03:27

Emmanuel Macron may have won the French presidential election, but he faces the possibility of "political gridlock" after June's parliamentary election.

That's the warning from political analyst Alexandre Kouchner, who says this election represents a "tipping point in French political history," as the country switches from the old two-party system to a new three-pole landscape with radical politicians chipping away at either side of centrism's support.

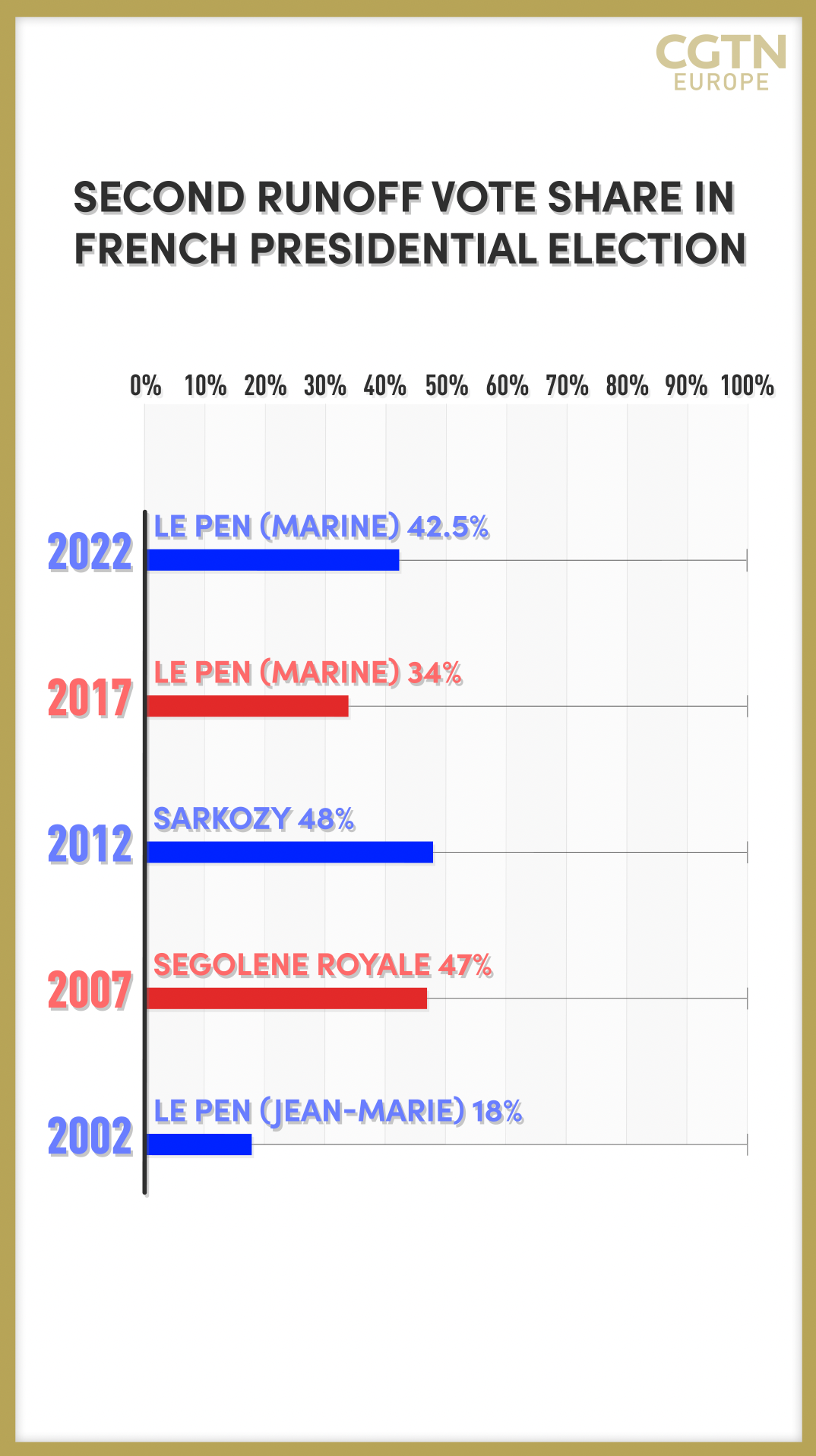

Kouchner says Macron's triumph was a hollow victory, with Le Pen's narrowing of his lead particularly painful given the president's pledge after the 2017 election.

