01:00

Outbreaks are a fact of life, and the world remains vulnerable. We do not know where or when the next global pandemic will occur, but we do know that it will take a terrible toll, both on human life and on the global economy

- World Health Organization director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus

Over the past few months, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus – or Dr Tedros, as he is more commonly and snappily known – has become an unlikely household name. We have grown used to the bespectacled, moustachioed World Health Organization (WHO) director-general delivering updates on the COVID-19 coronavirus with an authoritative calmness belying the increasing global distress: the panic behind the pandemic.

That Dr Tedros stays firm but unflappable is all the more impressive given that he knew this was coming. The quote picked out at the top of this page comes from his introduction to a 2018 WHO publication called Managing Epidemics. It is packed with sage advice and quiet warnings about everything from Ebola to cholera, MERS to monkeypox: the whole alphabet of communicable diseases from avian flu to Zika.

Sadly, the following year the world suffered another outbreak and despite decades of preparation and billions of dollars of resources, it found itself floundering to contain an initially unremarkable virus with a relatively low mortality rate which unleashed unprecedented human and economic destruction across the modern world.

It's fair to say that neither the warnings nor the advice in Managing Epidemics have been uniformly heeded. It's probably also fair to say that the WHO itself will have been learning from the COVID-19 experience. Let's hope so, because we all need to learn from it.

In a series of articles CGTN Europe will seek to pull together as many lessons as possible from past pandemics, as well as the current one.

As the world grapples with the COVID-19 crisis, we look at the different strategies taken by different countries and advocated by scientists, doctors and health advisors. This piece is a summary of CGTN Europe's reporting on the issues below and more in-depth reporting can be found at the links under each chapter heading. There you will find details of the statistics and sources we have relied upon to assemble the components of the Pandemic Playbook series.

1. Recognize the problem

2. Understand the disease

3. Minimize the outbreak

4. Communicate the risks

5. Prepare your response

6. Treat the sick

7. Adapt your resources

8. Plan your exit

9. Seek the cure

10. Learn the lessons

Shoppers walk along Oxford Street in London. /Frank Augstein/AP Photo

Shoppers walk along Oxford Street in London. /Frank Augstein/AP Photo

A pandemic does not announce itself. It will not, initially, be a pandemic. It will be a curious cluster of cases, a statistical quirk, in a single place perhaps apparently off the beaten track. But in a globalized economy on a travel-shrunken planet there is no real "single place" any more: every track is beaten.

In 2019, aviation tracker Flightradar24 followed an average of 188,901 flights per day criss-crossing the globe. (Even in March 2020, the average daily number was around 145,000.) Modern transport networks can efficiently distribute a virus hundreds or thousands of miles within hours, making every flight a vessel for contagion.

00:20

So you have to be awake to that statistical quirk, because once cases arrive in any of the world's major cities, globalization will almost inevitably ensure it does not remain a local problem.

Recognition must be a smooth and efficient process. Medical establishments need to notice unusual patterns and report them upwards to the management, and that management should rapidly assess them and if necessary alert international authorities. Because, depending on its pathology, a little outbreak could well be on its way to becoming a pandemic by infecting thousands or millions of people across the country and the world.

00:20

Towards the end of 2019, the WHO – the international organization responsible for monitoring and preparing the world's response to global medical emergencies, led by Dr Tedros – was called in by the Chinese authorities. Since then, the WHO has been at the forefront of the global response.

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, which causes the disease COVID-19. /NIAID-RML/AP

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, which causes the disease COVID-19. /NIAID-RML/AP

Exactly when the WHO officially declares a pandemic is relatively immaterial. The moment your mystery illness is recognized as capable of being transmitted from human to human, you are already in the "pandemic alert" period because the virus has proved its ability to use humans as its unwitting carriers.

You are sailing into the unknown: one of the definitions of a pandemic (and they are perhaps surprisingly loose and arguable) is that it is the worldwide spread of a new disease. So you won't initially know how it spreads, you won't know when carriers are contagious, you won't know how lethal it is, and you won't know how communicable it is. But you need to find out.

