03:29

With Russia sending tens of thousands of troops to Belarus, Ukraine has been bolstering its border defenses. One section is particularly difficult to occupy though: Chernobyl, the site of the worst nuclear accident in history, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency.

For kilometer after deserted kilometer around this part of Ukraine though, radiation levels are still not safe. Even today, what remains of Chernobyl's nuclear power plant reactor requires a shield to protect human life.

Journalists being admitted to the exclusion zone are accompanied by Ukraine's military, who warns them to stay on the paths over concerns that radioactive dust spread all those decades ago can still do serious harm.

READ MORE

The psychological toll of Ukraine's conflict

Infrastructure becomes a target

Civilians train in preparation for escalation

Bags are not be placed on the ground. Anyone leaving must undergo a radiation check, just in case.

The apocalyptic disaster that occurred here in 1986 is seen by many as the one event that brought the end of the Soviet Union one step closer.

Now, Vladimir Putin wants to reverse what he sees as the humiliation that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. So this radioactive landscape can no longer remain vacant.

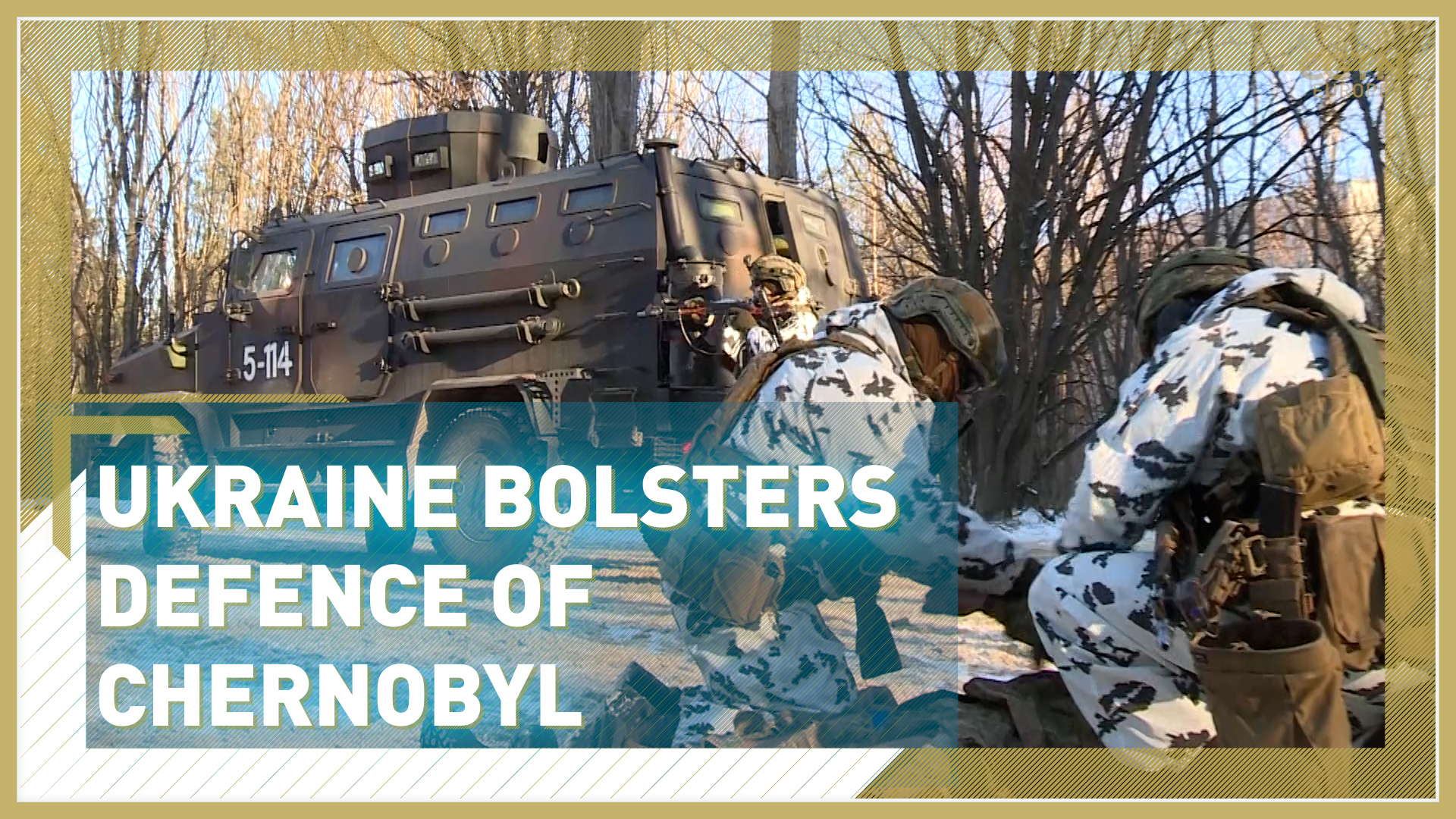

In the middle of the abandoned town of Prypet, just a few kilometers north of the ruined plant itself, Ukrainian special forces are conducting live-fire exercises.

They are accompanied by emergency services, whose role is to rescue soldiers and civilians in a close-quarters urban combat scenario.

They are supported by the National Guard, who in the last few weeks have been deployed to carry out patrols in the area, carrying mobile radiation monitors with them as they do.

Ukraine's National Guard soldiers take part in tactical exercises near the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. /AP Photo/Mykola Tymchenko

Ukraine's National Guard soldiers take part in tactical exercises near the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. /AP Photo/Mykola Tymchenko

As is common practice with such drills, the scenario is hypothetical. But there is little doubt that Ukraine has let us in so Russia can see that its forces would no longer be able to move through uncontested.

Because the border with Belarus is just a few kilometers north of here, and NATO says there are now 30,000 Russian soldiers on the other side of it. Western and Ukrainian military analysts do not discount the possibility that the Chernobyl exclusion zone could become a pathway for an attack on the capital, which lies less than 150 kilometers further south.

