02:10

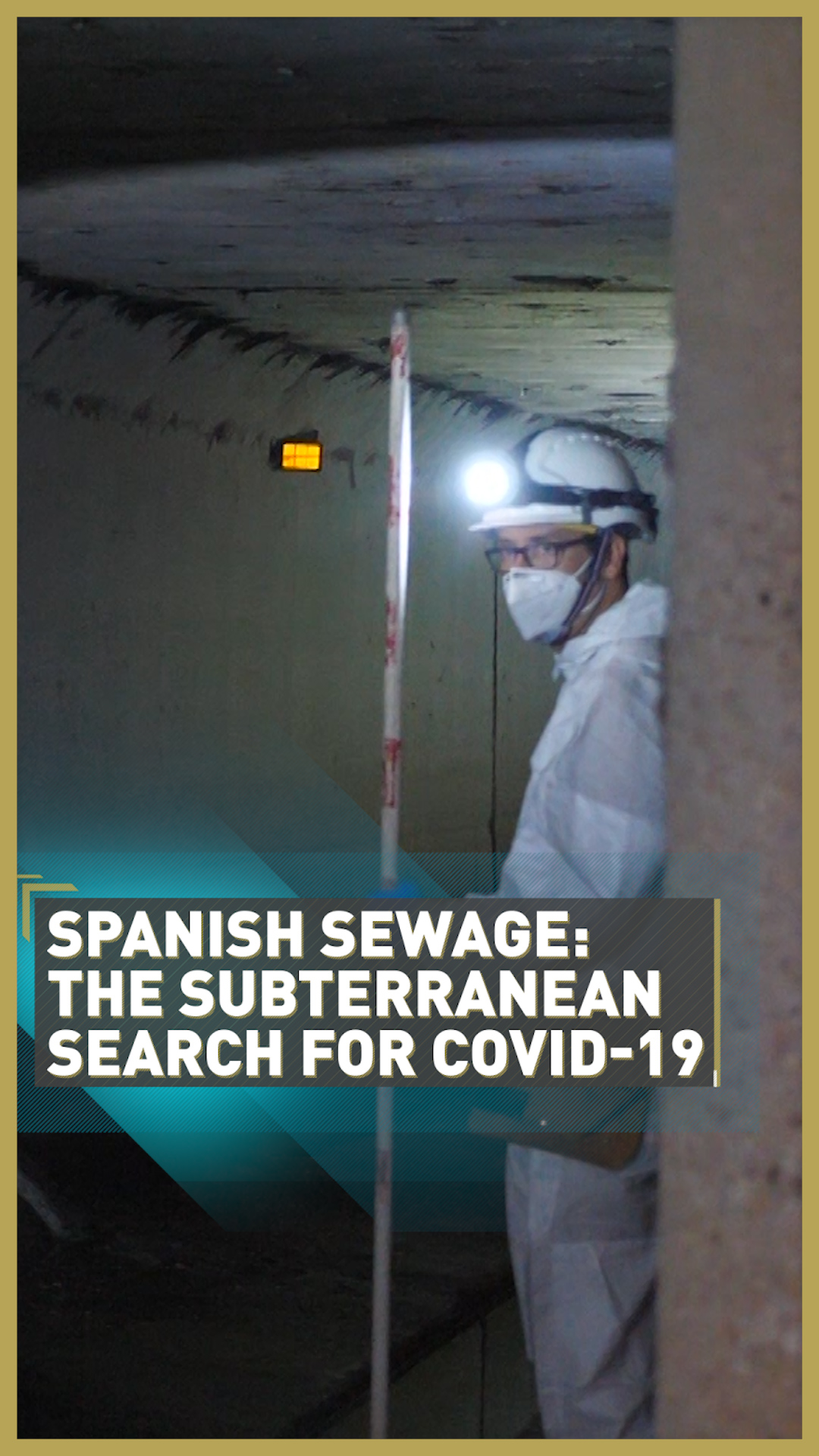

In the ongoing battle against COVID-19, authorities in Spain are heading underground, and to extreme levels, in an effort to find out more about the virus.

In the southern Spanish city of Valencia, the study of fecal matter in wastewater samples has resulted in the development of an early detection system that could help control outbreaks of the novel coronavirus.

And with Valencia registering one of the lowest infection rates of Spain's major cities, the hope is that the new sewage testing system will make sure that continues.

Watch: How testing sewage could help the UK predict COVID-19 outbreaks

In Valencia, the study of fecal matter in wastewater samples has helped to create an early detection system to control outbreaks of COVID-19. /CGTN

In Valencia, the study of fecal matter in wastewater samples has helped to create an early detection system to control outbreaks of COVID-19. /CGTN

High-speed testing

According to Guillermo Garcia, an analyst with the Valencia-based water company Global Omnium, testing the sewage system for traces of COVID-19 is surprisingly fast.

"The samples are collected in the city and sent to a lab, where it takes eight to 10 hours for them to be analysed," he tells CGTN. "Then the numbers are shared with the client, health authority or a company in real time."

The same-day delivery of such data is a huge achievement for the team. Speed continues to be one of the most vital criteria for allowing authorities to take pre-emptive measures in the event of a new outbreak.

Identifying the virus in waste or sewage water means local health authorities can isolate and control any potential outbreak far earlier than would be possible if they just waited for people in certain areas to show COVID-19 symptoms.

This gives cities like Valencia more than a two-week start on the virus – and with a possible second wave of the virus that could strike at any time, an early warning system becomes all the more necessary.

Samples are collected in the city before being sent to a lab, where it takes eight to 10 hours for them to be analyzed. /CGTN

Samples are collected in the city before being sent to a lab, where it takes eight to 10 hours for them to be analyzed. /CGTN

International interest

The system was developed by specialists from the University of Valencia and Global Omnium, and according to the water company's CEO Dionisio Garcia Comin, there is plenty of interest both at home and abroad.

"We had some interviews with New York City and we are also going to do it in Spain and other important Spanish towns," he says. "We are already collaborating with Sevilla and maybe in the future with Madrid."

If such systems can be made affordable, then their speed and simplicity could become a viable alternative to mass contact tracing, especially for poorer countries where there is less access to technological infrastructure.

The question will firstly be how reliable the data is and then how easy it will be to model the information at a wider scale so it can be used to pre-empt outbreaks at a national level.

But for now, Valencia is one of the European cities leading the subterranean march against COVID-19 – and it could save lives not only of its inhabitants, but city-dwellers around the world.

Read more: Sewage could be the 'canary in the coal mine' for COVID-19 second wave