02:21

WATCH: Iolo ap Dafydd meets some of the Kherson locals fighting to recover

Outside the city, at a sturdy looking checkpoint, we're told to pull over. A heavily armed soldier walks over and asks for our media accreditation. Carefully he photographs each one individually. He doesn't seem enamored that more journalists are trying to enter Kherson.

The sun is hot, and the rough tarmac near our vehicle is melting. It could be a metaphor for the city.

Kherson was 'liberated' from the 'occupiers' as most Ukrainians refer to land that's been re-taken since Russia's so-called special operation began in February last year. Liberation has become an important word here. And like 'war', 'invasion', 'occupation' is heavily loaded.

On 9 November last year, the Ukrainian Army re-took control and the Russians left to cross the river, from where they still fire barrages of shells into the city most days.

Eventually we're allowed to go with a wave of a hand. For the next few kilometers, we drive down wide roads and enter the city's leafy boulevards. You notice immediately that it's empty. Empty of cars, empty of people. Empty but not quiet.

In the distance, Ukrainian artillery rumbles as outgoing fire tries to dislodge Russian positions on the left bank of the now much drier Dnipro river.

Iolo ap Dafydd has been speaking to some of those desperately trying to rebuild their lives and city./ CGTN Europe

Iolo ap Dafydd has been speaking to some of those desperately trying to rebuild their lives and city./ CGTN Europe

The port in Kherson and the streets closest to the river were flooded after the Kakhovka Dam upstream, was partially demolished in June. The explosion allowed the full reservoir to drain and flood large areas of this region, before the surge drained into the Black Sea.

Slowly we drive down a hill towards Tchaikovsky Street - an area that wasn't affluent before the conflict began. Now it looks and smells even worse. I met Yevhen Kulishov. A tall smiling man in his 40s. He's part of a team of volunteers who help locals clean their houses.

"After the explosion of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant, our organisation," he says, "created a coordination headquarters and gathered volunteers."

READ MORE

Zelenskyy says election possible; Kremlin rejects grain deal hope

Ukraine recaptures territory, Russia foils attack on Crimea

Russia warns that giving Ukraine F-16 jets will escalate conflict

He helps teams do all kinds of work - and he lists them:

"I coordinate teams with the aftermath of the damage, pumping out water, helping people to remove rubble, taking out silt, removing destroyed furniture, walls and all that, everything that is destroyed."

Middle aged men stripped to their shorts, brown from the sun, are cleaning plaster and debris from houses which were three meters under water. The dry summer helps with the cleaning, but not the odors.

