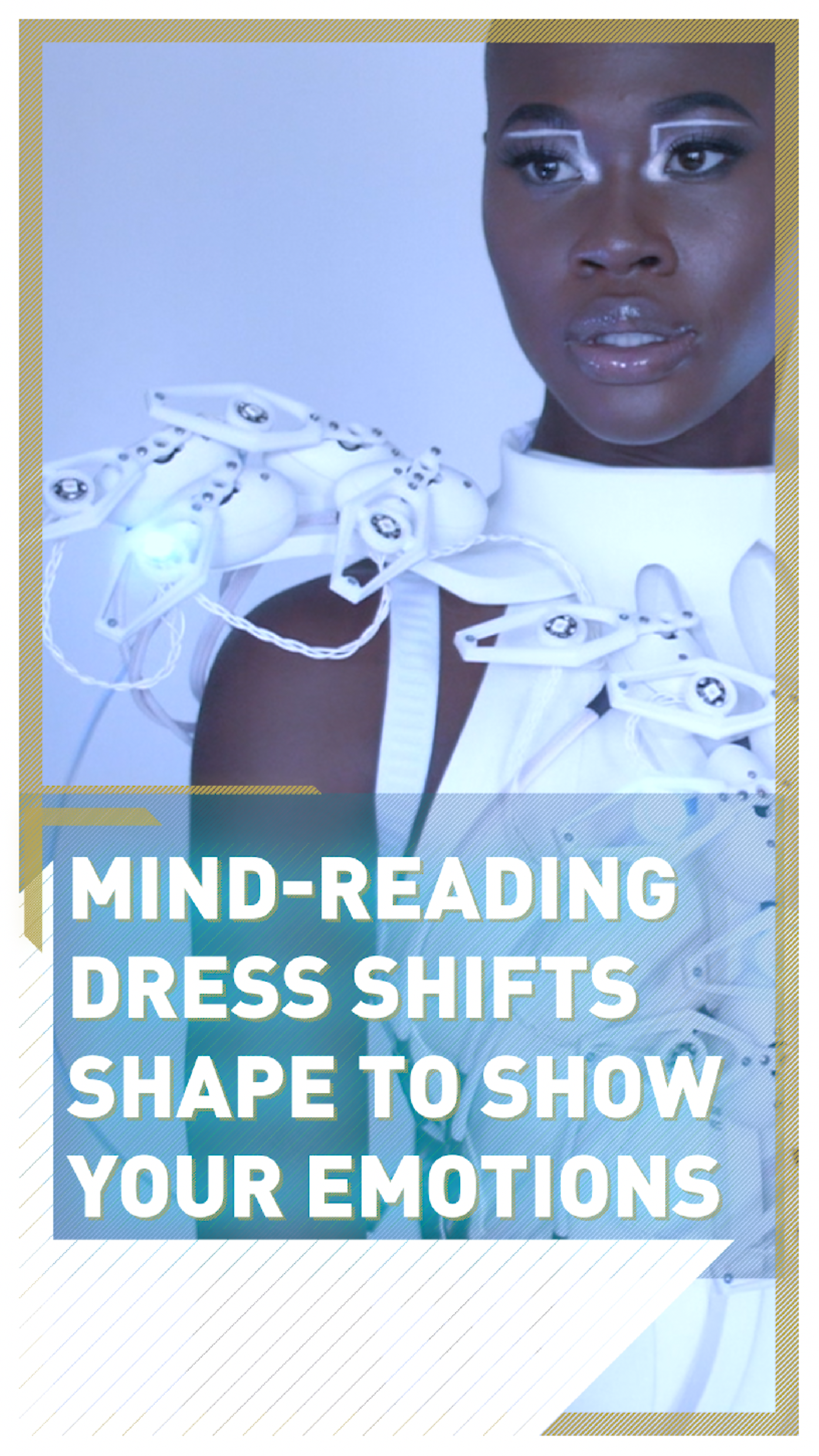

The Pangolin dress is a fashion-fused 3D-printed exoskeleton that can read its wearer's mind and adapt its shape and color to visualize their emotions. /Yanni de Melo

The Pangolin dress is a fashion-fused 3D-printed exoskeleton that can read its wearer's mind and adapt its shape and color to visualize their emotions. /Yanni de Melo

From mood rings to color-changing fabric, couture designers have long attempted to visually express the human condition by fusing fashion with the latest technologies.

