From the temporary breakdown of global supply chains to the emptying of once-bustling city streets, COVID-19 has caused a seismic change in the way we navigate our urban environments.

Now, with the coronavirus set to reshape the urban landscape for years to come, CGTN Europe takes a deep dive into the powerful potential of disease to mold our metropolises – past, present, and future – in a four-part series about the impact of COVID-19 on cities.

In the middle of April, at 8:30 a.m. the towering gothic hall of London's St Pancras railway station was virtually empty. Shops in archways lining the concourse were closed and the sound of pigeons gently cooing in the rafters was clearly audible far below.

"It was an absolute ghost town," said Cedric, a customer service assistant at the station. "There were only one or two people walking around. We were still here, the trains were still running, but the station was empty."

Like other cities, traffic on London's public transport system has been building for years, with operators trying to cope by adding longer trains and more services. Still, the carriages were often bursting at the seams. But now, with COVID-19 emptying transport hubs and rewriting the way we navigate the city, the future of urban transit has been turned on its head.

Read more: COVID-19 and the city: The future of pandemic-proofed buildings

02:54

The COVID-19 pandemic makes everyone question what their real needs are or what kind of basic infrastructure we need in a city

- Moritz Maria Karl, architect and researcher at the Berlin Institute of Technology

At the height of the pandemic, traffic volumes in major European cities were reduced by between 70 and 85 percent, according to sat-nav company TomTom, with public transport use dropping by around 75 percent. And although there has been a recent uptick in commuting, social-distancing rules continue to radically decrease mass-transit capacity in major European cities.

Even as we come out of lockdowns, in countries such as the Netherlands the 1.5-meter rule is reducing capacity on the metro, trams, buses and trains capacity to around a quarter of pre-pandemic levels, according to consulting company McKinsey. Over in the British capital, Transport for London (TfL) – the British capital's governing body for transport – announced that it would only be able to carry around an eighth of the normal number of passengers because of social-distancing measures.

And despite the requirement to wear face masks helping to increase capacity in major urban transport hubs – McKinsey estimates it could bring it up to 40 percent – the industry has had to react quickly as people start to return to work across the continent.

Read more: How are Europe's metros coping as lockdowns ease?

During lockdown, traffic volumes in several major European cities were reduced by between 70% and 85%, according to sat-nav company TomTom. /Rudy Sulgan / Getty Creative / VCG

During lockdown, traffic volumes in several major European cities were reduced by between 70% and 85%, according to sat-nav company TomTom. /Rudy Sulgan / Getty Creative / VCG

In response, think tanks such as the UK's Institute for Fiscal Studies are floating the quick-fix solution of increasing ticket prices at peak times to help manage numbers, while Paris has been reopening subway lines at differing rates and suspending entry to certain stations. Staggering of start times for schools, offices, and public services is also playing an important role, with several Dutch schools and universities spreading start times over the day.

However, tweaks to prices and schedules will not be enough to mitigate the monumental shake-up of urban mobility amid COVID-19. With the remote working revolution keeping more than a third of Europeans away from the office, the pandemic is likely to lead to a permanent shift in commuting culture that has to be addressed in the long term.

"The COVID-19 pandemic makes everyone question what their real needs are or what kind of basic infrastructure we need in a city," says Moritz Maria Karl, an urban specialist and architect at the Berlin Institute of Technology. "This could be an opportunity to completely rethink the way we build cities."

And, indeed, the pandemic is already set to usher in a new age of urban transit that could change the urban life for good and, arguably, the better.

Read more: Planning for a green restart post-coronavirus

00:26

The only winner of the pandemic seems to have been the environment.

- Ivan Harbour, architect and partner at British firm RSHP

The key area that cities will have to build on to post-pandemic is the unprecedented drop in urban pollution levels.

While emissions are slowly creeping back up as lockdowns ease, in the UK, nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels were still 30 percent below normal as of 1 July, according to York University research. For Ivan Harbour, architect and partner at the renowned British firm RSHP, "the only winner of the pandemic seems to have been the environment".

"With pollution dropping to a point where it might have been in pre-industrial times, this emergency gives us a window to see what a carbon-neutral future could be like."

Exposure to pollution in the metropolis already accounts for around 4.2 million deaths each year, according to the World Health Organization, and now scientists are investigating a direct link between poor air quality and an increased threat from COVID-19.

