03:56

"We don't want to go to Syria. We have nothing left there."

Bahra Sukur was eight when he and his family arrived in Germany. His homeland, Syria, had erupted into civil war and now, a decade later, more than half a million Syrians have been killed and millions more, like the Sukurs, have been displaced.

Bahra's mother Hala tells CGTN Europe: "There were bombings everywhere and we were always afraid of being arrested, we were also very afraid for our children that they would disappear, because of this and for other reasons we had to flee to Lebanon."

Despite having six restaurants in the capital Damascus, the family saw no other option than to leave everything and flee their home.

READ MORE

The spray that kills 99.99% of COVID-19

Who has stopped using AstraZeneca vaccine?

More twins being born than ever before

Over the next two years, the Sukurs found themselves trying to carve out a life for themselves in Lebanon, Egypt, Dubai and Turkey. That is before being granted a German visa in 2014 through Germany's Family Reception program, a two-year program that accepted a total of 20,000 Syrian refugees.

They struggled at first to learn the German language.

"Learning the German language is not easy," admits Hala. "There are so many terms, so many meanings for one word, and I still have to search and look up many words in the dictionary."

She says the next challenge was psychological "because after these two years that we had spent in several countries, we didn't know whether we could stay here in Munich or what would happen next."

Despite the unknown, they enrolled their children in local schools, tackled the language and looked for ways to do what they know best – run a restaurant.

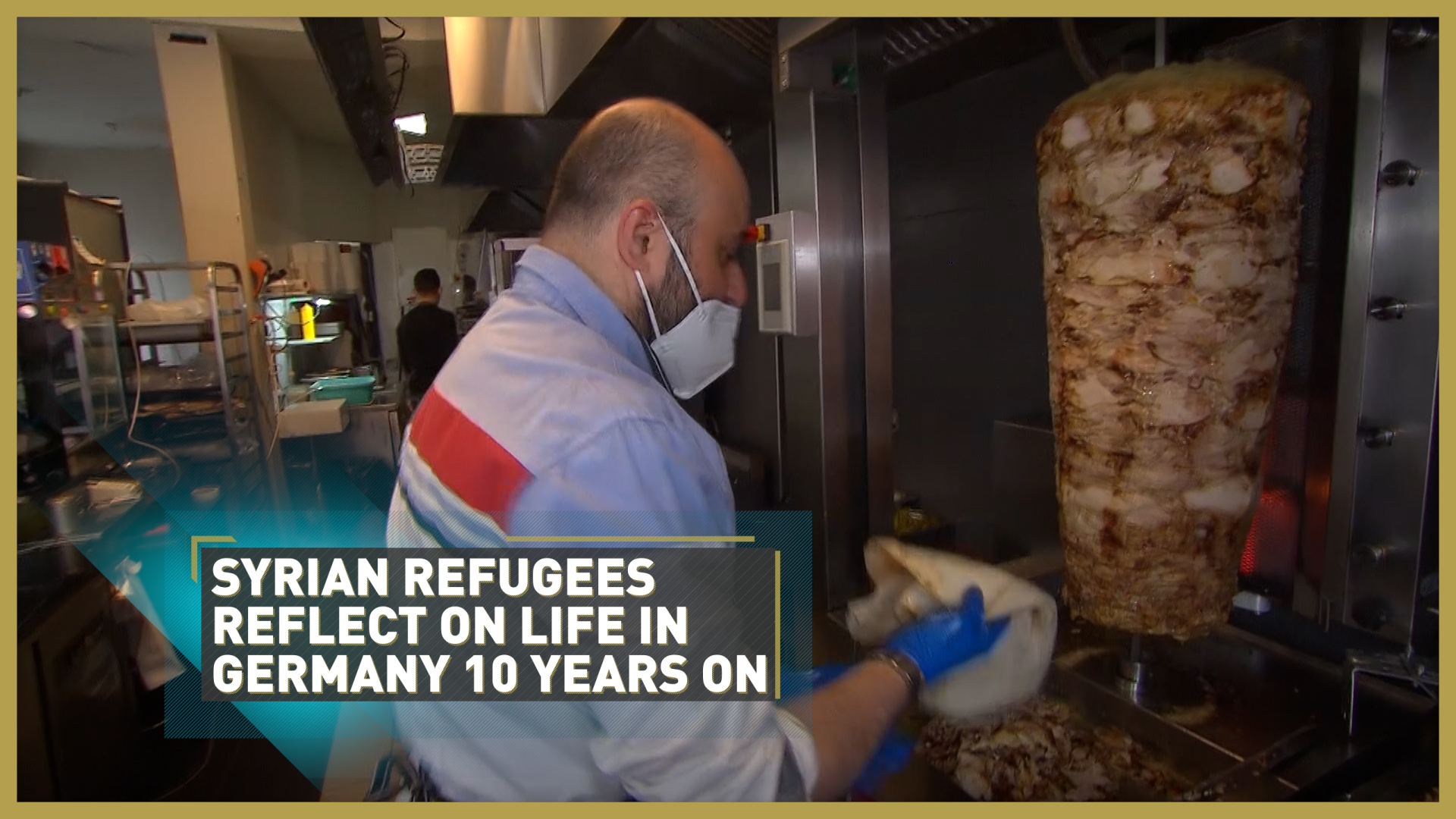

The Sukurs reflect on their lives in Germany 10 years on from the uprising in Syria. /CGTN Europe

The Sukurs reflect on their lives in Germany 10 years on from the uprising in Syria. /CGTN Europe

Today the Sukurs own Crispy and More, a popular Syrian fast food restaurant in Munich, which they are hoping to expand.

"As soon as we arrived here, we started working and established our first company in Germany," says Mohammed, as he shaves beef off a skewer of meat.

"Everything is easy here, the only problem is that we are in a foreign country and the language affected our business until we started learning German."

There are approximately 800,000 people in Germany with Syrian backgrounds, most of them arriving in 2015 via the Balkans route.

At that time, Germany's chancellor Angela Merkel famously welcomed refugees while other EU states were closing their borders to them. Berlin also waived the so-called Dublin rules for Syrian refugees, meaning those who arrived in Germany would not be sent back to the first EU state they had arrived in.

Germany quickly became the destination of choice for many people fleeing war and poverty. In 2015 and 2016, Germany received more than 1 million first-time asylum applications. However, it has not been easy.

The rise in refugees also gave rise to anti-refugee sentiment in the country. The debate between needing them to fill the shortage of skilled workers and them being a burden on Germany's social security funds was hotly contested and still is today.

Yet, having lost everything they ever knew back in Syria, the Sukurs feel grateful to have found a second home in Germany. They don't envision ever going back.

"After 10 years, the situation is still dire in Syria. The people there have no real living conditions. So far there is no light at the end of the tunnel, but I am optimistic and I don't want to lose hope," said Hala.

Nor do the millions of other Syrians spread around the world, all hoping that one day they can return home.