Rewilding – the large-scale restoration of ecosystems long gone or damaged due to human activities – is all about letting nature do its thing and take care of itself.

"It's about the comeback of natural processes, the comeback of species," explained Deli Saavedra, regional manager for Rewilding Europe, when CGTN Europe met up with him last year.

We followed Saavedra and his colleague Serban Ion through the reclaimed wilderness of the Danube Delta, where they were chasing traces of the Eurasian beaver's return to the region.

03:05

The Eurasian beaver had disappeared from the Danube Delta – Europe's largest natural wetland, extending across the borders of Romania, Moldova and Ukraine – more than 200 years ago, when they were hunted to extinction in Romania and to near-extinction across the continent.

Their spontaneous return to the region was a reason to celebrate for Saavedra and all those working to rewild the river delta, as the beavers' ingenious damming allows many other animals to thrive in the same ecosystem.

If you put all the pieces back into the ecosystem and you have a nice complete ecosystem, let's be relaxed about what nature is doing

- Deli Saavedra, Rewilding Europe

In a year during which all sorts of human activities were thrown off their normal tracks by the COVID-19 pandemic, what happened to the rewilding of the Danube?

The Eurasian beaver is considered an "ecosystem engineer". /VCG

The Eurasian beaver is considered an "ecosystem engineer". /VCG

Understandably, the coronavirus crisis stopped or delayed some rewilding projects planned for this year, but the work started last year continued to bear fruit.

"We have especially seen progress in the impact of the last herbivores that we have introduced into the ecosystem, especially in some areas of the new Delta – with the buffalo, the horses and also the kulan starting to make an impact into the ecosystem, opening areas and giving more space for biodiversity," said Saavedra, who is currently working from home in Catalonia, Spain.

Without firsthand knowledge of what's happening by the Danube Delta, Saavedra mostly has to rely on the information passed on by the locals.

Unfortunately the beavers seem to still be quite elusive. "I really would like to have more news about the beavers, after one year," says Saavedra. "If those families are still there, if they are increasing.

"Some fishermen say that they're still there, but we don't have really new and good information about numbers, about the expansion of the species."

