02:51

It was once Britain's best-kept secret. A cluster of unassuming huts inside a country estate in central England, where a group of codebreakers, mathematicians and military personnel worked around the clock to decrypt enemy messages during World War II.

Bletchley Park in Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, was one of the most successful Allied intelligence operations, providing valuable input that not only saved countless lives but also changed the outcome of critical events during the course of the conflict.

Known by several different aliases like 'Station X' and 'B.P.', the estate was bought in 1938 to relocate the Government Code & Cypher School (GC&CS) and the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) after warnings that London might become a target of heavy air attack in a future war.

Over the next few months, as the prospect of war with Germany grew, the first wooden huts were built and communications channels established. The GC&CS finally moved from London in August 1939.

By 1945, some 9,000 people were employed at Bletchley Park and its associated outstations.

A group of codebreakers, mathematicians and military personnel worked around the clock at 'Station X' to decrypt enemy messages. /Bletchley Park Trust

A group of codebreakers, mathematicians and military personnel worked around the clock at 'Station X' to decrypt enemy messages. /Bletchley Park Trust

Peronel Craddock, head of collections and exhibitions at Bletchley Park Trust said: "Early in the war, the operation centered on the work of a small group of experts.

"By 1943, Bletchley Park had developed from a small community of specialist cryptanalysts into a vast and complex global signals intelligence factory."

As the war progressed, signal intelligence (SIGINT) grew in scale and sophistication and so did the urgency to rope in the sharpest of minds.

A new crop of code-readers was recruited to decipher messages that were being exchanged by the Axis powers.

The Wehrmacht – German armed forces – were using the Enigma, an electro-mechanical cipher machine. The Italians and the Japanese later adopted it.

The Enigma contained a series of interchangeable rotors, which turned every time a key was pressed to keep the cipher changing continuously.

