01:26

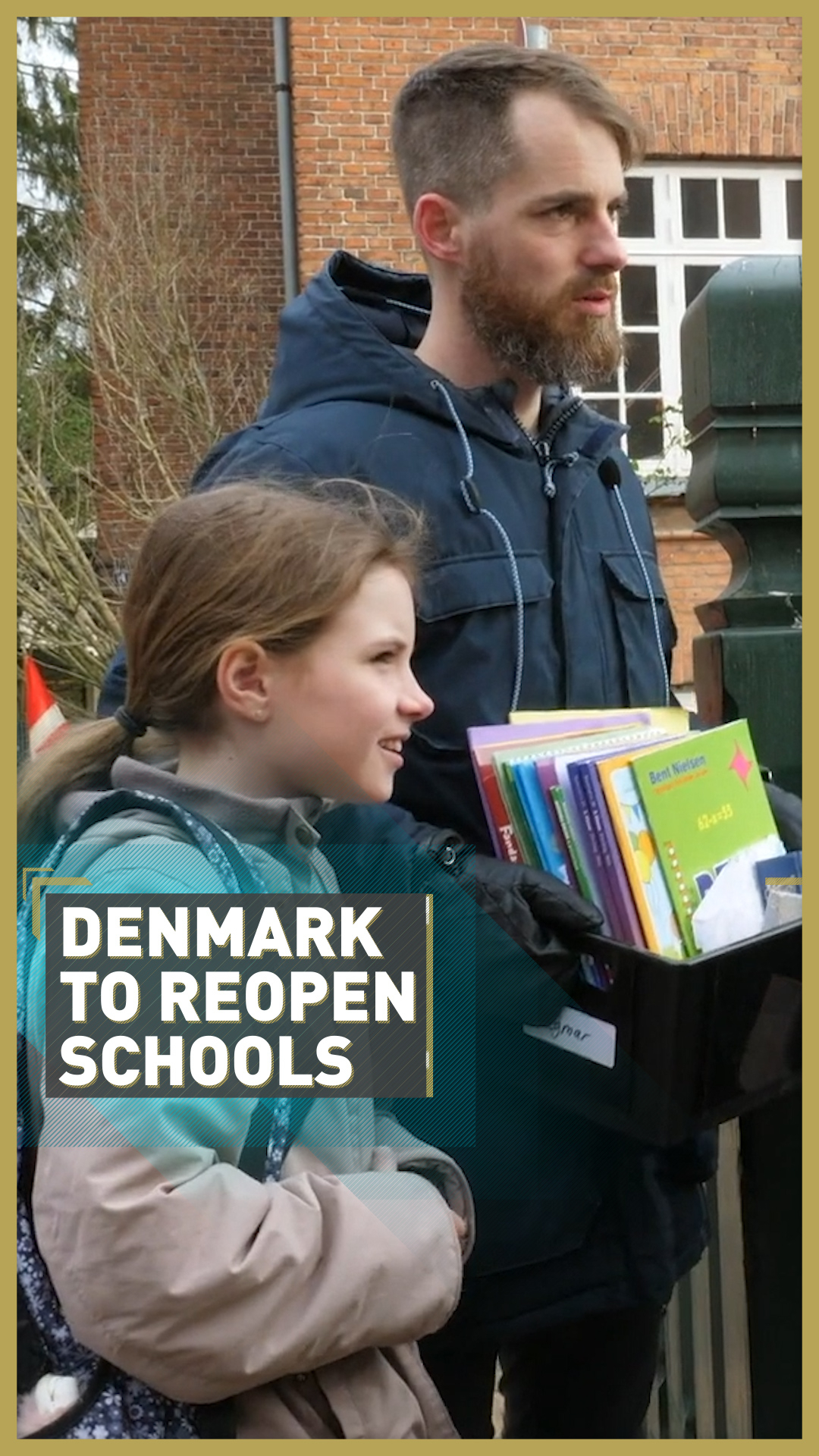

Many Danish students did not return to school on Wednesday. Either the institution itself said it needed more time to put in place the necessary safety measures or parents chose to keep their children away.

Some have joined a Facebook group with some 40,000 members so far, called "My Kid Is Not To Be A Guinea Pig".

There has been some positive responses including those at the Henriette Hørlocks Primary School in the Danish city of Odense, where only five kids were absent out of a total of 300 according to the headteacher.

Outside the school, parents expressed their support for the government's decision, including a doctor. One central argument in favour of this move is that it frees up healthworkers to return to work.

Another is simply that you have to start somewhere. Children do not seem to be nearly as much at risk from COVID-19 as adults.

What has emerged more recently though is evidence that even those with no symptoms could be playing an important role in spreading the disease. That has raised concerns that Denmark's schools could become a breeding ground for a second wave, with parents and teachers therefore at particular risk.

Hørlocks, like any other Danish school, must adhere to strict social distancing and hygiene measures. The hope is that will be sufficient. But of course, no one is certain. Because with this novel coronavirus, very little about what comes next is.

What we do know is that Denmark is seeing its infection rate drop, to the extent where Prime Minister Metter Frederiksen told the nation on Tuesday that restrictions imposed a month ago may start to be lifted sooner than initially expected.

Danish Prime Minister Metter Frederiksen said that restrictions imposed a month ago may start to be lifted sooner than initially expected. /Liselotte Sabroe/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP

Danish Prime Minister Metter Frederiksen said that restrictions imposed a month ago may start to be lifted sooner than initially expected. /Liselotte Sabroe/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP

Neighbouring Norway's is also following suit. The country's kindergartens will re-open on Monday, with primary schools following a week later. Both nations will have an eye across their borders to Sweden though, where some experts now warn its so-far more relaxed approach could be failing, with potentially catastrophic consequences.

The number of deaths in Sweden is continuing to soar. At the moment, Norway has checks in place at its borders while Denmark's crossings are completely closed.

As the crisis unfolded, the rush to introduce such border restrictions caused significant friction between European nations.

On Wednesday, the European Commission called for a more united approach as parts of the continent begin to ease some of their emergency measures in the weeks ahead. But it's clear that each country will also have to move at its own pace, in different ways, to suit its own individual circumstances.

Germany is the latest to announce it will start sending its young people back to school from 4 May. The path back from the peak for those worst affected -- Spain, Italy, perhaps the United Kingdom -- could be far longer, and significantly harder.

All of these measures are experiments without any modern precedent. Governments, their experts, and their citizens overwhelmingly concur that lockdowns cannot go on indefinitely. But the coronavirus has not gone away. And the outcomes of easing them remain riddled with a risk of resurgence.

Remember to sign up to Global Business Daily here to get our top headlines direct to your inbox every weekday