In addition to the risk of damage to the Chernobyl reactor's shield and the threat of radiation poisoning, there are yet more reasons an offensive through this area would be risky. Thick forests and swampland make it difficult to cross.

And on the eastern side of the Dneiper river runs a main road and easier terrain. [See map below]

But the heart of Kyiv lies on the river's west bank, the same side as Chernobyl. So, surveillance aircraft still scout the border areas, looking for even the slightest signs of any imminent advance. And a Ukrainian troop build-up in the area continues.

Chernobyl is 96km from Kyiv as the crow flies./CGTN Europe Creative

Chernobyl is 96km from Kyiv as the crow flies./CGTN Europe Creative

Just outside the exclusion zone, civilians are all too aware of what could come. Many remember the last time disaster struck this place. Tending to a century-old family fishing boat on the Dneiper's western bank, we find 72-year-old Vitaliy Kurinnoy.

On April 26, 1986, the day of the Chernobyl disaster, Kurinnoy spent time at the seriously damaged reactor managing the rescue effort. He won a national award for bravery for his efforts, but it came at a cost. Kurinnoy, unlike many of his friends and colleagues from the time, is still alive but he admits his health is failing him.

Chernobyl, he says, has seen enough.

"I believe Europe and the U.S. will stop Vladimir Putin. But I still have anxiety in my soul because nobody really knows what is on his mind," he says.

Everyone we meet around the edge of the exclusion zone is jittery but few are preparing to leave. 37-year-old Lyubov Belets has a business to tend to and much more than that.

"We'll stay for sure, where else would we go?" Belets says. "My whole family are here, including my parents. I can't leave them."

Ukraine's defense minister has come to see these drills first hand: so it certainly looks like they hold some significance. Even if the government line remains to play things down.

"Today, Russia's cumulative forces taking part in exercises in Belarus number several thousand, which is not enough to carry out an independent invasion," Oleksi Reznikov tells a gathered group of personnel and journalists.

Chernobyl's unique dangers would make this a precarious place to fight. But if no battle plan survives first contact with the enemy, war here cannot be ruled out.