The pandemic has made wearing face masks in public an essential part of our lives, as governments encourage or make their use mandatory to prevent the spread of the virus. And face masks are likely to remain part of our daily outfits until a vaccine for COVID-19 is found.

In situations of shortage, people get creative with their face masks, from surgical masks and N95 respirators to home-made face masks, snorkeling masks, and even water jugs and salad leaves.

But as countries get better organized and face masks become widespread within the community, problems are arising.

02:12

Transparent masks to help deaf and those with hearing loss

There are 466 million deaf and people with hearing loss in the world, according to the World Health Organization, 34 million of those are children under the age of 15. While 34.4 million people with disabling hearing loss live in Europe.

"Standard face masks make lip-reading impossible and facial expressions very difficult to understand," explains Ian Noon, Chief Policy Advisor at the National Deaf Children's Society (NDCS). "Almost all deaf people rely on these communication techniques, so without them they're at an even higher risk of loneliness and isolation than usual. Face masks also muffle sound, so those deaf people with residual hearing will also find it harder to communicate."

Face masks can be especially intimidating for children, who lack the confidence needed to ask for something to be repeated. "If everyone wears a standard face mask, deaf people could face months of misery as they struggle to understand what people are saying to them," says Noon.

Kelly Morellon worked with her mother Sylvie to design a face mask with a transparent window that leaves the mouth visible yet still protected and is asking authorities to make these masks the norm.

Morellon works for the association 'Main dans la Main,' which supports deaf and people with hearing impairment in northern France, described face masks as a "catastrophe for people who are deaf or have hearing problems."

Kelly Morellon (on the right) with her mother Sylvie (on the left) wearing their homemade face masks with transparent panel. Credits: Kelly Morellon / Facebook

Kelly Morellon (on the right) with her mother Sylvie (on the left) wearing their homemade face masks with transparent panel. Credits: Kelly Morellon / Facebook

Kelly is one of the many people across Europe who are taking the matter in their own hands, whereas in Europe, transparent face masks are hard to find for sale.

Only two manufacturers in the U.S. produce face masks with clean panels that are safe to be used by healthcare workers, and none in Europe at the moment. But the NDCS has shared an online tutorial for people to learn how to make their own at home.

"We've written to NHS England to ask them to look into making transparent face masks widely available," says Noon. "However, we'd also ask the general public to develop their deaf awareness, whether they're wearing a mask or not. Speaking clearly, using gestures, writing things down and finding a quiet place to chat will make a huge difference to deaf people."

The glamorous face shield designed by New York's designer Joe Doucet, here presented in a virtual photoshoot. Credits: Joe Doucet

The glamorous face shield designed by New York's designer Joe Doucet, here presented in a virtual photoshoot. Credits: Joe Doucet

Making the necessary desirable

Wondering how to encourage millions of people to wear an unwanted but necessary accessory, New York's designer Joe Doucet created a fashionable face shield that can be worn as a pair of sunglasses.