New Delhi's air quality improved drastically between November 2019, top, and April 2020 because of lockdown measures to curb COVID-19. /Manish Swarup / AP Photo

New Delhi's air quality improved drastically between November 2019, top, and April 2020 because of lockdown measures to curb COVID-19. /Manish Swarup / AP Photo

One study from Harvard University found that even when accounting for other medical and socioeconomic factors, people living in places with poor air quality were more likely to die from the novel coronavirus. Another report from the Universities of Cambridge and Birmingham on London showed a connection between higher NO2 levels and increased risk of viral transmission.

According to Aaron Bernstein, interim director of Harvard's Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment, such findings are "consistent with prior research that has shown that people who are exposed to more air pollution … far worse with respiratory infections than those who are breathing cleaner air."

The research is still in its infancy, but if links between the virus and pollution levels are solidified, the future of urban transit will have to combine low emissions with extra space for commuters.

And this will ultimately justify one of the signature trends of pandemic-based urban retrofitting around Europe – the rapid extension of cycle path networks as part of a long-term trend to zero-carbon personal mobility.

Read more: Before and after: Air quality amid COVID-19 pandemic

02:08

City bodies are becoming ever more aware that making cities safe amid COVID-19 cannot be untangled from the threat of urban pollution. And as a result, Europe's most responsive metropolises are priming to kill two birds with one stone – with low-carbon coronavirus recovery plans, nearly all of which center on the socially distanced bicycle.

"Cycling is still the easiest and the best way to commute in a city," says Moritz Maria Karl, an urban specialist and architect at the Berlin Institute of Technology.

Despite all of the other potential technology at hand to deliver us to our destinations amid a pandemic, he considers this low-tech solution to urban transit strain to be far more practical and sustainable for city life: "It's so much more beneficial for your health and for polluted cities."

Milan, the capital of Europe's former coronavirus epicenter, Italy's Lombardy region, and the EU's most polluted city in 2008, led the way in adapting its streets to the crisis, announcing the transformation of 35 kilometers of road space into cycling and walking lanes in late April.

Milan has adapted its streets to the crisis, announcing the transformation of 35km of road space into cycling and walking lanes. /Claudio Furlan/LaPresse via AP

Milan has adapted its streets to the crisis, announcing the transformation of 35km of road space into cycling and walking lanes. /Claudio Furlan/LaPresse via AP

The early examples of the city's new bike paths are now congruous, with the number of cyclists doubling in recent months. This was, in part, thanks to a government scheme that offered city-dwellers up to 500 euros ($570) towards a new bicycle – as well as other low-carbon mobility methods such as electric scooters – resulting in an increase of nationwide sales by 60 percent in May.

But the room for these new cycling lanes didn't appear out of nowhere. Parking areas and motorist lanes were quickly annexed during lockdown to make room for Milan's bicycle boom, with similar measures mirrored in other European metropolises in what is already looking like a long-term move to reclamation of road space.

Watch: Are electric scooters the future of transport in the city?

Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo has pledged to reshape formerly busy roads around the French capital to allow for the greening of Paris's boulevards. /N. Bascop / Paris en Commun

Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo has pledged to reshape formerly busy roads around the French capital to allow for the greening of Paris's boulevards. /N. Bascop / Paris en Commun

If we want to make transport in London safe and keep London globally competitive, then we have no choice but to rapidly repurpose London's streets for people

- Sadiq Khan, London mayor

For RSHP architect Harbour: "The most interesting urban response to the pandemic is the idea that in order to achieve social distancing, we hand over the biggest space we have in the city to everyone and that is to use roads as pavements."

As part of wider plans to restructure the French capital away from the car and towards the bicycle, Mayor Anne Hidalgo has pledged to reshape formerly busy roads to allow for increased cycling use. But this also means the pedestrianization and greening of Parisian boulevards.

On streets where the number of car lanes are reduced, pavements will be widened for terrace space, urban architecture and newly planted trees, breathing new air and life into its highly congested streets.

Watch: London becomes green experiment as pollution hits record low amid lockdown

On Paris's streets where the number of car lanes are reduced, pavements will be widened for terrace space, urban architecture and newly planted trees. / SCD /Paris En Commun

On Paris's streets where the number of car lanes are reduced, pavements will be widened for terrace space, urban architecture and newly planted trees. / SCD /Paris En Commun

This is a long-term answer to providing personal space in ageing cities with narrow roads. In London, where two-thirds of the city pavements aren't wide enough to follow social distancing rules, pedestrian traffic increased five-fold following the arrival of COVID-19. This has prompted plans for another far-reaching car-free initiative centered on the needs of the pedestrian.