But in the case of the Pangolin dress, this drive has been accelerated deep into the 21st century: not only does it have the power to read its wearer's mind - it can also adapt its shape and color to their emotions.

Made up of a 3D-printed exoskeleton connected to the wearer's head through an intricate circuit of scale-like sensors, the futuristic garment analyzes the user's brainwaves in incredible detail.

These are then translated in real-time into a stunning motion-and-light show performed through tiny motors and LEDs built into the cybernetic clothing.

While the dress may be aesthetically breathtaking, it isn't merely a fashion statement: one of the Pangolin's designers, Anouk Wipprecht, tells CGTN Europe the technology is so advanced, it could be used 'to program a prosthetic arm based on whatever you're thinking and seeing."

But how exactly can a dress read someone's emotions, and can fashion-tech truly make the leap from the catwalk to applied medical science?

02:59

From mind to motion

Wipprecht explains the Pangolin dress is based on what is called a brain computer interface (BCI), a device used for measuring the brain's electrical signals.

"That's basically the input in this situation," says the fashion-tech designer. "And the dress functions as the output, so it's visualizing what is happening in the brain."

Showcased in September at the Ars Electronica Festival in Austria, the dress's ultra low energy and high resolution BCI was developed by Wipprecht's collaborators, researchers and neuroscientists from Johannes Kepler University Linz and the medical engineering company g.tec.

Connected to the head through a grid of diamond-shaped printed circuit boards, the BCI's sensors are attached to the bare scalp.

"You need to have a shaved heads for this in order to connect directly to the skin," the designer explains, adding that it took a while to find a model with no hair to showcase the dress.

The Pangolin's brain computer interface uses a massive 1,204 individual electrodes to read the wearer's brainwaves. /JKU Linz Institute of Technology, Institute for Integrated Circuits.

The Pangolin's brain computer interface uses a massive 1,204 individual electrodes to read the wearer's brainwaves. /JKU Linz Institute of Technology, Institute for Integrated Circuits.

The consequent distinctive visual effect is what inspired the designers to name the dress after the pangolin, a type of anteater found in Asia and Africa.

"If you look at the brain computer interface, we created these little sections and each section almost looks like scales," says Wipprecht, adding that from a mechanical perspective, the pangolin's armor was a fascinating concept to develop.

Wired up to 32 Neopixel LEDs and 32 servo motors dotted about the 3D-printed garment, the BCI gives a detailed reading of the wearer's brain patterns, mirroring them in light and motion.

If the wearer is in a more meditative state, the lights simply glow a warm purple, but if brain activity is intense, the dress's angel-like wings extend and the LEDs flicker blue.

The dress was named after the pangolin, a type of scaly anteater found in Asia and Africa. /Deon De Villiers/VCG

The dress was named after the pangolin, a type of scaly anteater found in Asia and Africa. /Deon De Villiers/VCG

Because it is carrying so many of these devices, one of the potential problems for the designer was going to be the dress's excessive weight.

But by employing an innovative 3D printing technique called selective laser sintering where lasers are fired into soft material to bind it into a solid structure, Wipprecht was able to use a lightweight nylon substance to reduce the burden, making the dress strong enough to carry the tech but light enough to be worn.

"We can look at this data on the computer," says the designer. "But I think it's much more fun to see it happening on the body."

Read more: How will COVID-19 change the fashion industry?

If the Pangolin's wearer is in a more meditative state, the lights simply glow a warm purple, but if brain activity is intense, the dress's angel-like wings extend and the LEDs flicker blue. /Yanni de Melo

If the Pangolin's wearer is in a more meditative state, the lights simply glow a warm purple, but if brain activity is intense, the dress's angel-like wings extend and the LEDs flicker blue. /Yanni de Melo

How can a dress read someone's emotions?

