A doctor attends to a patient in intensive care in the COVID-19 ward of the Maria Pia Hospital in Turin. /Marco Bertorello/AFP

A doctor attends to a patient in intensive care in the COVID-19 ward of the Maria Pia Hospital in Turin. /Marco Bertorello/AFP

The statistics are clear, as far as they go. The reasons, less so.

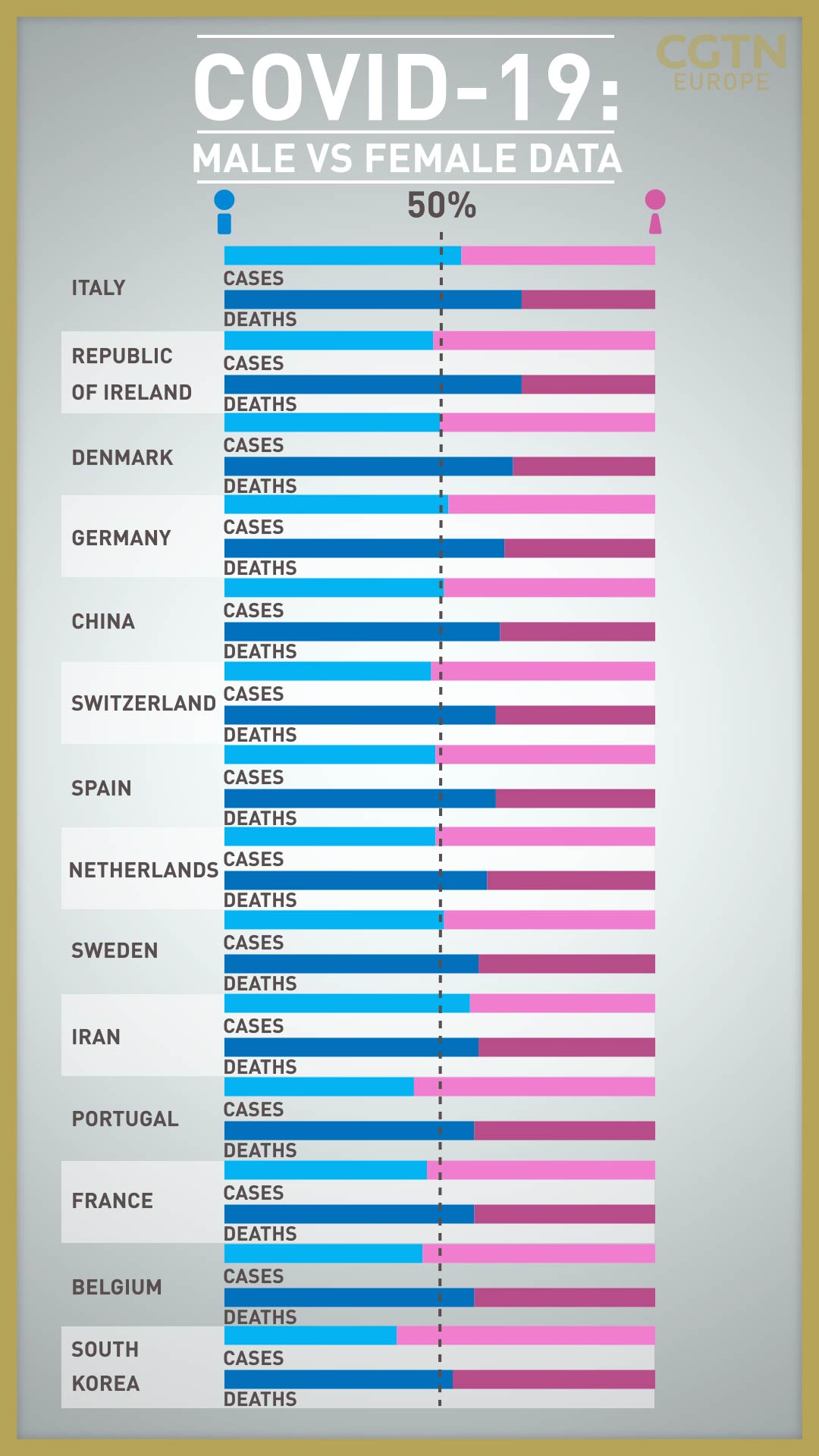

More males infected with COVID-19 die from the virus than females. It's true in Belgium, China, Denmark, France, Germany, Iran, Italy, Portugal, Ireland, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