00:31

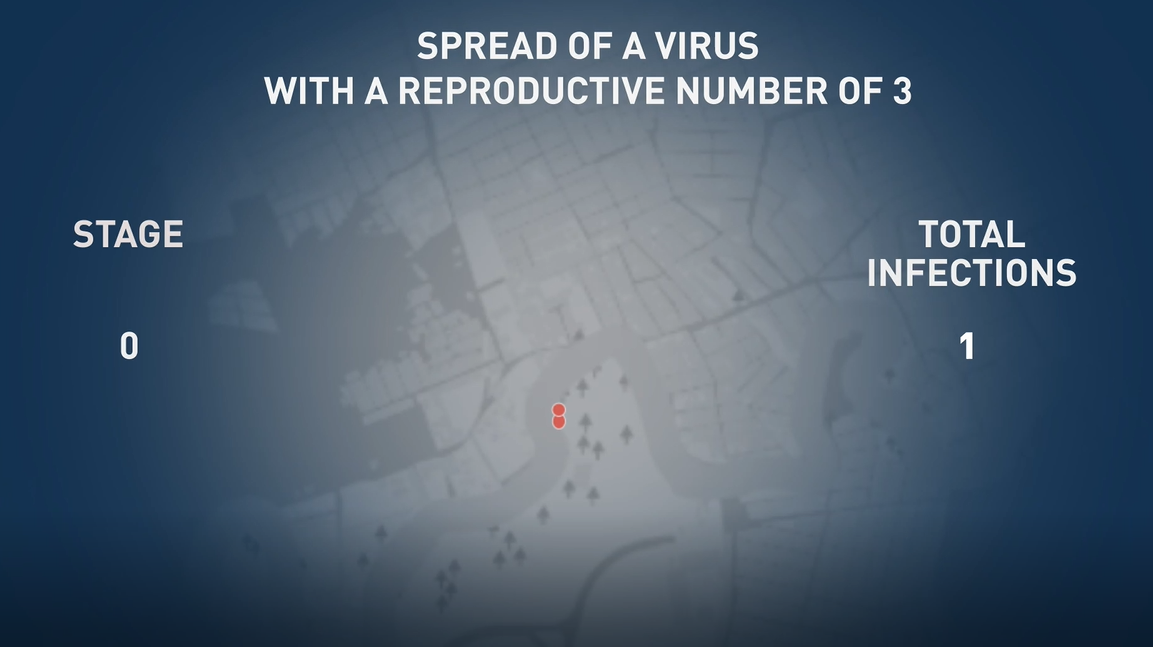

Take the reproductive number, for example, also known as R-nought or R-zero. If this is three, it means that every infected individual will infect an average of three others; that doesn't sound like much, but those three each infect three more, and by the 10th stage of transmission you have 88,000 people infected by that one original case.

If the R-nought is six, then 10 stages later your single case has spread to 72 million – equivalent to the total population of Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Greece, Hungary, Portugal and Sweden combined. The R-nought for measles is estimated to be between 12 and 18. Now you're listening.

Communicability is key. Many might assume outbreaks of a disease with a high fatality rate – such as MERS, which killed 35 percent of victims, or Ebola, which can range up to 90 percent – would be the worst-case scenario. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has proved this theory wrong.

So when an outbreak strikes, catalog cases and study the numbers using the best human and machine resources available. Sequence the genome and source analytical predictions to use and make plans. There is much to learn and not much time to do it in – because the disease is spreading.

A Spanish Civil Protection member poses with a face mask. /Jorge Guerrero/AFP

A Spanish Civil Protection member poses with a face mask. /Jorge Guerrero/AFP

OK, so you know not to underestimate the disease, but the unexpected little cluster has now become an outbreak – an accumulation of cases in close proximity and time. It's now up to you how bad it gets. Your strategy could save lives – or cost them. It might not be popular: it could mean a huge economic hit and some loss of civil liberties.

You might have to contain people entering the country, or prevent contact-spreading. You might have to isolate a lot of people with a prognosis you don't fully understand. And especially if the disease hides its contagious phase during a long uneventful incubation – like COVID-19, which can remain symptomless for up to 14 days while its carrier continues to interact and potentially infect friends, passersby, fellow commuters, shoppers or customers – you might have to do a lot of contact-tracing, which could involve data-harvesting to a level previously unheard of.

You will also have to conduct a lot of testing – both to see how wide the spread is and to understand more about the disease.

So how have countries decided to fight COVID-19 – and what have been the results?

Whatever you decide, you will have a lot of explaining to do to the public, but that's part of the next commandment…

Novice Buddhist monks in Bangkok, Thailand. /Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP Photo

Novice Buddhist monks in Bangkok, Thailand. /Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP Photo

Soon, your outbreak will be the only topic of news, and the public will react in different ways. Some will want to help as much as possible; others, their selfishness emboldened by their social media echo-chamber, will bridle against what they see as needless wing-clipping. Fake news and conspiracy theories will thrive.