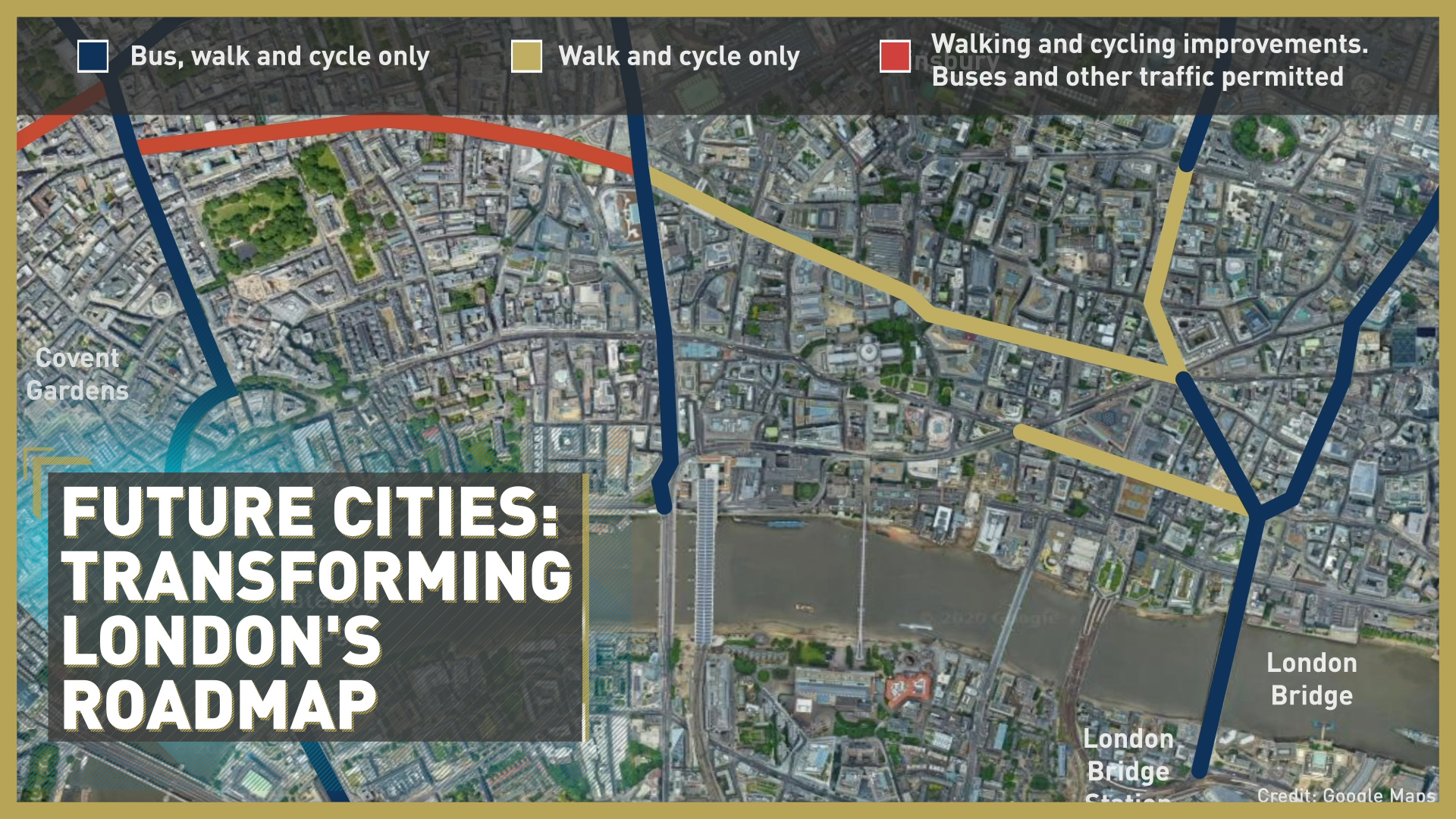

With the UK's $2.45 billion investment scheme to provide wider pavements and improve cycling infrastructure across the country, London Mayor Sadiq Khan has pledged to limit cars along several major traffic arteries, allowing only buses, cyclists and pedestrians to use what were once some of the city's busiest roads.

According to the mayor, many more Londoners will have to walk and cycle to make this work: "That's why these plans will transform parts of central London to create one of the largest car-free areas in any capital city in the world."

00:10

The City of London, separately governed from the wider city, is also exploring plans to reallocate street space for cafe terraces and al fresco dining, allowing for easier social distancing as lockdown eases in the UK.

"If we want to make transport in London safe and keep London globally competitive," said Khan, "then we have no choice but to rapidly repurpose London's streets for people."