Out of the more than 200 countries and regions hit by the disease, however, those are among the few that publish gender breakdowns of cases or deaths.

00:18

Why COVID-19 kills males more frequently than females has become a subject of intense debate among scientists.

Data aggregated from official sources by UK-based World Health 5050, which advocates for health equality, shows that in China, while 51 percent of cases were male and 49 percent female, 64 percent of deaths were male compared with 36 percent female.

When they first noticed it, researchers considered the fact that Chinese men smoke much more than women as a possible cause.

But in Ireland, where men were almost two-and-a-half times as likely as women to die from COVID-19, they were only slightly more likely to be smokers. In Italy, the theory didn't match the statistics either, so there were clearly other reasons as well.

Other underlying factors, such as the tendency of men to be heavier drinkers, to suffer more from heart disease and high blood pressure and even that they don't wash their hands as often have also been mooted. Those produce what doctors call "comorbidities," or factors that worsen the impact of the disease.

But there may also be a more fundamental genetic link. The genes that code for the body's immune response sit on the X chromosome. Females have two X chromosomes but males have one X and one Y.

Sharon Moalem, the author of The Better Half: On the Genetic Superiority of Women, says that means women have a more aggressive immune response than men, whose system takes more prodding "to get off the immunological couch."

Women's immune systems also have more resources to call on and can cooperate across the chromosomes.

"If a female has an immune cell that's using the X from her father and that has genes on it that can recognize COVID," Moalem said in a BBC programme this week, "whereas the other immune cells using the X from the mother are very good at killing COVID, working together...that's why the female has that leg up when it comes to survival."

Researchers may be trying to unlock the puzzle of higher death rates for many years to come, but it's not unique to COVID-19. It has been seen in other coronavirus epidemics – the 2003 SARS and the 2012 MERS outbreaks.

However, Ian Hall, a professor of molecular medicine at Nottingham University, says he suspects COVID-19 is slightly different and the way it works may provide a clue to how to deal with it.

He explained that after a protein on the virus binds to a receptor on the lung cell, it enters the cell and goes through a process that allows the virus to replicate itself. This, in turn, produces an inflammatory response in the lung, which may be subtly different between men and women.

"If you could identify the reason why this may be regulated differently in men and women that could give you a route into treatment," he tells CGTN Europe.

Hall believes there's probably enough data available to get to grips with the issue, but it's striking how few governments provide a gender breakdown of cases and deaths.

Nearly three-quarters of healthcare workers around the world are female. /AP/Petr David Josek

Nearly three-quarters of healthcare workers around the world are female. /AP/Petr David Josek

That has drawn attention to some often overlooked questions: How do epidemics more broadly affect men and women differently and why don't governments publish more figures on it?

It is estimated that 70 percent of health workers in the world – those often most potentially exposed to the virus – are women. Women are often domestic caregivers and can be differently affected by quarantine measures.

Yet Clare Wenham, assistant professor in global health policy at the London School of Economics, says there has been no analysis of the gender effects of COVID-19, either during preparations or since the outbreak started.

Even though, for example, the sex of victims will be recorded on death certificates, surprisingly few countries actually publish the data.

"We know it's being collected," she tells CGTN Europe. "Maybe governments don't care about women."

Adding: "They need to publish data, make it accessible and look at the broader policy implications. We live in hope."

In other words, the reasons why men are dying from COVID-19 in disproportionate numbers may still be a mystery, but providing the data to help solve it may help us understand some of the wider impacts of the pandemic.