All will need clear advice. This is about marketing and clarity of communication. You might need to explain new concepts (like social distancing) and codify some old ones (like hand-washing). And don't imply that only the old and sick are at risk, because if cases overwhelm your health service, everyone is.

You can try nudge theory – encouraging and incentivizing good behavior – but there is little time to waste and everyone needs to understand the urgency: you have a lethal unknown disease attacking your population. Couching your communication as "suggestions" will render them confusing to some and ignorable to many. Remember Teddy Roosevelt's theory: even if speaking softly, you may have to carry a big stick.

You will have to walk the line between causing complacency and sparking panic. Work with the private sector: most supermarkets will eventually self-police to prevent stockpiling but they watch market fluctuations more closely than anyone, so help them coordinate and listen to their insights.

More than anything, you will need to communicate clearly – a task administered with uneven success in the COVID-19 crisis.

ANALYSIS: How authorities, individuals and brands have explained COVID-19 - for better or worse

A grateful poster by artist Régis Léger/Dugudus in Paris, France. /Franck Fife/AFP

A grateful poster by artist Régis Léger/Dugudus in Paris, France. /Franck Fife/AFP

There will be a lot of advice from a lot of places that needs to be filtered quickly and prioritized. Some groups will have a vested interest, some may be well-meaning but inexperienced. Others have been thinking, preparing, and experiencing similar challenges on a more local level for many years – such as the WHO. Get a strategy.

Try to coordinate as widely as possible. Order relevant medical supplies such as personal protective equipment and ICU equipment, but also make sure your hospital cupboards don't empty of vital pharmaceutical aids such as painkillers and muscle relaxants.

Pass the emergency legislation necessary: to alleviate accusations of overreach these can, and probably should, be short-term. Recruit front-line responders: police, healthcare, military and volunteers. Create pride in teamwork and "all pulling together" even if it is essentially empty gestures like clapping on doorsteps. Encourage this sort of social glue, like singing on balconies. You may be spending a long time locking your people down: don't let them feel like you're locking them up.

Martina Papponetti, a nurse in Bergamo, Italy. /Antonio Calanni/AP Photo

Martina Papponetti, a nurse in Bergamo, Italy. /Antonio Calanni/AP Photo

Before long, your healthcare system may be on a war footing as hundreds or thousands of very sick patients emerge. Prioritization is key to sort the most urgent cases and cancel routine procedures to free up beds. At the same time, capacity in hospitals is likely to need expanding dramatically.

Field hospitals can be built fast, and spaces such as conference centres can be adapted relatively easily to temporary house thousands. Many densely urban centres around the world lack space because they are ports; here, large ships such as hospital ships or cruise ships can be used. Rural towns can be served by pop-up hospitals or hospital trains which can transport or treat the sick.

While you are expanding your capacity, you may need to juggle your logistics. Remember you are trying to fight an infectious enemy, and you may not have as many resources as you'd like. Whatever your existing sites and new spaces, think carefully about where to treat outbreak victims and where to house vulnerable other patients.

Crucially, protect the health workers who you and your people are depending on in the fight for life. Be very wary of the new disease and its pathology: like COVID-19, it may hide in plain sight, especially if your front-line health workers are underprotected. If they fall ill, they may unwittingly infect more people than they save. They are your troops, without whom you cannot win the war.

Patient transport to hospital needs to be considered as ambulance fleets are limited and public transport should be discouraged. You can relieve and reinforce your corps of ambulance crews by swiftly retraining and redeploying firefighters, military personnel or HGV drivers. And that brings us on to the next point.

Mattress-makers produce face masks in Phoenix, U.S. /Ross D. Franklin/AP Photo

Mattress-makers produce face masks in Phoenix, U.S. /Ross D. Franklin/AP Photo

It has been said that if necessity is the mother of invention, its father is desperation. If your country is in lockdown, your economy will be in freefall. If quarantine is widespread, expenditure will plummet and although some businesses can go online, others cannot – notably the service industry on which so many countries depend.

You may also find that other countries further up the supply chain have ceased operations, freezing up your own wheels. As your population finds itself out of work, you must brace yourself for a huge, perhaps historic, welfare burden even if you've spent a decade in painful austerity. And even when this short-term squall passes, you could be in for years of heavy weather as competing local economies scramble to reassert themselves globally.

However, not all is bleak. You will probably also suddenly have spare resources – human and manufacturing. During wartime, factories and their workers are often redeployed. If you are at war with a virus, what can you do? What can you make?

