image Broker/VCG

The residential housing block 'Unite d' Habitation' in Marseille, designed by the godfather of modernism French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier, opened up the possibility of allowing laborer families affordable, well-lit flats with balconies and green communal spaces to better handle respiratory diseases. /Rudiger Ingartner/Image Broker/VCG

Pablosievert / Wikimedia Commons

Pablosievert / Wikimedia Commons

Rudiger Ingartner / Image Broker / VCG

Rudiger Ingartner / Image Broker / VCG

Jordan Banks / Robert Harding / VCG

Jordan Banks / Robert Harding / VCG

Rudiger Ingartner / Image Broker / VCG

Rudiger Ingartner / Image Broker / VCG

Karmakolle / Wikimedia commons

Karmakolle / Wikimedia commons

Much of our cityscapes today, be it London's Balfron Tower block, with its brutalist "streets in the sky," or the vast socialist housing estates of Central and Eastern Europe, were designed upon modernist principles that attempted to stave off the ill health of new megacities by creating spacious and egalitarian community settlements.

Early modernist buildings, such as the Marseille residential housing block "Unite d' Habitation," designed by the godfather of modernism French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier, "were very much concerned with people being exposed much more to gloomy, dark spaces," says Herbert Girardet, cofounder of the Future World Forum and a specialist in sustainable urbanism.

The pursuit of healthy, hygienic modern spaces was a key factor in the 20th century surge in social housing – a sort of architectural manifestation of the welfare state

- Emily Sargent, senior curator at London's Wellcome Collection

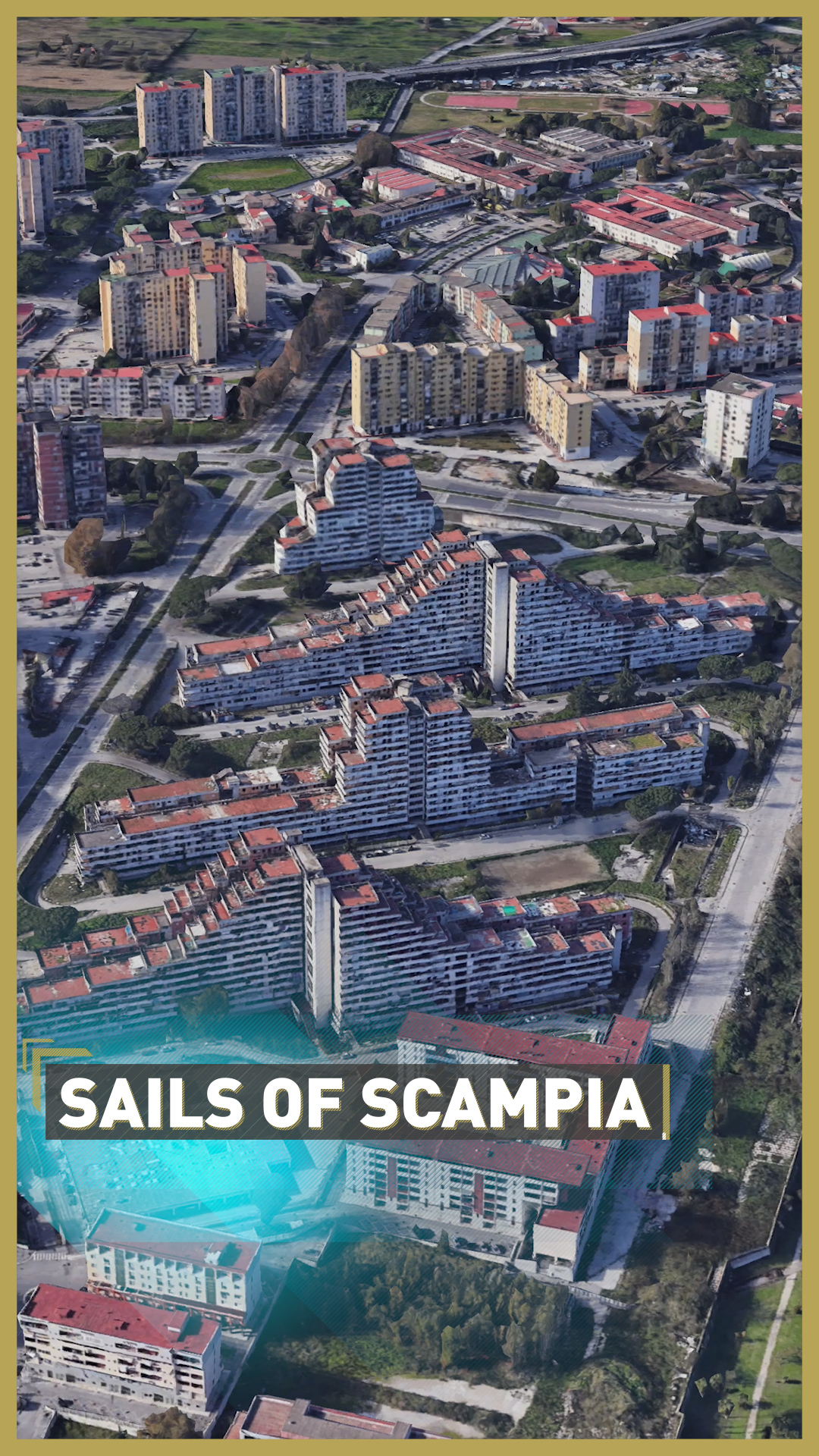

Naples' modernist 'Sails of Scampia' housing project of the 1960s was an attempt to reduce the interior apartment to a bare minimum.

/beeandbee / Getty Creative / VCG

Naples' modernist 'Sails of Scampia' housing project of the 1960s was an attempt to reduce the interior apartment to a bare minimum.

/beeandbee / Getty Creative / VCG

At the time, a lack of sunlight, ventilation, and personal space were seen to be directly linked to the spread of tuberculosis. Le Corbusier's designs, along with those of his European counterparts, opened up the possibility of allowing laborer families affordable, well-lit flats with balconies and green communal spaces to better handle respiratory diseases.

Writing in 1928, Le Corbusier stated: "Hygiene and moral health depend on the layout of cities. Without hygiene and moral health, the social cell becomes atrophied."

In fact, with the threat of some respiratory diseases in Europe waning in the 1960s, many post-war modernist sites didn't have the same health focuses as their precursors.

00:30

"We all know now that despite these good intentions, that many of these spaces have not stood the test of time," says Sargent, pointing to their lack of maintenance and our changing lifestyles.

The infamous "Sails of Scampia" housing project of the 1960s in Naples, Italy – up until the recent destruction of many of its buildings, the home of the Camorra crime family – was an attempt to reduce the interior apartment to a bare minimum, pushing people outside and encouraging them to mingle in its tight Neapolitan "alleyways."

With the progressive departure from the health concerns of the early 20th century, the knock-on effect of unmaintained housing estates, tiny living spaces and cramped corridors, can be seen as one of the reasons why some urban developments from the 1960s onwards have been so effective in allowing the spread of COVID-19.

As Sargent says: "Something that looking back to previous public health emergencies shows us is how quickly we forget."

Video editor: Steve Chappell