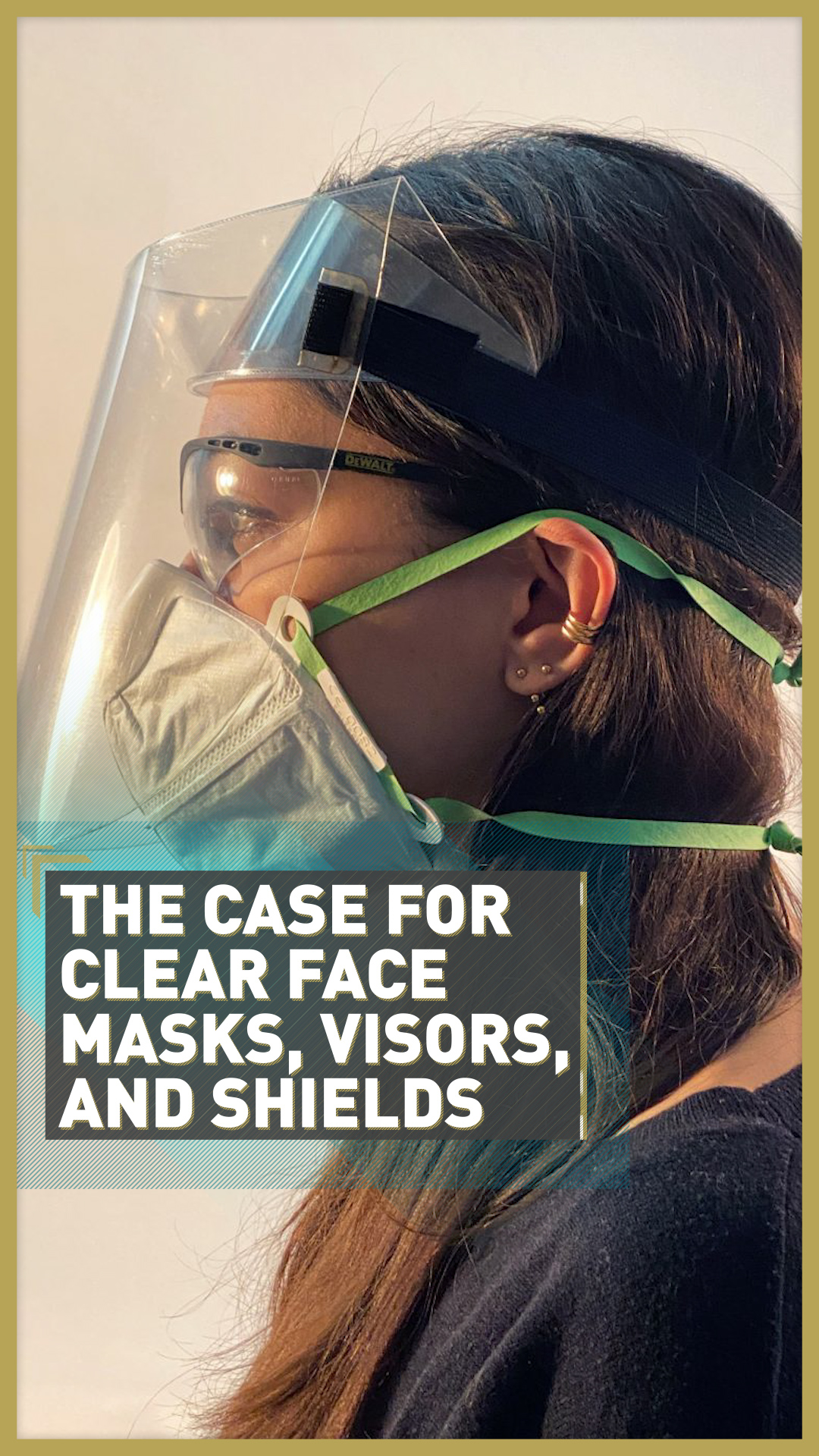

"According to leading epidemiologists, the best piece of protection anyone can have is a face shield, not just a face mask," says Doucet. "The challenge with face shields is that they are ungainly, they're cumbersome, they're inhuman. It is not normal - it makes us feel ill walking around.

"And so I began to think, how could we get one to want to wear a face shield? What behaviors already exists that we could co-opt and then design to make it much more palatable and even desirable? And one of the things we all do is we wear glasses at some point, whether they're sunglasses or reading glasses. This is not foreign behavior for us. It's just natural when you go outside, put on sunglasses."

An added benefit of these face shields, according to Doucet, is that it allows people to see each other facial expressions. "70 percent of communication is nonverbal," he explains. "And when you cut off those cues, we're beginning to see that this really heightens aggression and things like that, because I don't know what you're doing. You don't know what I'm thinking. You don't know if I'm smiling or if I'm angry. And this design completely negates that effect."

Doucet and his team are working day and night to get the product on the market as soon as possible, hoping for mass adoption.

The origami face shield for healthcare workers, Happy Shield, created by researchers in the UK. Credits: University of Cambridge and the University of Queensland

The origami face shield for healthcare workers, Happy Shield, created by researchers in the UK. Credits: University of Cambridge and the University of Queensland

An origami face shield for healthcare workers

Researchers at the University of Cambridge (UC) and the University of Queensland (UQ) have designed an origami face shield for healthcare workers assembled by folding a curved piece of transparent plastic.

The face shield, called Happy Shield, is inexpensive and easy to mass-produce, and can be made anywhere in the world by downloading the open-source design available online. The only materials needed are a clear sheet and an elastic band.

According to the researchers, the face shield is easy to rewash and comfortable to wear. These safe and cheap face shields could be particularly useful in less wealthy countries that struggle to provide PPE to their healthcare workers.

Check out The Pandemic Playbook, CGTN Europe's major investigation into the lessons learned from COVID-19