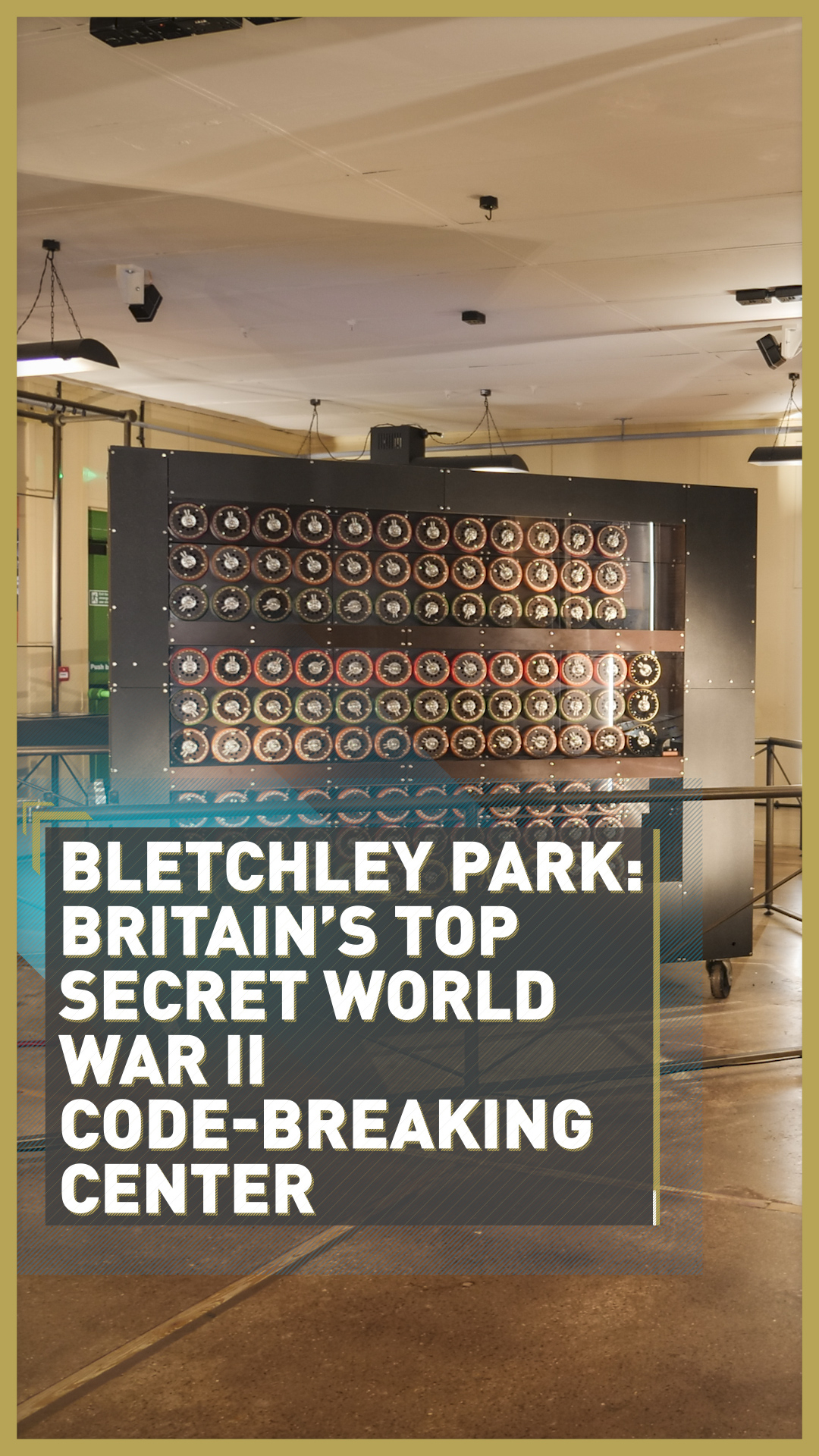

An electro-mechanical device called the Bombe was used by the British to help decipher secret German Enigma messages. /Bletchley Park Trust

An electro-mechanical device called the Bombe was used by the British to help decipher secret German Enigma messages. /Bletchley Park Trust

This was combined with a plugboard in the front of the machine where pairs of letters were transposed. These two systems together offered 103 sextillion possible settings to choose from.

Craddock said: "The Poles had broken Enigma in as early as 1932, but in 1939 with the prospect of war, they decided to inform the British of their successes."

The first wartime Enigma messages were broken at Bletchley Park in January 1940 and continued for the remainder of the war.

One of the greatest coups was the decryption of the Dolphin Enigma by Alan Turing, a Cambridge University mathematician and Gordon Welchman.

The breakthrough helped transatlantic convoys, delivering vital supplies to the UK, evade a wolfpack of roving German U-boats.

Intelligence generated from Bletchley Park was crucial to D-Day when the Allies landed in Normandy, France on 6 June, 1944. /National Archives and Records Administration

Intelligence generated from Bletchley Park was crucial to D-Day when the Allies landed in Normandy, France on 6 June, 1944. /National Archives and Records Administration

Tom Cheetham, a research officer with the Trust, highlighted Turing's contribution.

"He was only one of about 40 university professors and graduates who were recruited at the start of the war but he was certainly the most successful."

But perhaps Bletchley Park's greatest moment came when it gained access to the German strategic ciphers.

More complex, faster and more secure than the Enigma, the messages were encrypted by the highly advanced Lorenz cipher machine.

The ciphers were used to secure communications between Berlin and army commanders in the field. Hence, the intelligence value of breaking into the dispatches was immense.

Bletchley Park's greatest moment came when it gained access to the German strategic ciphers. /Bletchley Park Trust

Bletchley Park's greatest moment came when it gained access to the German strategic ciphers. /Bletchley Park Trust

Initial efforts were successful but as the volume of intercepts increased, the need to mechanize the process was acutely felt.

This led to the development of the 'Colossus', the world's first semi-programmable electronic computer, by Tommy Flowers, a General Post Office (GPO) engineer.

Breaking into the Lorenz ciphers allowed the Allies to obtain unprecedented detail of the German defenses, and to delve into the mind of the enemy, including Adolf Hitler himself.

As D-Day, the invasion of Europe approached, Bletchley Park informed the Combined Chiefs of Staff that the Wehrmacht had taken the bait of Operation Fortitude South.

The estate was bought in 1938 to relocate the Government Code & Cypher School and the Secret Intelligence Service. /Bletchley Park Trust

The estate was bought in 1938 to relocate the Government Code & Cypher School and the Secret Intelligence Service. /Bletchley Park Trust

A diversionary tactic which made the Germans believe that the Allied plan to invade Normandy, it was actually a ruse and the real target was Pas de Calais. The Germans rushed to fortify Calais. To their shock, the Allies landed in Normandy on 6 June, 1944.

The codebreakers were also one of the first to know about Germany's surrender.

At the end of the war, the expertise and knowledge garnered at Milton Keynes was taken forward to the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), currently located at Cheltenham, Gloucestershire.

Former U.S. president and army commander Dwight D. Eisenhower best summed up Station X's contribution when he stated in a letter that it had "saved countless British and American lives and, in no small way contributed to the speed with which the enemy was routed and eventually forced to surrender."

Remember to sign up to Global Business Daily here to get our top headlines direct to your inbox every weekday.