02:24

Throughout much of the pandemic so far, many eyes have been focused on the English city of Oxford. Scientists there had been racing to develop a vaccine they hoped could one day provide a path to herd immunity, not just for the UK but for billions of people across the world.

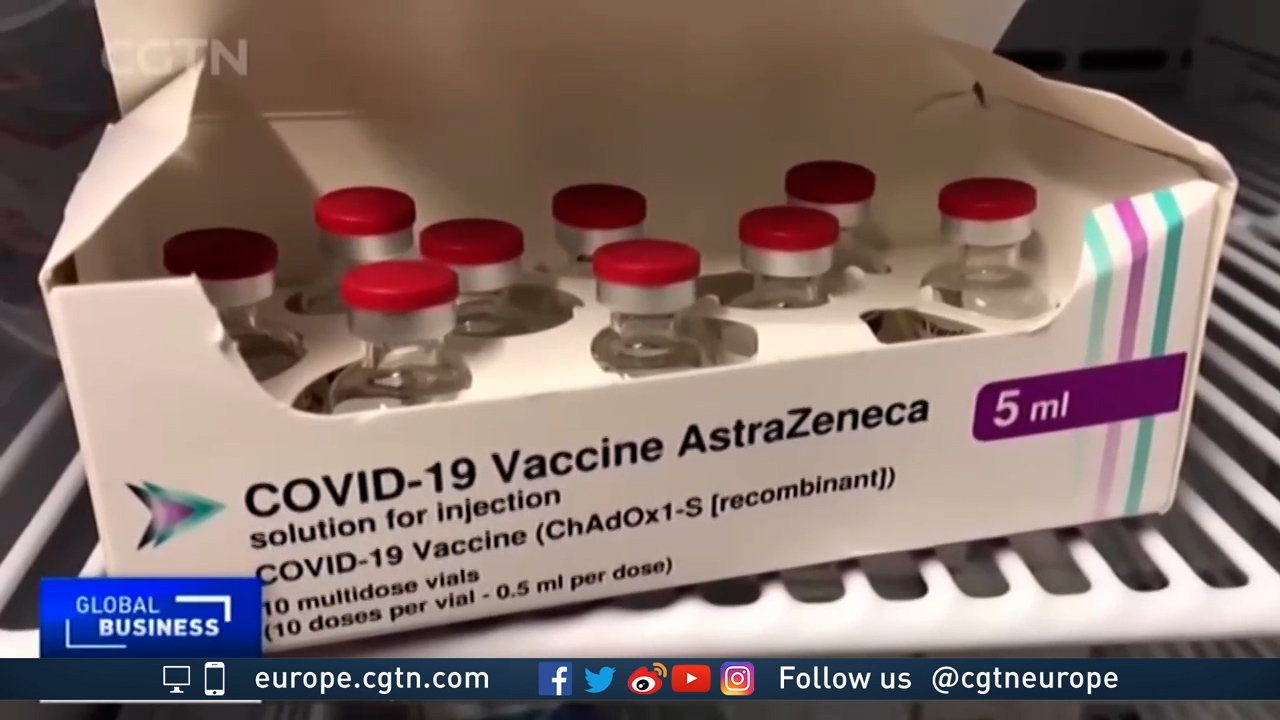

Development of the Oxford University-AstraZeneca vaccine progressed at unprecedented speed. But then something unexpected happened. Regulators found data on the jab's efficacy, specifically in older people, was not as robust as other leading vaccine candidates. Ultimately, another one, developed by BioNTech/Pfizer, began its UK roll-out first.

But the Oxford vaccine remains the UK's biggest hope and perhaps the world's. Approved in the UK in early January, its roll-out is now well under way. Some 530,000 doses have been made initially available to the country. The British government has pre-ordered 100 million in total.

"Early data indicate it also works in the older age group," says Arne Akbar, a professor of immunology from University College London.

And further evidence will be collected much more rapidly from now on, given the growing number of vulnerable people receiving it. There is a growing sense of optimism among experts that such data will go further in confirming its effectiveness in those groups. Earlier phase one and two trials had already concluded it was safe.

The UK was one of the worst-hit countries in the world during the first wave last spring. This winter, it is being hit even harder as a new, more contagious, variant of the virus sweeps across the country.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson wants the UK to be the first country in the world to fight back by vaccinating its entire population. It is aiming to administer nearly 14 million vaccinations to vulnerable groups by the middle of February.

The UK enjoys some logistical advantages in supporting such an ambitious vaccine program. It has a National Health Service, is geographically relatively small and well-connected and the vaccine it plans to use most widely is produced – as well as developed – domestically.

That is not unique. A handful of other countries and regions including China, the European Union, India and the U.S. also have significant vaccine manufacturing capacity. But "it will help tremendously," says Akbar.

CLICK: STEM CELLS AND ELECTROMAGNETIC-BLOCKING UNDERWEAR: THE SECRET TO LONGEVITY?

The other UK-approved jabs so far are from Moderna and BioNTech/Pfizer. Both use a first-of-its-kind technique that essentially sends a message to the recipient's immune system, teaching it to recognize and fight coronavirus infection.

Both mRNA vaccine types are for now far less stable, however, requiring super-cold storage and special packaging that makes it more difficult to scale up. There are also only a limited number of production sites that have the right expertise and equipment at hand.

That may change in time, says Zoltan Kis from the Future Vaccine Manufacturing Hub at London's Imperial College. Imperial scientists are developing an RNA molecule that self-multiplies, meaning each dose would need a far smaller amount of it. "The technique itself is not the main obstacle," says Kis, "it is mass production that presents the challenge."

That's something even the founder of BioNTech, which partnered with U.S. giant Pfizer, admits.

"We will try to produce more vaccine doses in 2021 but we don't know if this is possible at the moment," Ugur Sahin said in December. "We will have an understanding if we are able to increase and how much at the end of January."

Another advantage for the Oxford University-AstraZeneca vaccine is cost. It will be sold at no profit for the duration of the pandemic, at between $3 and $4 per dose, although it is worth noting AstraZeneca has not said publicly what its cost of production per dose is. Still, Pfizer's jab is thought to come in at around $20. Moderna is charging between $32 and $38 per dose.

The technique used to make the Oxford vaccine helps in terms of its global appeal, too. It is developed by taking a harmless virus and modifying it in a way that produces an appropriate immune response to fight SARS-CoV-2. The finished product is more stable and can be stored and transported in a standard fridge.

In developing countries without as much access to specialist storage facilities, that is far more appealing. The plan is to roll-out up to 3 billion doses in 2021 globally.

The main potential drawback is one that will affect every vaccine on the market.

"All vaccines – and non-vaccines, including other injectables – are filled into these vials using the same type of filling lines. And there is a limited global capacity of these filling lines," says Kis.

UK officials are already warning this could throw their ambitious plans off track. But as the UK enters its darkest days of this pandemic so far, the Oxford University-AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine remains its greatest hope.