01:37

Europe's 2015 refugee crisis made one thing clear: Africa's problems are not the continent's alone. So in its wake, Germany created the 'Compact with Africa' during its presidency of the G20 in 2017.

The basic idea was that if development aid was not enough to bring stability to a region that has lacked it for so long, perhaps the private sector could supplement those efforts. Governments from 12 African countries would work with G20 business leaders to create a more investment-friendly environment.

And once domestic reforms were implemented to make that a reality, so the argument went, the money would begin to flow. Jobs would be created, the economy would grow.

That would bring stability, and in doing so reduce the need for large numbers of people to flee to Europe. More than two years on, that has not yet fully materialized. Indeed, while foreign investment into participating countries increased last year compared with the previous one, it remains lower than it was in 2016.

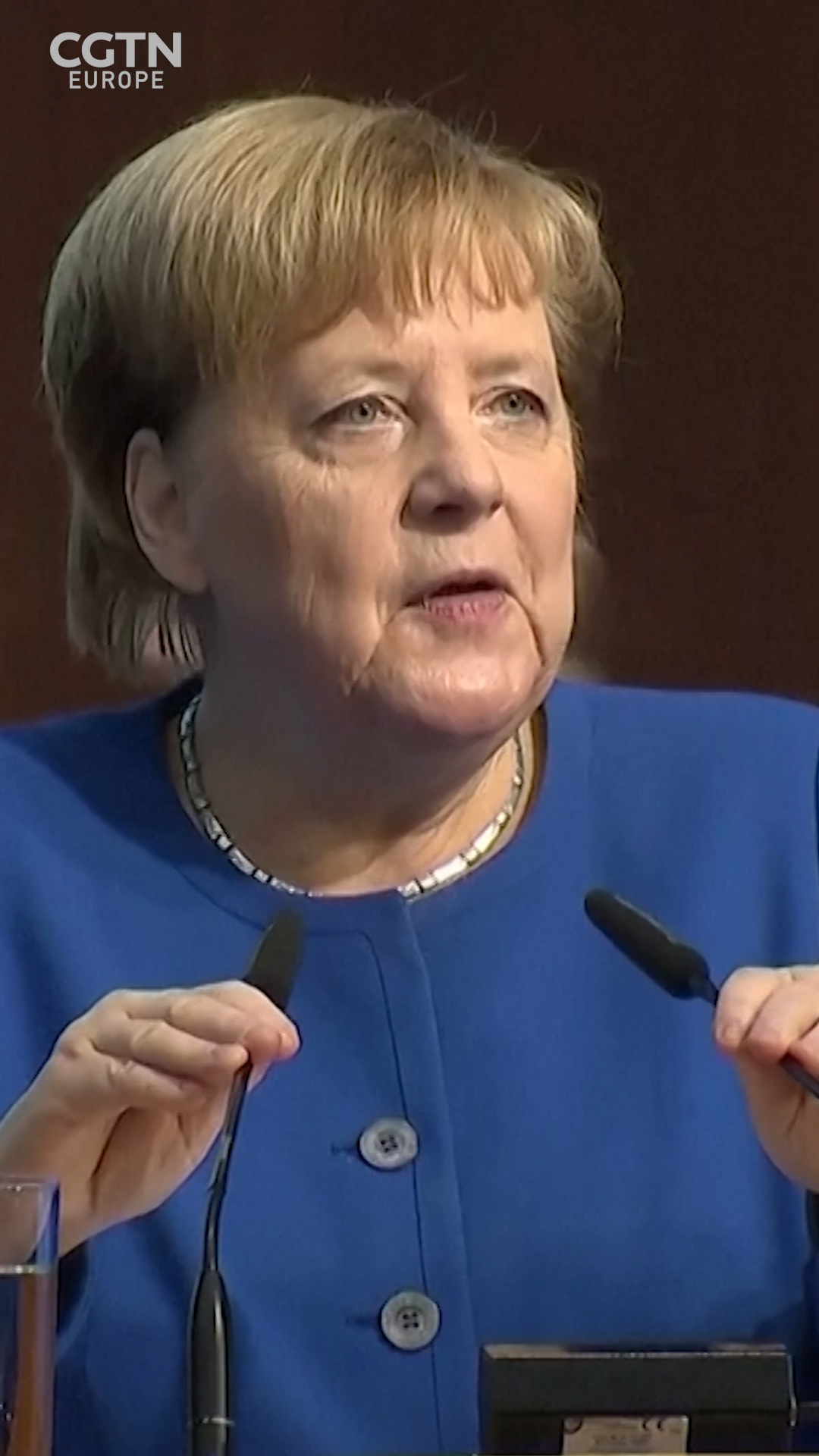

German Chancellor Angela Merkel with Egypt's President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi (left) and Rwanda's President Paul Kagame (right) (Credit: AFP/ John Macdougall)

German Chancellor Angela Merkel with Egypt's President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi (left) and Rwanda's President Paul Kagame (right) (Credit: AFP/ John Macdougall)

The German capital is swarming with convoys of blacked-out cars in heavily-protected police convoys this week, as it plays host to the Compact with Africa Conference with numerous bilateral meetings at the German Chancellery on the side.

At an investment summit in front of many of the visiting delegations on 19 November, Chancellor Angela Merkel gave her explanation for the slow start: participating countries should do more to re-assure investors that their money will be safe in a region traditionally seen as a risky bet, particularly when it comes to transparency.

Some African governments may feel they have already taken advice that has not yet fulfilled its promises.

Ultimately, the aim of this plan is to bring stability to places that do not have enough of it. But that is a hard foundation to build private sector investment off.

At one end of the spectrum, the continent's two largest economies – South Africa and Nigeria – were not included. On the other hand, neither were violence-wracked Mali or Central African Republic.

Does the mix of countries get near enough to the heart of the problem, without putting off investors so much so as to doom the whole initiative to failure? Minnows Burkino Faso and Guinea are beneficiaries, for example, while so are larger economies Ghana and Egypt.

There is much at stake for the host country and its chancellor, who led Europe through the 2015 refugee crisis but not entirely out of it. The continent remains ill-prepared for another influx, and yet is still an island of relative stability surrounded by a sea of chaos from Aleppo to Tripoli.

If the Compact With Africa was partly designed to tackle the migration issue at source by preventing people leaving, the apparent lack of progress must be a worry not just for its participants but for the whole of Europe.