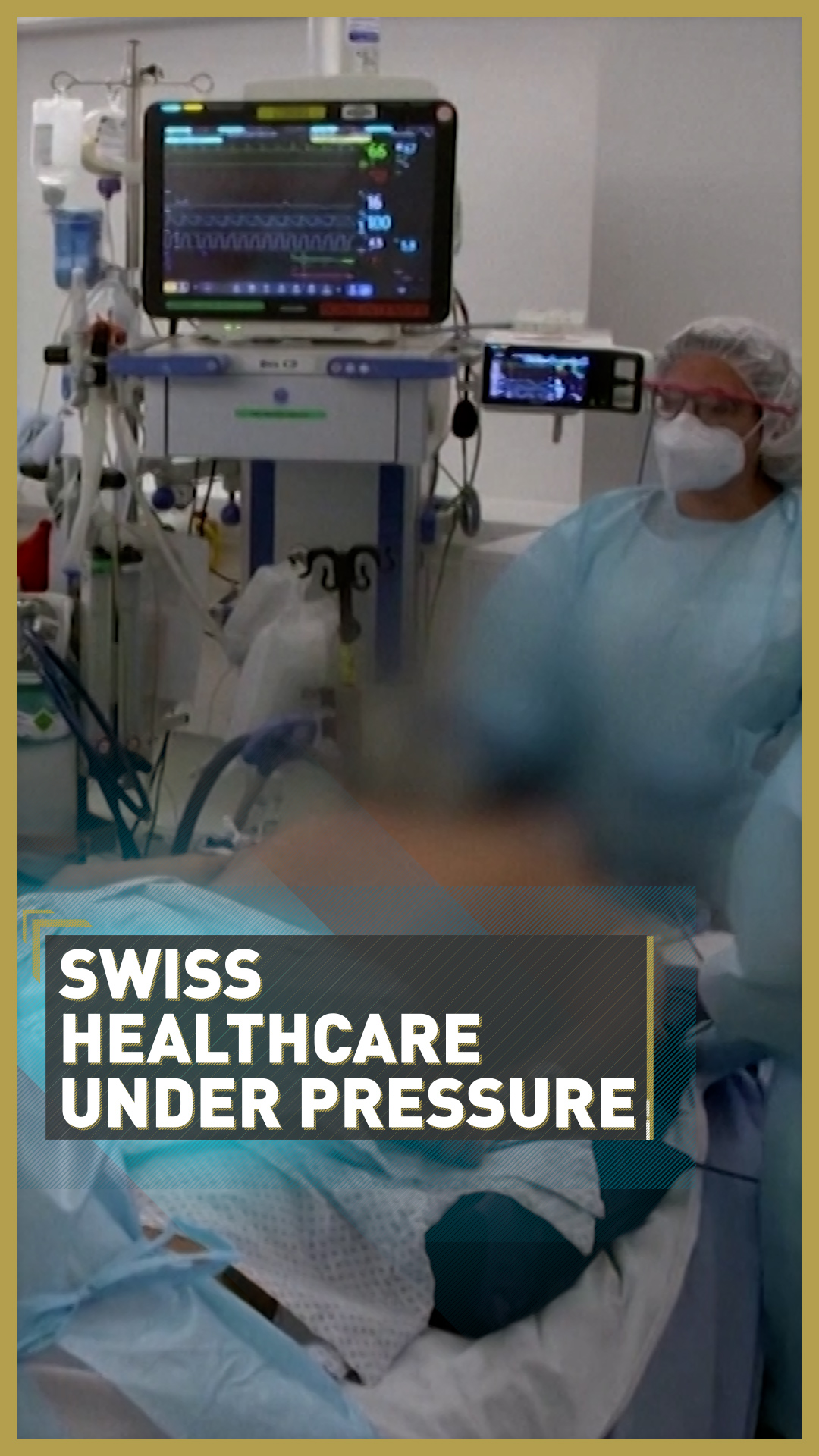

Is it acceptable to recommend patients refuse intensive treatment? That's the debate in Europe. /AP/Keystone/Martial Trezzini

Is it acceptable to recommend patients refuse intensive treatment? That's the debate in Europe. /AP/Keystone/Martial Trezzini

"After a certain age and with comorbidities, ending up in intensive care is not a certain lifesaver, but can be a torture."

That's Marco Vergano, an ICU doctor in Turin, discussing the reality for COVID-19 patients who are at risk of severe symptoms and need intensive care.

His colleague Antonio Cuzzoli was in charge of the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at the Cremona hospital in northern Italy during the first wave of the pandemic in Europe and told the media some of his patients were "heroes" for deciding to refuse such treatment.

The choice to avoid intensive and often invasive medical procedures by patients with comorbidities to COVID-19 (i.e. other underlying conditions) has another practical benefit; it frees up beds for other patients with serious COVID-19 symptoms.

01:04

In Switzerland this week, a debate is raging over advice given by a group of ICU doctors to patients to consider their end-of-life plans – with the issue of bed space put alongside the best care for patients.

The Society for Intensive Care Medicine (SGI) said people aged over 60, or with health conditions such as heart disease and diabetes, should put their wishes on paper in case they contract the illness and lose consciousness or the ability to communicate with medical staff.

"This will support your own relatives, but also the teams in the ICUs, as they make decisions so the treatment can be done in the best possible manner according to the individual patient wishes," the SGI said in a statement.

Perhaps unsurprisingly this advice has caused anger among some who see it as premature – especially as the country's ICU capacity is not currently at risk of running out of beds.

Pro Senectute Schweiz – a Swiss group that lobbies for the interests of older people – said the message from the SGI would usually be sensible advice, but as the world is gripped by a pandemic it only served to create panic where there isn't an emergency.

"The SGI appeal ... takes place in the context of an absolute emergency situation in which Switzerland does not yet find itself," the group said.

SGI president Thierry Fumeaux, an ICU doctor in the Swiss town of Nyon, replied that, "this is not a call for sacrifice. It's just a call to take responsibility for their autonomy."

He said it was about thinking ahead – rather than attempting to panic those who may be at risk, or sending a message that vulnerable people should not get the same care as others.

It's an uncomfortable subject, but ICU beds are limited – often severely so. /AFP/LOUISA GOULIAMAKI

It's an uncomfortable subject, but ICU beds are limited – often severely so. /AFP/LOUISA GOULIAMAKI

Switzerland, which has allowed people to end their own lives for many years, is perhaps one of the most open and forward-thinking nations in Europe when it comes to discussing end-of-life care, but Emma Cave, a professor of healthcare law at Durham University, said conversations like this need to happen everywhere.

Though the UK-based academic stressed that no patient, with COVID-19 or not, should be pressured into any decision, she said it was both a moral and a legal necessity to allow people the chance to express their wishes.

"A failure to have such a conversation risks not respecting their views and breaching their rights," she said.

And it seems Cave and the SGI are being heard. This week, the UK government's Department of Health and Social Care said it had asked a hospital and care home regulator to review "do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation" decisions made during the pandemic.

And in Germany, several cases are headed to the constitutional court over the ethics used to decide who gets treatment if hospitals become overloaded – and who should be responsible for writing up the rules.

Video editor: Natalia Luz

Source(s): Reuters