READ MORE

Ukraine crisis threatens global food security

Bridge Builders: The Anglo-Chinese Guo family

1980s China: in photographs

"When Emmanuel Macron was first elected five years ago, he vowed to change the system so that no one would want to vote for Marine Le Pen again in the rematch," Kouchner told CGTN – but since then, "he lost two million votes, she gained three."

While Macron's first election heralded a new force in French politics – with the former Socialist Party member leading a new centrist and pro-European party En Marche – Kouchner puts this win down to a less positive reason: "This is not a vote of adhesion. The French voted for Macron because they hated Marine Le Pen just slightly more."

Further election problems loom

Macron could also face further problems in the elections for France's National Assembly, on June 22. He currently enjoys a majority in the 577-seat assembly, with En Marche's 267 seats bolstered to 346 by partners Democratic Movement and Agir Ensemble.

However, Macron's political enemies are gearing up to reduce his power by electing a hostile assembly. Hard-left presidential candidate Jean-Luc Melenchon, who came third – just behind Le Pen – in the April 10 first round of the election, told supporters "Don't give up – you can beat Macron [in the parliamentary election] and choose a different path."

Meanwhile, Le Pen's niece Marion Marechal – who defected to support hard-right challenger Eric Zemmour – urged right-wing party leaders to discuss a parliamentary pact. "Without a coalition, Macron will have all the powers and Melenchon will be the first opposition group," Marechal wrote on Twitter. "With a coalition, we can turn the national camp into the biggest force in the Assembly!"

00:27

While historically the president's party has usually won a parliamentary majority, France's system allows for the so-called 'cohabitation' in which the president and the assembly-leading prime minister are from different parties. During a cohabitation, the president remains the head of the armed forces and retains some foreign policy influence but the government has responsibility for most other day-to-day matters of state and policy.

"Should Macron not be able to have a clear majority in parliament, he could have to deal with a government he does not control," explained Kouchner. "This could either be Jean-Luc Melenchon, a radical leftist who has done very well in the last election, or Marine Le Pen – in which case this would end up in a political gridlock."

Key election discussion points

Kouchner notes that Le Pen had success by softening her previous right-wing rhetoric – and that a new, harder-line polemicist helped to confirm her less extreme views.

"The turning point was for Marine Le Pen to not mention race and immigration. And she was helped by Eric Zemmour, [leader of] a radical extreme right-wing movement, whose rants about immigration made her seem more poised.

"What was really on the French electorate's mind was purchasing power. And this is also why Le Pen was rather successful – she turned from race and immigration to bread-and-butter issues, and that served her very well."

Attacked from the left and the right: centrist Macron lost some support to left-winger Jean-Luc Melenchon as well as right-winger Marine Le Pen. /Joel Saget/AFP

Attacked from the left and the right: centrist Macron lost some support to left-winger Jean-Luc Melenchon as well as right-winger Marine Le Pen. /Joel Saget/AFP

Macron, by contrast, was helped by global events in Ukraine – to an extent. "His international stature is seen by the French as something that serves the country," said Kouchner, although he says the French electorate's attitude to the conflict is complicated.

"Le Pen has public ties with Russia, she also has economic ties with Russia, yet this proximity did not hurt her in any way. It actually hurt Zemmour, who mentioned he would really like to be the French Vladimir Putin."

A new political landscape

For Kouchner, this election was of historical interest – confirming the demise of the two traditional parties usurped by En Marche last time, but also pointing to a new future for French politics.

"If historians look at this election, they will see a tipping point in French political history. It's the undoing of a two-party system – the Conservative Party and the Socialist Party are all but gone – and the rise of a three-pole political landscape: a radical left, a 'big tent'-style party with Emmanuel Macron in the center, and a radical right.

"The thing is, our institutions are not exactly crafted for that sort of politics. So what's going to happen in six weeks is everybody's guess, but also crucially important for Macron."