However, the move to car-free zones has long been in the pipeline in London, and it's yet to be seen whether the authorities can successfully negotiate the plans with the city's motorists, many of whom rely on road access for their livelihoods. Cities such as Norway's capital Oslo have managed to pedestrianize large amounts of the urban center, but the change took several years following a major backlash from drivers.

And now that lockdown is easing, one fear is that gas-guzzling cars will once again be part of the "new normal," returning to the streets in ever-larger numbers.

Watch: UK's $2bn COVID-19 bike infrastructure plan could transform the country

Volvo CEO Martin Lundstedt believes the pandemic will change attitudes to diesel cars and promote electric mobility options. /Michel Euler / AP Photo

Volvo CEO Martin Lundstedt believes the pandemic will change attitudes to diesel cars and promote electric mobility options. /Michel Euler / AP Photo

I think it would be naive to believe after some months, our customers come back into a showroom asking for diesel cars

- Martin Lundstedt, Volvo CEO

However, industry experts are hopeful this won't be the case in the long run, as the benefits of the reduced pollution seen during the pandemic push drivers to go green.

"Electrification will go faster," says Volvo CEO Martin Lundstedt. "I think it would be naive to believe after some months, our customers come back into a showroom asking for diesel cars. They will ask even more for electric cars. And that is speeding up."

And as new ways to navigate the city accelerate, the future of the privately owned car is also up for debate: "People don't necessarily want to own a car, but they want the mobility, the freedom to move," Lundstedt says.

"In big cities, we need to have car-sharing concepts," he adds. "Subscription will come more and more" And the revolution in private transportation hastened by the virus is also likely to be seen in commercial transport.

Read more: China leads the charging points surge ahead of electric car boom

Starship Technologies deployed knee-high robots to deliver groceries in the English town of Milton Keynes in March. /Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP Photo/

Starship Technologies deployed knee-high robots to deliver groceries in the English town of Milton Keynes in March. /Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP Photo/

With a third of Britons buying items online for the first time during lockdown and DHL reporting an increase from 5.3 million to 9 million parcel shipments per day in Germany, the European e-commerce boom is already under way.

But what does this mean for our streets? With McKinsey predicting that increased online sales could increase the number of delivery vehicles in cities around the world by 36 percent by 2030, without alternatives to delivery vans and lorries, emissions and traffic congestion could skyrocket.

This is where "smart city" technology comes into play. Essentially, smart cities use various digitized methods – sensors, mobile phones, even drones – to monitor the interconnected digital information in an urban environment. The data can then be processed – often with the use of artificial intelligence – to refine a city's infrastructure, reduce costs, and enhance the quality of life of inhabitants.

For commercial delivery, the use of new modes of electric autonomous transport – a key feature of Smart City tech already accelerated by the pandemic – could provide the solution for the future.

COVID-19 prompted the first rollout of autonomous delivery in the UK, with Starship Technologies deploying knee-high robots to deliver groceries in the English town of Milton Keynes in March. In eastern China, start-up Unity Drive Innovation used its electric autonomous vehicles, capable of carrying up to 1,000 kilograms of cargo, to deliver fruit and vegetables to communities during the height of the crisis.

Watch: Belgium's robots helping Europe combat the COVID-19 pandemic

Hungarian police officers used drones to find residents who failed to comply with lockdown restrictions. /Janos Meszaros/MTI via AP

Hungarian police officers used drones to find residents who failed to comply with lockdown restrictions. /Janos Meszaros/MTI via AP

The economic fallout of the crisis is likely to delay investment in rolling out mass-scale autonomous transport in Europe as companies focus on keeping an even footing, but the benefits of moving to green, automated delivery for the future are clear, particularly amid the growing number of localized lockdowns.

And while there are still major regulatory and technological hurdles to pass, the widespread use of drones during the pandemic, whether it has been to enforce social-distancing rules like in Spain or to supply medical provisions in rural Scotland, is expected to proliferate in the commercial sector.

One report from tech manufacturer Protolabs found the challenges posed by COVID-19 were making aerospace business leaders more willing to embrace drone technology, pushing up appetite from 11 percent to 53 percent in just a few weeks.

According to Bjoern Klaas, vice president of the company's European wing: "Depending on legislation and advances in technology, it's feasible that last-mile delivery of products through drones could reach up to 30 percent of citizens across Europe."

Watch: How drone technology is changing emergency medical assistance?

