04:53

· The United Nations' climate agency urged countries to strengthen their 2030 targets by 2022 in a draft of the political decision to be agreed on by the end of COP26.

The new timeline would require countries to submit their updated emissions three years earlier than previously planned. According to the 2015 Paris Agreement, countries had to submit their plans every five years and the last deadline was 2020.

The move is in part because vulnerable countries argued the 2025 deadline was too far in the future to cut emissions in time to avoid disastrous global warming.

The current version asks countries to "revisit and strengthen the 2030 targets in their nationally determined contributions, as necessary to align with the Paris Agreement temperature goal by the end of 2022."

It also set a goal to reach net-zero emissions by around 2050 and called on more financial support for developing countries beyond the initial pledge of $100 billion.

And for the first time, it asked countries to phase out both coal and subsidies for fossil fuels.

But despite this, environmental groups and scientists have criticized the draft for not going far enough.

"This draft deal is not a plan to solve the climate crisis, it's an agreement that we'll all cross our fingers and hope for the best," said Jennifer Morgan, the international director of Greenpeace. "It's a polite request that countries maybe, possibly, do more next year."

Negotiators from more than 200 countries will debate the draft over the next three days before finalizing it on Friday.

A group of protesters at COP26 on November 10. /Reuters/ Yves Herman

A group of protesters at COP26 on November 10. /Reuters/ Yves Herman

· Another report published by the Climate Action Tracker (CAT) on Tuesday also argues that national pledges are not enough to keep temperatures from increasing well above pre-industrial levels.

The report says current 2030 targets, excluding long-term pledges, will put global warming on track to reach 2.4 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century.

"Even with all new Glasgow pledges for 2030, we will emit roughly twice as much in 2030 as required for 1.5 degrees Celsius," the report said.

"Therefore, all governments need to reconsider their targets."

In its most "optimistic scenario," temperatures would increase 1.8 degrees Celsius by 2100, but only "if all the announced net-zero commitments or targets under discussion are implemented."

And it added that "it's a big IF. Our analysis shows countries with an 'acceptable' net-zero rating cover only 6 percent of global emissions."

A group of people gathering around a puppet of a young Syrian refugee girl at COP26. /Reuters/ Phil Noble

A group of people gathering around a puppet of a young Syrian refugee girl at COP26. /Reuters/ Phil Noble

· Coal is not being phased out fast enough, according to the CAT report.

The report argues that to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, coal needs to be phased out by the OECD's 38 members by 2030.

And the rest of the world needs to phase it out by 2040.

But despite this, several OECD countries, such as Japan, South Korea and Australia, plan to still be using coal for their energy generation in 2030.

And while the UN's draft agreement did call on phasing out coal globally, it did not set a timeline for countries to do so.

· One of the promises to come out of COP26 is a Global Methane Pledge to cut emissions by 30 percent by 2030.

More than 100 countries have agreed to this goal, and it could have an almost immediate effect on global temperatures rising.

That is because Methane only stays in the atmosphere for around 12 years, while carbon dioxide sticks around for hundreds of years.

But the report claimed that, while important, this cut won't greatly impact their previous predictions because many existing national targets already included this Methane reduction.

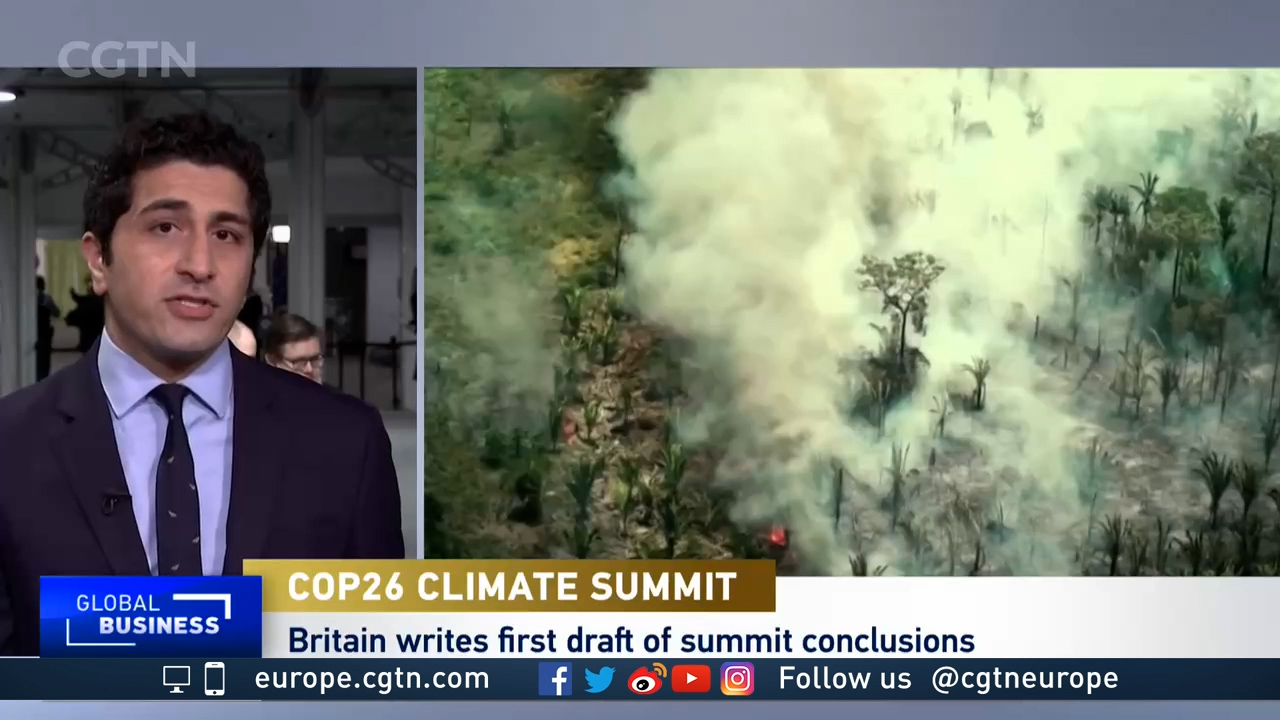

· On Monday, more than 100 leaders agreed on a pledge to reverse deforestation and land degradation by 2030. The Global Forestry Finance pledge was underpinned by a promise of $19 billion in funds for countries to protect forests.

But while the report agreed that this pledge could "result in additional climate mitigation," it is unlikely to do so because it requires funding on top of the already promised $100 billion to developing countries.

And that target has yet to be met.