You may find you have clothing factories standing idle while your citizens cry out for face masks. Perhaps your previously thrumming automotive factories can be retooled to pump out hospital equipment. Changing tack might cost a little, but not as much as laying off the entire workforce – and governments can share the short-term burden with firms.

At the public level, you can make this a matter of pride – "How can YOU help us through this?" Encouraging people to make their own hand sanitizer or face mask may be the new Dig For Victory. At the corporate level, you can invite your brightest brains to be the heroes of the hour – a story that will have plenty of PR benefits when things settle down.

At the international level, this can be a good time for a little cooperation: if you have a strong scientific base and your neighbor has lots of factories, you might have the combined ability to defeat this virus. Think laterally in order to work cleverly – and help your people back to (safely distanced) work.

A drive-through testing facility in a Cypriot village. /Iakovos Hatzistavrou/AFP

A drive-through testing facility in a Cypriot village. /Iakovos Hatzistavrou/AFP

Nothing lasts forever. Pandemics and patience have a shelf life. A vaccine may become available, the reproductive rate drops or your restrictive measures choke off its communicability – or perhaps all three in some combination – at some point, the virus will become less of a concern and your people can start to tentatively come out from behind the doors.

Your questions are: when and how? Do you rush joyfully back into the streets, or wait a little longer to be on the safe side? Can everyone come out at once, instantly maximizing the reproductive danger, or do you permit a staged relaxation of restrictions? A loose lockdown is much harder to police than a blanket curfew, and patience is also a finite resource. Will people acquiesce to yet more time behind closed doors if their neighbors are back out on the streets?

While you wrestle with these troublesome topics, you have to stay committed to the work you have started – namely testing as many people as possible, better to know your enemies' movements. Don't stop until you've tested everyone, and even that might not be enough if there's a second wave.

You may not be the first to come out of lockdown, but it's not a race: learn lessons from others, both what works and what doesn't. Your people will be looking to you for answers, and you might be tempted to be strong and decisive when you need to be honest if you're unsure.

ANALYSIS: Exit strategies: Can things ever go back to 'normal'?

Work on COVID-19 testing kits near Tehran, Iran. /Ebrahim Noroozi/AP Photo

Work on COVID-19 testing kits near Tehran, Iran. /Ebrahim Noroozi/AP Photo

Everybody wants to be a hero. The idea of conquering a frightening new foe is at the heart of human nature, and finding a vaccine is the modern equivalent of slaying the dragon.

But science can be painfully expensive. Researchers need resources, just as you're finding yourself stretched to the limit. Again, international cooperation will be vital, financially and logistically. Sequencing the genome may not be as exciting a phrase as finding the vaccine, but it's often the vital first step.

And science can be painfully slow. Even if a potential vaccine is found, it has to be thoroughly tested over the course of weeks, if not months: rushing to market with an unproven product could kill.

There is rarely a quick and easy answer. In the meantime, you can continue to learn as much as possible about the nature of the disease. You can find new methods of treatment which can alleviate the stress upon both victims and the healthcare system.

The previous global pandemic, HIV/AIDS, still has no cure, but the treatment and prognosis is far ahead of what it was. While you seek the cure, try to understand the disease. The lessons you learn may not only be of use in this instance: they may change medical knowledge in a way that is less conspicuous than finding a vaccine but still heroic.

A COVID-19 victim is cremated in Lommel, Belgium. /Francisco Seco/AP Photo

A COVID-19 victim is cremated in Lommel, Belgium. /Francisco Seco/AP Photo

As the pandemic comes toward its end, the temptation will be to discover where it started. The search for Patient Zero can seem something like a witch hunt, but it must be an academic exercise in preventing repetition.

Disease detectives, or contact tracers as they prefer to be known, can help track the spread of a virus. Knowledge of its transmission routes can minimize recurrence and could very well also help prevent the spread of similar viruses in future.

The source is also important. Often, the viruses that cause pandemics cross from an animal, and the manner of that transmission can inform our relationship – both our intentional husbandry of livestock and our accidental interference in wild habitats.

There will also be changes to the way we live. They may be obvious: perhaps the face mask will become as accepted, if not even expected, in Europe as it is in many countries on the Pacific Rim. They may be subtler: less inclination to travel afar and more interest in rediscovered local parks, perhaps, or a greater prevalence of plastic germ-shields in supermarkets.

The important thing is to learn those lessons. Forewarned is forearmed, and while the next pandemic may behave in slightly different ways, the more we know, the safer we are.

Main image for Pandemic Playbook /izusek/Getty Creative