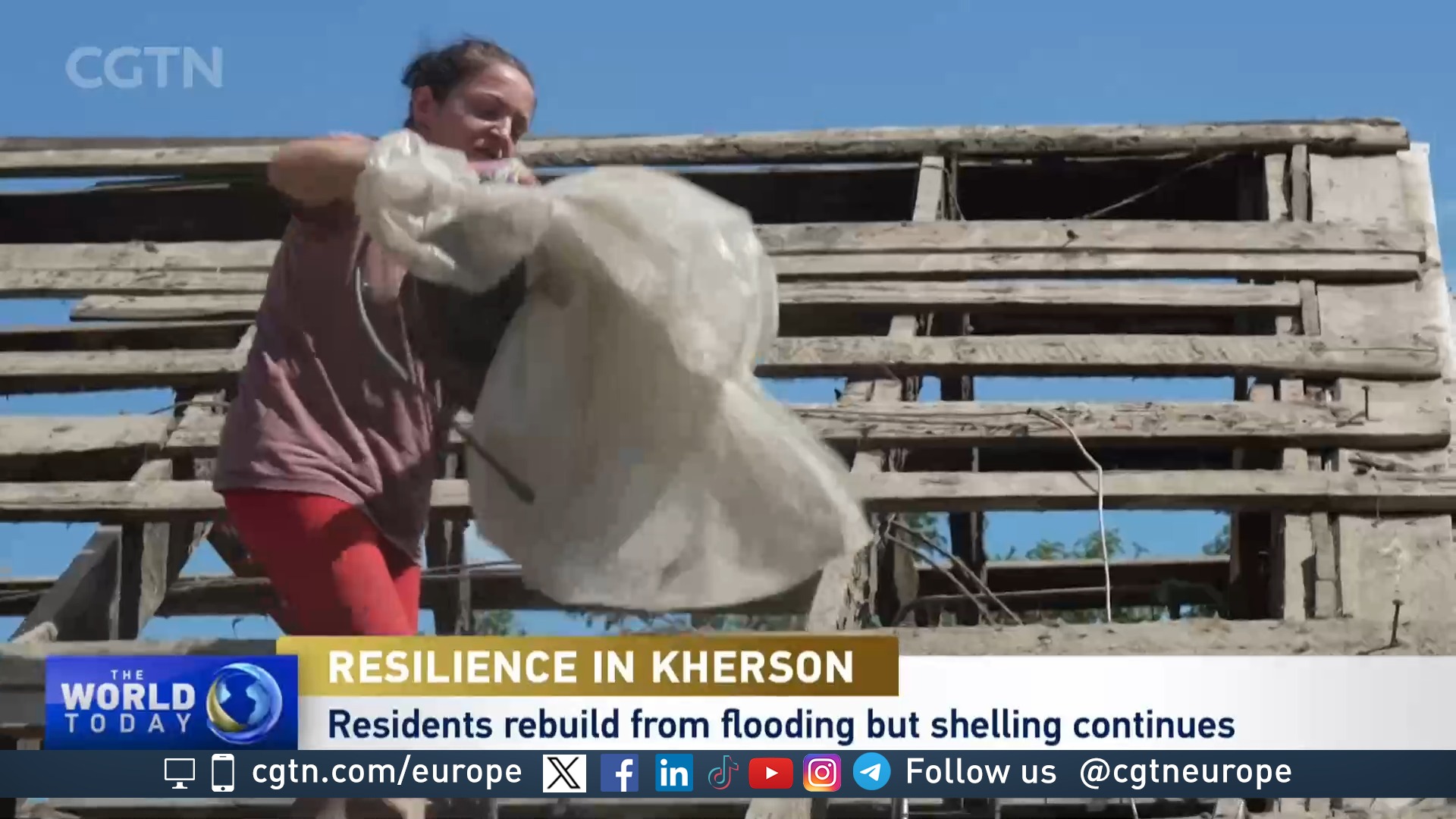

Lidia Pudgabiuk is stripping insulation from the roof of her former home. When she climbs down a ladder she said defiantly: "Nothing scares me anymore. What scares me is that I have no place to live, that I have a small child, and I have no place to live. We are currently renting an apartment in Kyiv."

Lidia Pudgabiuk says not having a house is the only thing that frightens her now./ CGTN Europe

Lidia Pudgabiuk says not having a house is the only thing that frightens her now./ CGTN Europe

Her eight-year-old son is in Kyiv, while her husband fights somewhere along the 1,000-kilometer line between the Ukrainian and Russian forces.

Three doors down, in another swelteringly hot wreck, Olena Checkun wears a peaked cap to shield her eyes from the sun. Like her neighbor, her home, the family business of repairing cars and the garden are destroyed.

What can be salvaged is laid out - but the biggest pile is the one outside her front gate. As with the rest of the street, those piles are furniture, clothes, belongings that have to be thrown away.

Olena describes how the ceiling fell in on her house, and how the walls have to be stripped back to the brickwork. The old-style plaster of soil and straw is useless and lies in piles across most rooms.

She adds: "The furniture was destroyed in every room; nothing was left. The shed collapsed and we made a hole in the garage to try and repair a car, but we didn't finish it and it collapsed."

Inside her garage is a rack to lift a car, so a mechanic could work underneath it. The car that was there before the flood, remains. It partly hangs precariously but will eventually have to be hauled down.

Most of the street is eerily empty. Not because of the flood waters and its damage, but because of constant shelling.

A few hundred meters away there's an island in the river. It's large enough to be connected by a concrete bridge, and to hold a number of high apartment blocks and a smaller suburb of private houses. As soon as we cross the bridge at high speed, we're stopped at another checkpoint.

Sullen soldiers check our passes. "It's dangerous," says an officer and calls his superiors to check if we should be allowed to pass. After a nervous few minutes, we get clearance. We go. Again, as fast as we can to follow Yevhen Kulishov around the battered part of Kherson. It was a river port city once home to almost 300,000 people, but now is home to a fraction of that.

Oleksandr Prokudin, head of the Kherson Regional Military Administration says: "This region has three main problems ; the Russians who are destroying our city from the opposite bank of the river as they constantly shelling.

"Secondly, de-mining. The area is densely littered with mines. Thirdly, the reconstruction and a return to normal human life for the people of Kherson."

Two dangerous tasks have to be dealt with now, but the much more laborious work of re-building Kherson could take decades; and cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

Subscribe to Storyboard: A weekly newsletter bringing you the best of CGTN every Friday