One of the Pangolin's most distinguishing features is how incredibly sensitive its brain computer interface is.

This is in part because of the large number of sensors used: a massive 1,204 individual electrodes, separated into 64 groups of 16 channels, all brought together through the scaly grid mounted on the head.

"Usually, we tend to work with – especially with more commercial devices – only a few electrodes," says Wipprecht, who has been creating garments built around BCIs since 2009.

Average surface brain circuit interfaces usually only use 64 electrodes, enough to show if a brain wants to move a left or a right arm, but the Pangolin's 1,204 sensors makes it much more sensitive. /JKU Linz Institute of Technology, Institute for Integrated Circuits

Average surface brain circuit interfaces usually only use 64 electrodes, enough to show if a brain wants to move a left or a right arm, but the Pangolin's 1,204 sensors makes it much more sensitive. /JKU Linz Institute of Technology, Institute for Integrated Circuits

Average surface BCIs usually only use 64 electrodes, enough to show if the brain wants to move a left or a right arm, but not enough to pick up signal to move something smaller, like a finger.

Detecting anything more detailed usually requires an implant, but because the Pangolin's custom built chips are so low energy, they could afford to use more.

"If you want to see the whole fluctuation of the full brain... you do need to have more access points," she adds. "The more channels you have the more resolution you have, so the more we can understand about the brain."

Watch: Fashionable upcycling: Turning trash into trends

The more channels a BCI has, the better the resolution and the more can be understood about the brain. /JKU Linz Institute of Technology, Institute for Integrated Circuits

The more channels a BCI has, the better the resolution and the more can be understood about the brain. /JKU Linz Institute of Technology, Institute for Integrated Circuits

Cyborg potential

The next stage was for the neuroscientists from G.tec to use machine learning to collate and interpret the information, building up a picture of what the wearer's brain does as it thinks about performing a physical motion.

Because different brains have different patterns, artificial intelligence was used to tailor the dress' system to the specific user, learning the unique signals sent from the brain to the body to make it move.

And because the resolution is so high in the Pangolin dress, "you can almost only think of moving a finger and you can already detect that using the BCI," says Wipprecht.

"We are able to program a prosthetic arm based on whatever you're thinking and seeing," she adds.

'Technology comes into our life to help us but at one point in time it might have stopped and it might have started to stress us out,' says designer Anouk Wipprecht. /Yanni de Melo

'Technology comes into our life to help us but at one point in time it might have stopped and it might have started to stress us out,' says designer Anouk Wipprecht. /Yanni de Melo

That means the technology could be developed for the medical industry for people who are paralyzed or have missing limbs, and there's even the chance of creating an exoskeleton controlled completely by a BCI system.

Wipprecht is already using similar tech to help children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to better understand how their brains work, while her collaborator Christoph Guger, the co-founder of G.tec, is using BCI systems to help with stroke rehabilitation.

The team now wants to find a way to make the dress wireless without losing any of its resolution or speed, while Wipprecht is considering how to make its visual performance even more spectacular.

Wipprecht wants to use the intersection between science, tech and fashion explored in the Pangolin to realistically represent our emotions. /Yanni de Melo

Wipprecht wants to use the intersection between science, tech and fashion explored in the Pangolin to realistically represent our emotions. /Yanni de Melo

"Technology comes into our life to help us but at one point in time it might have stopped and it might have started to stress us out," says the designer.

She points out that the majority of our devices have no idea what's going on inside our heads are not listening to our body: "My mobile phone is not listening to my body, so it doesn't know when I'm stressed."

Wipprecht wants to use the intersection between science, tech and fashion explored in the Pangolin to try and truly represent our emotions and believes that she's not alone in the pursuit: "I think a lot of people are interested in ... stepping into that notion of technology that can really feel with us almost, whether that is a dress or a device."

For the designer, "it really speaks to people when fashion and technology gets combined ... it's communicating something of us."

She says: "If it's connected to the body and it's connected to the surroundings – the things that are happening around us, then it really comes alive."

Video editing: Ben Wildi