Smart cities use various digitized methods to monitor the interconnected digital information in an urban environment. /VCG

Smart cities use various digitized methods to monitor the interconnected digital information in an urban environment. /VCG

If you think about the city and all these needs that people have ... a very interesting way of using AI and Big Data would be to filter these needs

- Moritz Maria Karl, architect and researcher at the Berlin Institute of Technology

The impact COVID-19 is having on urban mobility and transport infrastructure is profound, but so are the latent effects on city life of shutting down stations and pedestrianizing streets. Like the coronavirus, its progression will have to be closely monitored if cities are to make any kind of transportation revolution work.

Again, the use of Smart City technology and AI can play a role here. The pandemic has already ushered in a new age of digital monitoring, with facial recognition technology being rolled out in China, South Korea, and Singapore. In Europe, the most obvious example is contact tracing, with 50 countries worldwide using apps to connect and process urban environments to pinpoint and protect sites of infection.

But while privacy concerns continue to dog the conversation of AI monitoring in Europe, even data protection campaigners consider many of the tracing programs to be proportionate and necessary in the current crisis. A smart city is supposed to make urban environments resilient, whether that's against a disease or a breakdown in infrastructure.

"We now employ AI systems because we have accumulated so much data," says architect Maria Karl: "It's used first and foremost to optimize existing systems and, of course, some of the biggest challenges we are currently seeing are in terms of mobility."

Watch: Explainer: Smart cities using tech to be greener and more efficient

German academics at the High Performance Computing Center of Stuttgart have been using 'twin city' in Herrenberg to model traffic management solutions and target areas with particularly poor air quality. /High Performance Computing Center

German academics at the High Performance Computing Center of Stuttgart have been using 'twin city' in Herrenberg to model traffic management solutions and target areas with particularly poor air quality. /High Performance Computing Center

A city is a conflict and this is what makes it so interesting

- Moritz Maria Karl, architect and researcher at the Berlin Institute of Technology

He touches on the push for autonomous vehicles, which use deep-learning algorithms to navigate the roads, but says that in light of the pandemic, there are perhaps more interesting ways to approach the technology.

"If you think about the city and all these needs that people have, it's such a massive amount of data that it becomes very difficult to identify the signal in the noise. A very interesting way of using AI and Big Data would be to filter these needs."

One of the cheapest ways to achieve this would be city-level "digital twin" systems. These are virtual replicas of cities where digital representations of complex urban networks are plugged with real-life data taken from urban monitoring devices. They then digitally trouble-shoot solutions to see which are most applicable and cost-effective in real-life, looking at urban transit infrastructure as a whole.

German academics at the High Performance Computing Center of Stuttgart have been using the technology in Herrenberg, a small city outside Stuttgart, to model traffic management solutions and target areas with particularly poor air quality. They have even developed an app asking residents to report their emotional responses to different areas in the city.

Read more: What is data's role in Smart Cities?

Smart Cities can trouble-shoot solutions to mass transit problems. / MR.Cole_Photographer/Getty Creative/VCG

Smart Cities can trouble-shoot solutions to mass transit problems. / MR.Cole_Photographer/Getty Creative/VCG

"This pandemic is showing us that not a single person is actually infected, it's our society," says Maria Karl, who stresses accountability as one of the most important factors in applying AI to how we navigate urban environments.

"I think maybe this is how we have to use AI, that we collectively identify what decisions we want it to make and where we want to apply it. I think then it becomes really beneficial for us as a society instead of just supporting the needs of an individual."

With governments in the UK and Germany already promoting twin city technology, the digital future of European urban transit will likely help us refine the integration of new technology and modes of transport amid the pandemic, potentially helping us to understand what makes a city truly livable.

Read more: COVID-19 and the city: How past pandemics have shaped urban landscapes

"When we talk about city-making we always talk about conflicts," says Karl: "A city is a conflict and this is what makes it so interesting."

This is particularly true of urban mobility in cities like London, where pre-pandemic, millions of city-dwellers once negotiated their individual space at rush hour, going shoulder-to-shoulder on trains, roads, and pavements to navigate the urban environment.

And cities adapt to the pandemic and stations like London's St Pancras slowly creep back to life, albeit with a one-way traffic system and a flurry of masks, such transit hubs will again become the site of where we hammer out the future identity of our cities.

"This moment gives us this possibility to collectively discuss the conflict and collectively find an answer to address it," the architect adds. "If we can translate this way of thinking to city-making, this utopia that people are thinking about could become real.

"This is the big power and potential of this crisis."

Video Editor/Graphics: Sam Cordell, Natalia Luz, Angela Martin, Riaz Jugon