The kulan horse's comeback

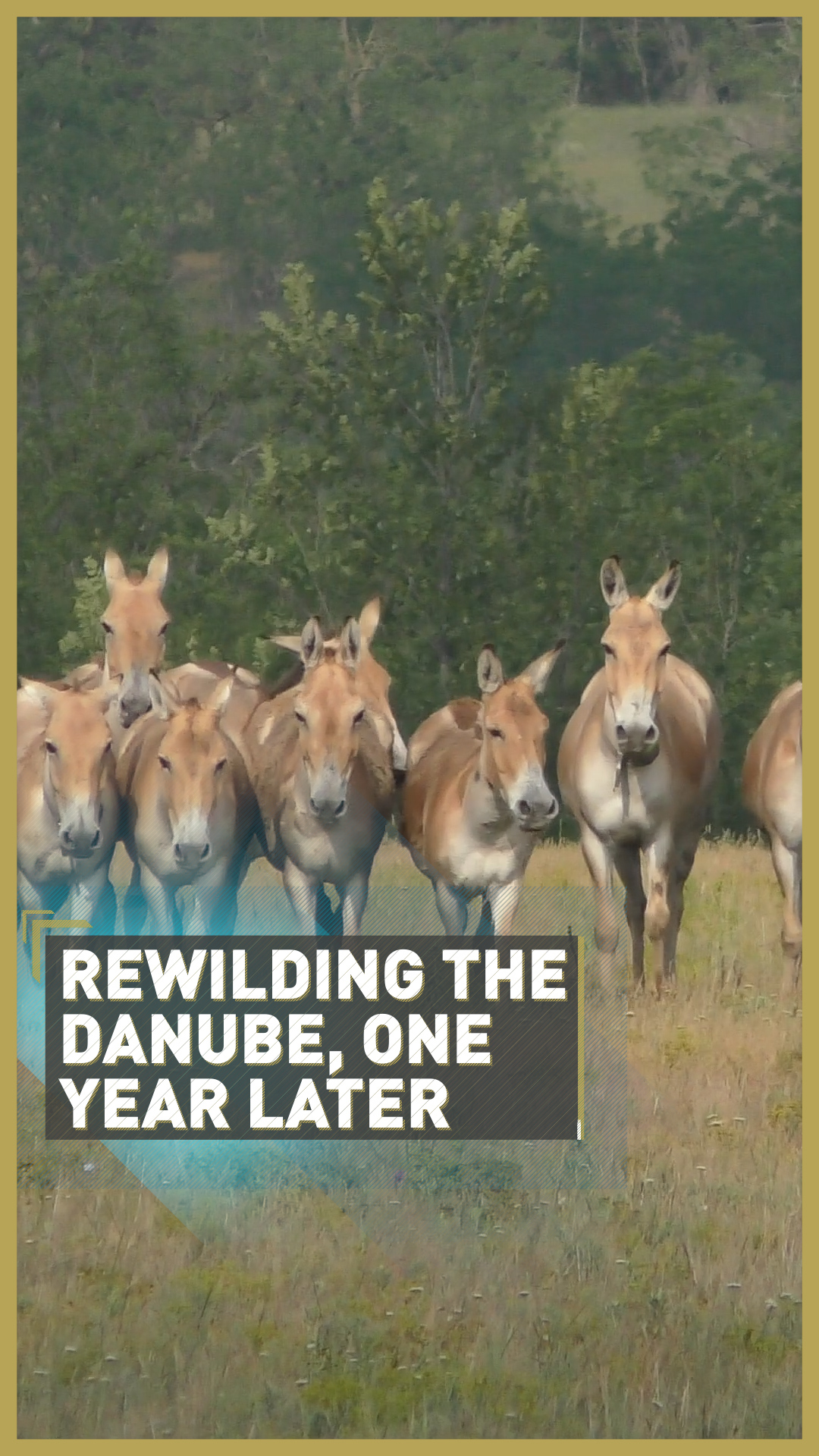

What we know instead is that the reintroduction of the kulan horses, started in May this year, has already produced encouraging results for the delta's ecosystem.

"Large heavy horses – and the kulan is one of them – are what we call 'architects of nature'," explains Mykhailo Nesterenko, executive director of Rewilding Ukraine.

The herd of kulan horses roaming free in the Danube Delta after being reintroduced to the area in May 2020. /Rewilding Europe

The herd of kulan horses roaming free in the Danube Delta after being reintroduced to the area in May 2020. /Rewilding Europe

By grazing, the kulan – a wild relative of the domesticated donkey – creates the perfect environment for other small animals, for example allowing small birds such as the skylark to nest.

The kulan, like the Eurasian beaver, had disappeared from the region around 200 years ago. "The kulan is a species that was living in the big steppes, big grasslands that were going from Hungary all the way to Kazakhstan," says Saavedra.

"These bigger steppes disappeared because of farming in the last centuries, and now the biggest species are in Kazakhstan, in Mongolia. But there's a very small piece in Ukraine, close to the Danube Delta. And in this area, we want to restore the ecosystems."

Twenty horses, brought originally from Turkmenistan to the Askania-Nova natural reserve in Ukraine, have been reintroduced to the Danube Delta region over the past year.

"The experts from Askania-Nova believe that by the end of the project in three to four years, we should have around 50 animals," says Nesterenko. "We will see how successfully they establish themselves and how fast their population will grow.

"There are predators in the area, like wolves, that prey on kulan – but kulan are very sturdy animals, they're quite well able to defend themselves. So we will see how they will fit into the animal world and ecosystem."

Eagle owls fly over the Danube once again

Also establishing themselves in the delta are eagle owls, who are being reintroduced to the Danube as an ongoing process. The first eagle owl chick – originally bred in the Odessa Zoo – was released in spring 2019 and was followed in July 2020 by the release of three more juvenile eagle owls.

"Of course, four animals are not making a population, we need to continue the process for the next few years," says Saavedra. "But the ones that we have released, they are doing okay."

The three juvenile eagle owls born in the Odessa Zoo before being released in the Danube Delta in July 2020. /Rewilding Europe

The three juvenile eagle owls born in the Odessa Zoo before being released in the Danube Delta in July 2020. /Rewilding Europe

Thanks to trackers attached to the birds, Saavedra and his team are able to tell how the owls are settling down in the new environment.

"We know that one of those animals is left of the Danube Delta and is more to the north in some big lagoons, probably hunting rats or maybe even ducks, we don't know exactly, but they are doing okay."

Rewilding Europe expects to keep releasing three to four new chicks bred in European zoos every year to the Ukrainian section of the Danube Delta to restore the population in the area.

What does the future hold for the Danube Delta?

As the pandemic unfolded this year, Saavedra had hopes it could prompt people to change their behavior and realize we need to act now to fight climate change. But he was soon disappointed when he saw that after lockdown, most people went back to "business as usual."

Biodiversity will be key to resisting climate change, according to Deli Saavedra. /Rewilding Europe

Biodiversity will be key to resisting climate change, according to Deli Saavedra. /Rewilding Europe

"Imagine that you are staying on the beach and you are surfing the big wave, but the big wave, which is the pandemic, is very small compared with the new wave that is coming, which is the climate breakdown, the biodiversity crisis. That's the real challenge," he says.

"If we want to have biodiversity, you need to have these keystone species that are creating different habitats, different diversity. In fact, you want to have wildlife. Because with wildlife, you have biodiversity. We have biodiversity, the diversity of habitats. Then you have resilience. And we need this resilience against climate change.

"If everything is exactly the same, it will be affected exactly the same way. If you have different things that are completely different, climate change or other causes are going to affect maybe one piece, but not everything, because we have a biodiverse environment. And this is exactly what we want with rewilding."